The Delhi High Court Roster Review: A Step Towards Judicial Performance Evaluation

Evaluation of the Delhi High Court’s performance in 2018 and limitations in conducting such an evaluation.

Summary: The report evaluates the performance of the Delhi High Court as an institution, the performance of its individual judges, and identifies why such a study is difficult to undertake.

Differing Standards for Performance Evaluations

Unlike High Court judges, District Court judges are evaluated throughout the course of their tenure. For instance, they are evaluated through ‘Annual Confidential Reports’ (ACRs) which use a unit-based system to assess qualitative and quantitative metrics. There has also been a discussion regarding the creation of a ‘District Court Monitoring System’ (DCMS), which will draw its data from the e-courts system to monitor the daily performance of district judges in real-time. Further, the eCourts Project has also introduced a JustIS application to help judges evaluate their own performance.

On the other hand, the higher judiciary has resisted similar systems of accountability. For instance, the Judiciary Standards and Accountability Bill, 2010 faced opposition from the bench. Even an external performance evaluation, which ranked judges of the Delhi High Court on grounds such as integrity, understanding of the law, punctuality, was at the receiving end of a criminal contempt notice. As a result, the Editor-In-Chief of the magazine Wah India, Madhu Trehan had to issue an unconditional apology and retract the piece. The rare exception to the general reluctance within the higher judiciary was the self-performance evaluation conducted by Justice G.R. Swaminathan, a sitting judge of the Madras High Court, on completion of two years on the bench.

Difficulties in conducting performance evaluation and limitation of the present study

To conduct a good performance evaluation, comprehensive datasets are essential on various facets of the judiciary. Unfortunately, however, the non-availability of such public databases limit the kind of performance evaluations which can be conducted. First, while the NJDG (National Judicial Data Grid) and the High Court websites do put up some data, they are often on broad-based metrics such as cases disposed and do not tell us about the complexity of the case or the time taken for disposal. Such data is also not published in machine readable formats. Second, given the lack of history of conducting such evaluations, there is a lack of performance standards to conduct such evaluations. Third, there is an absence of qualitative information, survey data and publicly available rationales to assign certain rosters to judges. Instead, they are purely contingent on the discretion of the Chief Justice. It is therefore nearly impossible to assess the strength and weaknesses of the institution and individual judges. For these reasons, even the scope of performance evaluation conducted during this study is very limited. For more details of the limitations of the study please see pgs. 9-10. For more details on how data can be better organised by the High Court to enable performance evaluations please see pgs. 26-28.

Methodology

The current study evaluates the performance of the Delhi High Court for the year 2018 i.e. from January 2018 to 31 December 2018. The data was collected by filing RTI applications and scraping and correlating data from the Lobis tab, the daily orders tab and the pronouncement causelist available on the Delhi High Court website. At various stages, such as while counting the number of cases that were heard, duplicate cases have been eliminated and connected matters have been accounted for. For more details on methodology please see pgs. 30-32.

It is important to note that one of the key metrics studied in this report is the number of pronouncements. This metric was studied as opposed to the number of cases disposed, for two reasons. First, the Delhi High Court website does not, in a consolidated manner, record the number of cases that were disposed by a judge. Instead, judgments are split between the daily orders tab and judgments tab without any particular rationale on why they are so classified. Second, it was believed that cases that were reserved and then pronounced required an additional and significantly higher amount of judicial time and tended to have longer judgments. The reserved judgements were on average 23.89 pages long. On the other hand, the non-reserved judgements were, on average, 7.4 pages long. While there are limitations in assessing judgements based on the number of pages, it can be inferred that, on average, reserved judgements require greater deliberation. For more details regarding this aspect of the methodology please see pg. 21.

Results of the performance evaluation

First, the study analysed the organisation of the roster at the Delhi High Court. The duty to organise such a roster befalls on the Chief Justice, who as the Master of the Roster allocates cases to the various judges. However, there does not seem to be an evident or transparent rationale as to why such allocation takes place. At the Delhi High Court the judges are split between the criminal roster of single judges and division benches, the civil original and appellate roster for single benches, the civil appellate roster for division benches and the writ roster for single judges and division benches. For more details on the kinds of cases and the number of cases covered under these rosters, please see pgs. 11-14.

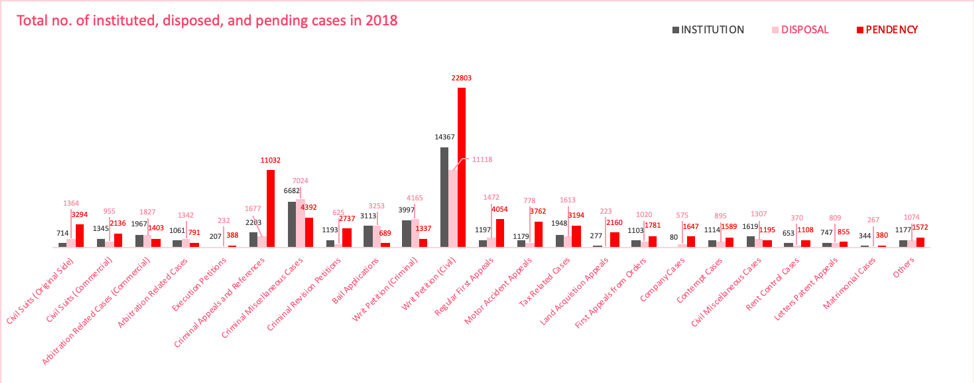

Second, the study conducted an institutional overview of the workload of the Delhi High Court.

The results found that some classes of cases, such as writ petitions and criminal miscellaneous cases were being disposed in comparison to other cases that required more judicial time, such as criminal appeals or original suits. This is unfortunate given that these appeals concern themselves with critical rights and liberties of individuals. On the other hand, writ petitions, for example, are of a discretionary nature and through practice have expanded to include cases that might not need to be addressed with urgency. Analysis of the pronouncement causelist also found similar trends. The possible adoption of the case flow management rules which have been recommended by the Law Commission and the realistic amendment of timelines might provide a more organised, rational and transparent method for the organisation of the roster. For more details on the institutional evaluation please see pgs. 15-20.

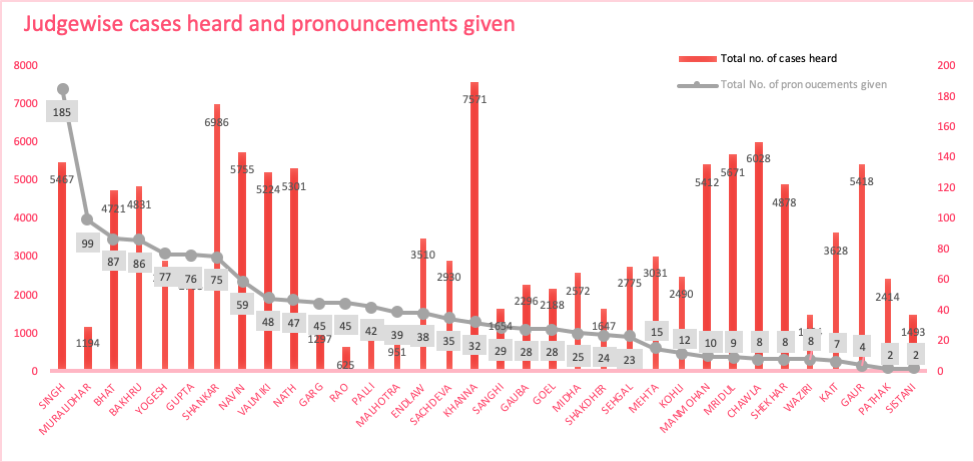

Third, the study analysed the individual performances of judges of the High Court by studying the number of cases pronounced by them. The results of the study found that, in 2018, out of the 34 judges who held court throughout the whole year, some judges performed better than other judges. The data in the chart below compares two metrics – the number of cases heard and the number of unique judgments pronounced by the judges.

The results suggest that judges that heard a large number of cases did not always pronounce more judgments. There are a few plausible reasons for this. First, this could be because judges simply did not devote enough time to author judgments. Second, some judges might not have reserved and pronounced judgments but instead dictated them in court and therefore featured them as daily orders or on the judgments tab of the website, without any pronouncement. Third, given some judges’ management of their rosters, they could have been more inclined to resolve cases through interim orders as opposed to final disposals. Fourth, and most notably, the variance in the number of cases could be on account of their roster allocation. Judges that heard bail applications are more likely to hear more cases as opposed to judges hearing criminal appeals which require greater deliberation. Such a situation is likely to have occured due to an unequal roster allocation or because some judges were choosing to resolve cases that were simpler or more complex than others. For more details on the individual evaluation of judges please see pgs. 21-25.

Way forward

Overall performance evaluations can increase transparency of an otherwise seemingly opaque judiciary. They can also make judges more accountable to the public and identify the poor performing judges, bottlenecks and scope for improvement. At an institutional level, performance evaluation can help increase transparency, and provide insights into how rosters are organised. They can also help identify trends and deduce explanations on why some cases are afforded greater urgency than others. Eventually, one can be hopeful that these evaluations will better inform how judges in the higher judiciary are appointed and promoted.