National Judicial Policy: A concept note and ten visions for 2030

This draft for consultation argues for the need for a national judicial policy and identifies ten visions to transition the Indian judiciary into a litigant centric one by 2030

Draft for consultation

This paper draws on the JALDI team’s years of research on judicial reforms, to identify some critical and all pervasive issues that woe the judiciary. While they are, in some form, a culmination of our past research, this document is by no means the finish line of the journey. Instead, it aims to be a conversation starter for the judiciary to address its challenges and plan its future in a renewed way. We hope that this consultation paper brings people from the ecosystem together with experts from various other disciplines to deliberate on how the judiciary can achieve the ten visions and transform into a litigant centric institution by 2030. Drawing on the consultations, in the upcoming year, there will be follow up publications which go deeper into each of the visions along with a tentative roadmap towards realising them.

Need for a national judicial policy

Pre-independence, the Indian judiciary was designed to subserve colonial interests and not to cater to the needs of the governed. Its origins can be traced back to the Charter of 1726 and to the Government of India Act of 1935 which went on to lay down the foundation of the Constitution of India in 1950. Today, many years after independence, the remnants of its colonial roots can be seen in a plethora of avenues ranging from dated laws, to inefficient administrative machinery and even non-inclusive physical infrastructure. For the Indian judiciary to transition into becoming responsive to the contemporary needs of the litigants, there is a need for the judiciary to make a comprehensive assessment of all its issues and introduce a mechanism for holistic planning. For more details see pg. 4.

Presently, for those issues that fall within the purview of the judiciary, changes come through piecemeal interventions selectively chosen by the Chief Justices of the Supreme Court and High Courts. Quite often their recommended introductions expire with their tenures. Institutionally, there are no mechanisms to ensure long term continuity of policy measures. In the same vein, other changes come through ad hoc committees, which seldom engage with experts and often set up to address piecemeal problems and not the underlying structural issues. To remedy this, there is a need for a mechanism which identifies structural problems that thread between the issues faced by the judiciary and introduce a comprehensive plan, which can address these issues, in an organised manner over the years. This for the judiciary can come in the form of a National Judicial Policy. For more details see pgs. 1-2.

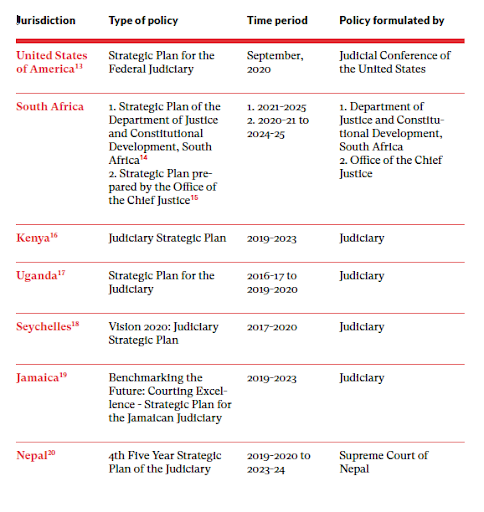

International precedents for long term vision driven policy making

Long term vision driven policy making is not a new phenomenon. Forward thinking policy making has been informing reform on complex subjects both nationally and internationally. In India, examples range from the National Education Policy released by the Ministry of Human Resource Development in 2020 to the documents released by the NITI Aayog such as the three-year action agenda in 2017 to the Strategy for New India@75 in 2018. Internationally, such strategic policy making has been adopted by judiciaries as well. The table below identifies some of these efforts. For more details see pgs. 3-4 of the report.

Transitioning to a litigant centric judiciary

To determine what ought to constitute this comprehensive policy, a determination of the core principles of the judiciary is essential. The report identifies six principles that are essential to a good justice system and should form an integral part of how the judiciary envisions itself. For more details see pg. 5

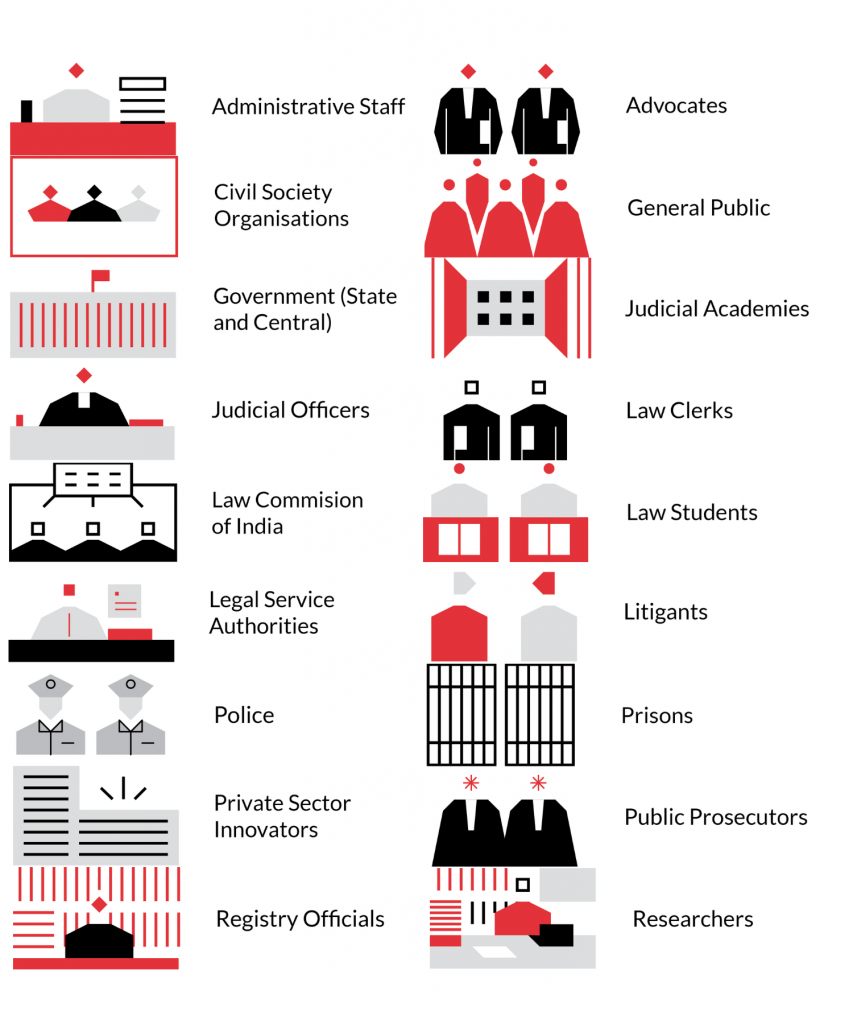

Another key aspect which needs to inform policy making is an assessment of who the policy will benefit and which actors will play a key role in implementing the vision. Therefore, the report identifies some of these stakeholders. While the universe of these actors can be infinite, the present list only maps out first degree stakeholders. For more details see pgs 5-6.

The ten visions for 2030

After centering these principles and the stakeholders, the report identifies ten visions for the judiciary for the year 2030 i.e. Vision 2030. These visions are preceded with some context on why the judiciary is in need of reform for that specific sphere and hopes to provide a compelling case for prioritising this vision. The context is followed by more specific vision components which identify targeted actions i.e. form sub-parts to the larger vision. Finally, the text identifies the stakeholders who will play a key role along with the key principles that the vision evokes. Since these visions draw on the extensive work done by JALDI over the years, our prior publications, along with other seminal research on the subject have been cited.

For quick reference, our research is also identified below.

Vision 1: The Indian Judiciary must have modernized and accessible infrastructure

Read more on Pg. 10.

Referenced work

Report: Re-imagining Consumer Forums: Introducing a spatial design approach to court infrastructure

Report: Building Better Courts: A survey of physical, digital and human infrastructure of 665 district courts in India

Interactive portal: Building Better Courts Surveying the Infrastructure of District Courts

Opinion: 70 Years Of Indian Judiciary: Our Courts Need To Be More Welcoming, Accessible, Purpose Driven

Vision 2: The Indian Judiciary must have an efficient administrative machinery

Read more on Pg 14.

Vision 3: The Indian Judiciary must fully utilize its judicial capacity

Read more on Pg 18.

Referenced work

Report: Back to Basics: A Call for Better Planning in the Judiciary

Interactive portal: The JALDI Portal on Judicial Vacancies in India

Report: The Delhi High Court Roster Review: A Step Towards Judicial Performance Evaluation

Vision 4: The Indian Judiciary must have better engagement with stakeholders and mechanisms to assess progress

Read more on Pg 22.

Referenced work

Report: Back to Basics: A Call for Better Planning in the Judiciary

Interactive portal: Budgeting for Better Courts

Vision 5: The Indian Judiciary must have mechanisms to promote diversity and heterogeneity

Read more on Pg 26.

Referenced work

Report: Tilting the Scale: Gender Imbalance in the Lower Judiciary

Journal publication: The Rise of Women in the Lower Judiciary: Breaking through the Old Boys’ Club

Journal publication: Absence of Diversity in the Higher Judiciary

Interactive portals: Women in the Judiciary and Gender Diversity

Vision 6: The Indian Judiciary must protect and promote independence

Read more on Pg 30.

Referenced Work

Report: Budgeting Better for Courts- An evaluation of the Rs. 7460 crores released under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme for Judicial Infrastructure

Journal publication: Four Transfers and One Saving Grace

Opinion: Why Judges Deserve a Salary Hike

Opinion: After the judges retire: Time for a fresh look at sensitive judicial afternoons and evenings

Vision 7: The Indian Judiciary must have accountability frameworks to monitor all stakeholders

Read more on Pg 34.

Referenced Work

Report: A Survey of Advocates Practicing Before the High Courts

Opinion: Why Do Lawyers Enjoy Immunity Against Wrong Practices?

Opinion: Examining the Special Prosecution Needs of Criminal Justice

Vision 8: The Indian Judiciary must uphold the ideals of an open judiciary

Read more on Pg 38.

Referenced Work

Report: Sunshine in the Courts – Ranking the High Courts on their Compliance with the RTI Act

Interactive portal: RTI Templates for High Courts

Report: Open Courts in the Digital Age: A Prescription for an Open Data Policy

Vision 9: The Indian Judiciary must have a robust framework for judicial education and training

Read more on Pg 42.

Referenced Work

Report: Schooling the Judges: The Selection and Training of Civil Judges and Judicial Magistrates

Vision 10: The Indian Judiciary must be driven by a humane, reformative and rights-oriented justice system

Read more on Page 46.

Referenced Work

Report: From Addict to Convict