Penalising Before Providing

A study of enforcement of COVID-19 related norms in Delhi

Introduction

As the novel coronavirus (‘COVID-19’) began to spread across the globe in early 2020, a momentous effort was made by governments and international organisations to appraise people of the dangers associated with it. This was accompanied by strict curbs on public gatherings and movement.

India’s initial response seemed cautious and calculated but changed dramatically as more cases were reported. To contain the spread of COVID-19, a nationwide lockdown was announced on March 24, 2020. To enforce the lockdown, law enforcement agencies were armed with penal provisions of the Epidemic Disease Act, 1897 (‘ED Act’), the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (‘DM Act’) and the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (‘IPC’).

Lockdown violations and non-observance of COVID-19 appropriate behaviour (‘CAB’) were categorised as criminal offences. Not wearing a mask, not following quarantine and isolation guidelines or not maintaining social distancing could get people arrested and sentenced to imprisonment. In June 2020, the Delhi Government also empowered the police and other officials to impose fines for violations on the spot.

To understand how criminal laws were used to ensure compliance with COVID-19 containment measures in the National Capital Territory of Delhi (‘Delhi’), we assessed the provisions invoked and the processes involved. To understand the role played by police and courts in the enforcement of these measures, we evaluated First Information Reports (‘FIR’) and orders passed by Magistrate courts. To further understand whether criminal sanctions could ever guide public behaviour, particularly in absence of supportive measures from the government, we conducted a survey to document the public perception around the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Findings

Policing

As per the Government’s order, fines were envisaged as the primary punitive sanctions and First Information Reports (‘FIR’) were to be filed only in case of failure to pay the fine. Still, from March 2020 to March 2022, 23,094 FIRs were filed and 54,919 persons were arrested under Section 188 of IPC, provisions of DM Act and ED Act in seven districts of Delhi. Majority of FIRs were filed for not wearing a mask.

| South-West | West | Central | New Delhi | Dwarka | North | North-West | |

| FIRs | 4029 | 6248 | 2762 | 796 | 3405 | 3756 | 2098 |

| Persons Arrested | 40119 | 6271 | 3845 | 1083 | 3601 | N/A | N/A |

The Government sought to ensure deterrence through punishment by setting daily targets for fines – as high as Rs. 2000, to be imposed. As a result, from March 2020 to March 2022, over Rs. 59 crores were collected as fine by the police in nine districts and by their metro, airport, traffic and railway wings. Over Rs. 32 crores were collected by other authorities in eight districts.

While the police believed that fines acted as a deterrent and that people were more scared of the fine than the disease, they also conceded to the fact that orders regarding fines were difficult to impose as people had no money. Our interviews with the police also revealed that many people preferred having an FIR registered instead of paying the fine on the spot, as it was excessive and unaffordable.

As making people experience fear became central to policing, and with no material evidence of the deterrent effect of punishments, it seems that the only tangible effect was the criminalisation of the most marginalised sections of society.

Adjudication by Courts and Sentencing

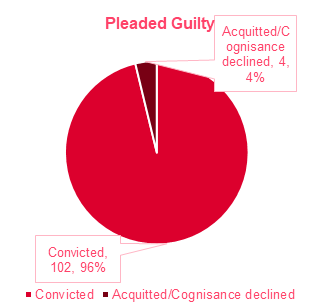

Of the 110 cases analysed, the accused pleaded ‘guilty’ in 106 cases. 102 such cases led to a conviction. None of the ‘not guilty’ pleas led to a conviction.

Out of the 44 orders analysed, all 37 conviction orders are short and barely discuss the necessary procedural and evidentiary requirements. In contrast, the acquittal orders flagged substantial issues with the prosecutions.

In one acquittal order, the court highlighted the absence of a complaint under section 195 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and proof of knowledge of the order of the public servant which is essential to prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt. This strict scrutiny by courts is only visible in 4% of the cases.

Our data also shows that courts also ordered widely different punishments. In cases where the orders were available, the accused were fined in 26 cases and admonished in 14 cases. For not wearing a mask, one court imposed a fine of Rs.4400, while another ordered a fine of only Rs. 50. The judgments do not indicate which principles were used to arrive at these figures.

| Court | Minimum Fine (in Rs.) | Maximum Fine (in Rs.) |

| Karkardooma | 0 – Accused admonished | 200 |

| Tis Hazari | 100 | 200 |

| Patiala House | 100 | 100 |

| Saket | 1000 | 4400 |

| Dwarka | 0 – Accused Admonished | 0 |

| Rohini | 0 – Accused Admonished | 0 |

Lessons from the Pandemic

The challenges thrown by the COVID-19 pandemic were unprecedented and there was no ‘perfect’ response to the crisis. Even then, placing criminal law at the centre of the state response, manifested misplaced priorities.

While the state believed that using criminal law was important because people were not sufficiently scared of infection to follow CAB, interviews with Delhi residents suggest otherwise. Of the 330 residents we interviewed, 300 responded that they followed CAB because they were scared of COVID-19 rather than the police.

Our interviews with police personnel also revealed that apart from enforcing the COVID-19 containment measures, they were tasked with other ancillary tasks such as the distribution of essentials and carrying out awareness campaigns. All of this with little guidance from the government made the system chaotic. While decreasing reliance on criminal law could have relieved some burden on police officers, increased participation of other departments and a coordinated response could have helped in better handling of the lockdown.

Further, instead of using criminal law to force people into compliance, the government could have encouraged voluntary compliance by providing people with vital information about the virus, essential resources and support. Of the 330 respondents we surveyed, 104 said that they were not aware of any social support services made available by the government. 112 said that they were not aware of any financial aid schemes of the government during the pandemic.

In future, such emergencies must be encountered with carefully designed mechanisms that are feasible, proportionate and do not penalise people for the executive’s failures.