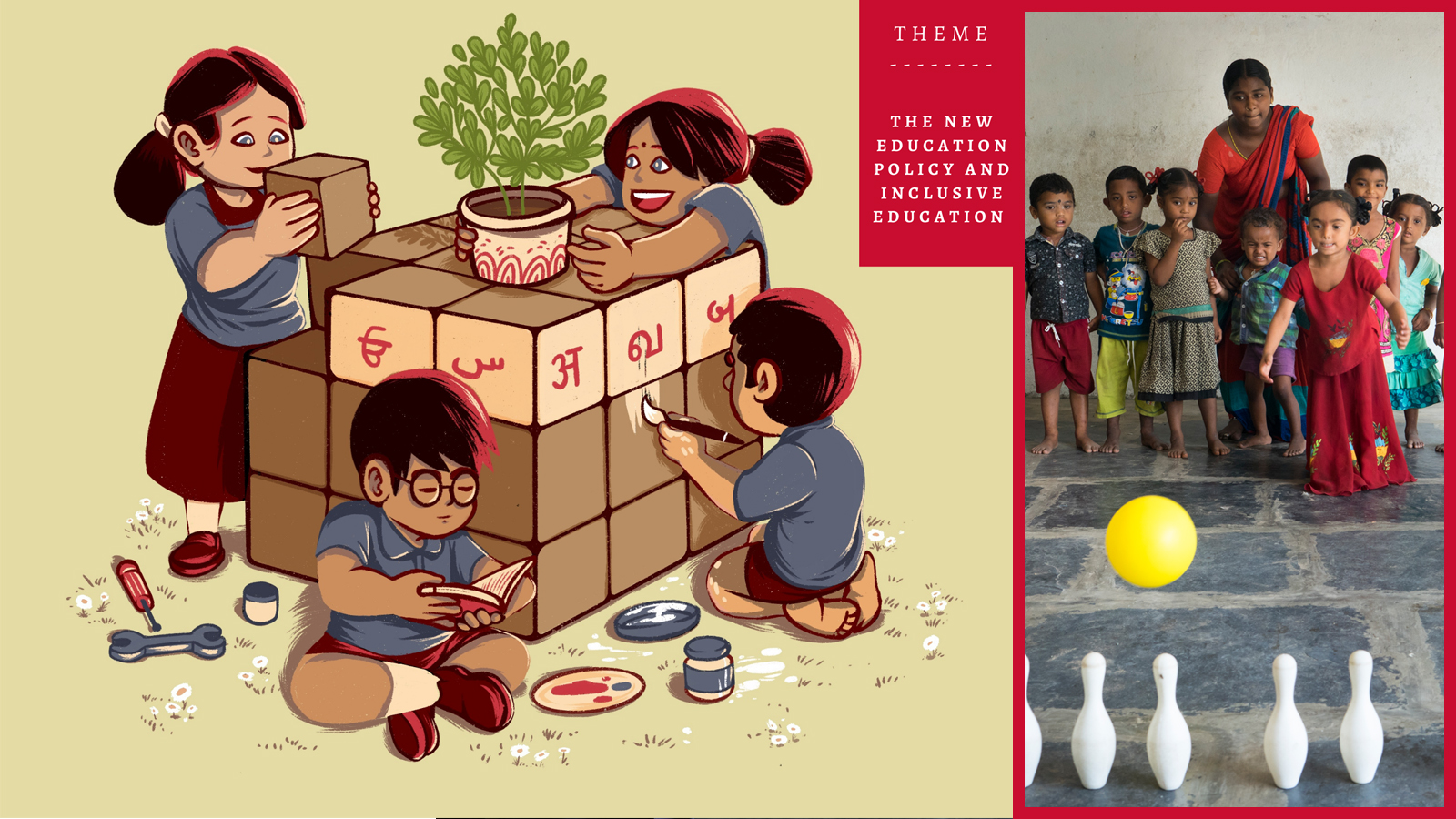

The New Education Policy and Inclusive Education Framework in India

Part one of a three-part series on the National Education Policy: A historical overview of how inclusion has been viewed in different national education policies

Inclusion, Equity and the National Education Policies (NEP)

One of the biggest highlights of this year has been the launch of the much awaited National Education Policy which came about after an excruciating wait of over three decades. Of the many things that have captured public attention, one theme has been the idea of inclusion and equity. In all education policies throughout the years, the idea of Inclusive Education has often revolved around making education accessible and available for all, and especially for children from marginalised milieus. While the overarching idea remains more or less the same, each policy document offers a different narration of which categories of learners require support in inclusive education and deserve more attention. This article provides an overview on how different ideas and manifestations of Inclusive Education have found their place in NEPs historically.

Historical Leanings of Inclusive Education and its Sub Categories

The life cycle of the National Education Policies can be traced back from 1968, 1986 and finally to the most recent policy of 2020. In any policy document, words matter. The NEP 1986 has meticulously and neatly divided the focus of inclusive education into different categories of marginalised populations and dedicated separate sections on their issues (which was one of the critiques of the 1986 policy). The focus of the time was primarily on ensuring universal access to, and providing quality education to a wide base of learners. What was however, strikingly unique about NEP 1986 was its insistence of many nuanced categories of marginalisation. It accounted not just for the traditional marginalised categories but also the relatively newer and less discussed categories like working children (focus on them was mainly through non-formal schooling though), children from economically poor urban slum communities; migrant children; children of construction workers and agricultural labourers; children from forest dwelling communities in remote areas; children from ecologically deprived areas etc (NEP 1986- Section 7).

Despite nuances in the document, implementation strategies did not fully account for these variations and missed out on important categories such as ‘children in conflict with law’ and ‘children in need of care and protection’.

Another critique of the NEP 1986 was that it walked on a tightrope of mentioning a number of encouraging ideas but never backed it up with a corresponding legal framework, policy or implementation programme. For instance, it mentioned assimilation of children with special needs and girls into education but never had any dedicated financial, programmatic or institutional structure to drive it further.

The NEP 2020 on the other hand, has moved away from the traditional categorisation of the marginalised and to some extent has recognised the interconnectedness and multidimensionality of these sites of exclusion. The policy makers have moved beyond the simplistic understanding of boxing these categories individually and taken crucial intersectionalities into account by putting them into the broader category of Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Groups (SEDGs). This exhibits an important departure from the previous trends. However, there is always a risk of subjectivity in interpreting who constitutes SEDGs. This dilemma might particularly be faced during implementation with the brunt of such subjectivity being disproportionately borne by the group of learners who did not find recognition in either NEP 1986 or NEP 2020. Such examples include categories like students from the LGBTQI communities, refugee children, internally displaced communities, children in conflict with law and many more. In another important departure from the previous trends, NEP 2020 has not given any explicit recognition to caste-based inclusion and reservations (neither for learners nor for the teachers).

On the bright side, the NEP 2020 is willing to deploy a greater focus to issues of gender parity through inclusion of transgender children and the “gender inclusion fund”. The constitution of Special Education Zones (to be established specifically in disadvantaged regions across the country with the objective of providing targeted attention to students and teachers in these zones and ensure joint monitoring by both Centre and the states); flexibility and recognition given to school models such as madarsas, gurukal etc. and the standardization of Indian Sign Language (ISL) are a welcome move and furthers the cause of inclusion.

NEP’s section on School education is also particularly reassuring for many. The insistence on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), flexibility in assessments, more robust and inclusive learning outcomes, well rounded education and prominence given to teacher training are some of the few things worth watching out for during the implementation phase.

Views are personal. This article first appeared in the ‘Excerpts from the Expert Series’ of the RGNUL Student Research Review (RSRR). The full article can be accessed here. Read part two and part three of the series on the National Education Policy.