Sikkim’s Alternative Model to Tackle Drug Abuse: An Analysis of the Sikkim Anti-Drugs Act, 2006

How a health-based approach to drug abuse has ushered a positive change in Sikkim

Context – Sikkim’s unique drug abuse problem

Sikkim has been struggling with alcohol and drug abuse since the 1980s. Illicit use of pharmaceutical drugs stands at the core of Sikkim’s drug problem, which has been gripped by rampant misuse of prescription drugs like Nitrosun, cough syrups and Spasmo Proxyvon.

Enactment of the Sikkim Anti-Drugs Act (SADA), 2006

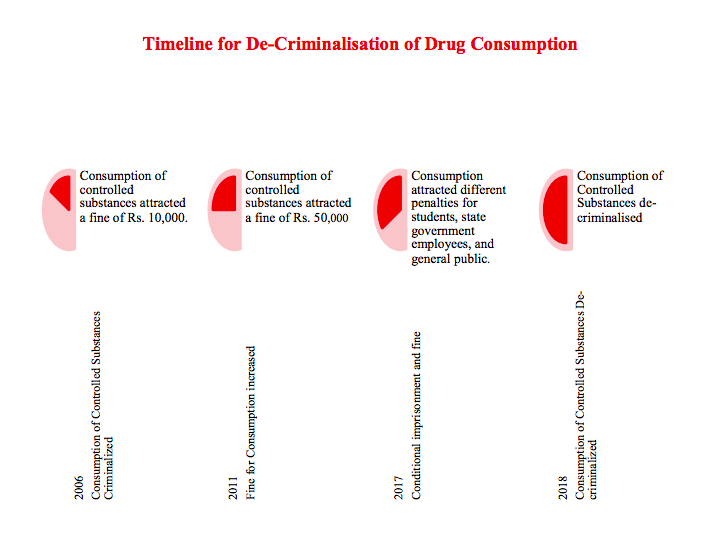

As Sikkim’s drug problem worsened leading up to the early 2000s, it enacted the Sikkim Anti-Drugs Act, 2006 (SADA), with an intent to tackle its own distinctive problems with prescription drug use. SADA was enacted to deal with increasing abuse of medicinal preparations and its provisions mirrored those of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS Act). It continued to operate within a purely deterrence-based model through criminalising illicit drug use.

Amendments to SADA in 2011 calling for stricter punishments

Interestingly, SADA did not provide for imprisonment for illicit drug use and limited the penalty to a fine of Rs. 10,000. However, in 2011 SADA was amended to provide for stricter punishments and the fine for illicit drug use was increased from Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 50,000.

This prompted sustained advocacy by the Sikkimese civil society, which drew attention to the futility of tackling addiction through criminalisation. Amendments to SADA that followed reflected an altered state policy towards drug use.

An altered approach – 2017 amendment to SADA

- Differentiating between peddlers & consumers: In 2017, SADA was amended to recognise the distinction between ‘peddlers’ and ‘consumers’. Anybody caught with small quantities of drugs was now categorised as a ‘consumer’ while those caught with larger quantities were categorised as ‘peddlers’. The recognition of this distinction enabled SADA to channelise Sikkim’s healthcare services to the most vulnerable drug users.

- Adopting a rehabilitative approach: Additionally, the amendment changed the scheme of punishments and rehabilitation, which now treated illicit drug users differently from sellers, manufacturers etc. The law made psychiatric evaluation of all illicit drug users compulsory, while detoxification and rehabilitation was also provided for, if necessary.

- Novel method for determining drug quantities: The amendment also provided for a novel quantification method. Unlike the NDPS Act, where small and commercial quantities were provided against all drugs in weight and volume, SADA used three delivery formats (tablets, syrups and injection vials) to determine quantities, thus avoiding inconsistencies arising out of measurement in weight and volume, often when prohibited substances are found in the form of pills or syrups.

2018 amendment and decriminalisation of illicit drug use

In 2018, SADA went a step ahead in its altered approach to drug use and decriminalised illicit drug use. It also laid down elaborate provisions for detoxification and rehabilitation.

Highlights of the 2018 Amendment

Decriminalisation of drug use: While drug use was earlier classified as a contravention under SADA along with manufacturing, transporting etc., the 2018 amendment removed ‘use’ from the list of contraventions. As SADA discarded criminal or administrative penalties for drug use, it forged ahead of many foreign jurisdictions, where illicit drug use has been decriminalised but continues to attract administrative penalties such as fines.

Detoxification and rehabilitation: SADA created an inclusive system that facilitated access to healthcare services for all small quantity offenders and addicts, entitling them to psychiatric evaluation followed by detoxification and rehabilitation, as required. This ensured that persons who engaged in small scale peddling to support their addiction were not excluded from the benefits of detoxification and rehabilitation.

Importantly, SADA did not force compulsory detoxification and rehabilitation, recognising that involuntary and forced deaddiction could do more harm than good. Studies abroad have linked involuntary drug treatment to drug overdose and human rights abuses within compulsory treatment settings.

Impact of the amended SADA on the ground

Sustained advocacy by doctors, de-addiction centres and other members of the civil society had an indelible impact on the writing of the law and the changes in the law in turn impacted how people perceived drug use and addiction in the state.

Removing stigma: Decriminalising drug use removed the stigma that comes inherently with the criminalisation of any activity. Since drug use was no longer a criminal offence, the police instead of registering cases and arresting drug users, ascertained the need for de-addiction and facilitated rehabilitation.

Partnership based approach for rehabilitation: On apprehending any drug user, the police immediately informed a registered de-addiction centre, who then interacted with the user and assessed the need for institutionalisation. The user’s family was consulted and the drug user was dealt with according to his/her specific needs. The focus of law enforcement agencies shifted to large scale peddlers while all drug addicts had access to healthcare and rehabilitation facilities.

In conclusion – lessons for all

Although a small section of the Sikkimese civil society pushed for decriminalisation of drug use, the government was receptive to the idea. Exemplary coordination between various departments of the state government exhibited a common resolve to address the issue of drug abuse. This is evident from the falling numbers of arrests and incarcerations in Sikkim in 2019. While no official data on this was available, interviews with police and prison authorities revealed that undertrials in the Sikkim Central Jail had fallen from over two hundred to a mere sixty-six after the 2018 amendment.

The state government has also devised a range of state run programmes that facilitate SADA in achieving its ends. These include the State Action Plan for Drug Demand Reduction (SAPDDR) and the Sikkim Against Addiction Towards a Healthy India (SAATHI) initiative, among others. These programmes use awareness drives and peer education to tackle drug addiction, and represent an important effort in creating a law that places the individual at the core of drug law reform.

The Sikkim state government’s approach and efforts hold lessons that can be replicated at the national scale, particularly in light of the findings of the recently released study on drug use in Mumbai by Vidhi, which demonstrates how the enforcement of the NDPS Act disproportionately targets the most economically and socially vulnerable people while letting off the traffickers.

With only 12% of all drug dependent people receiving help or treatment across the country, SADA can act as a model law that seeks to bring drug use under control by encouraging drug dependent people to approach healthcare services without any fear of prosecution and imprisonment.

Read Vidhi’s August 2020 report: A Case for Decriminalising Cannabis Use in India.