Using Compulsory Licensing to Address the Vaccine Shortage

India must invoke available legal clauses to prioritise public health over patent rights

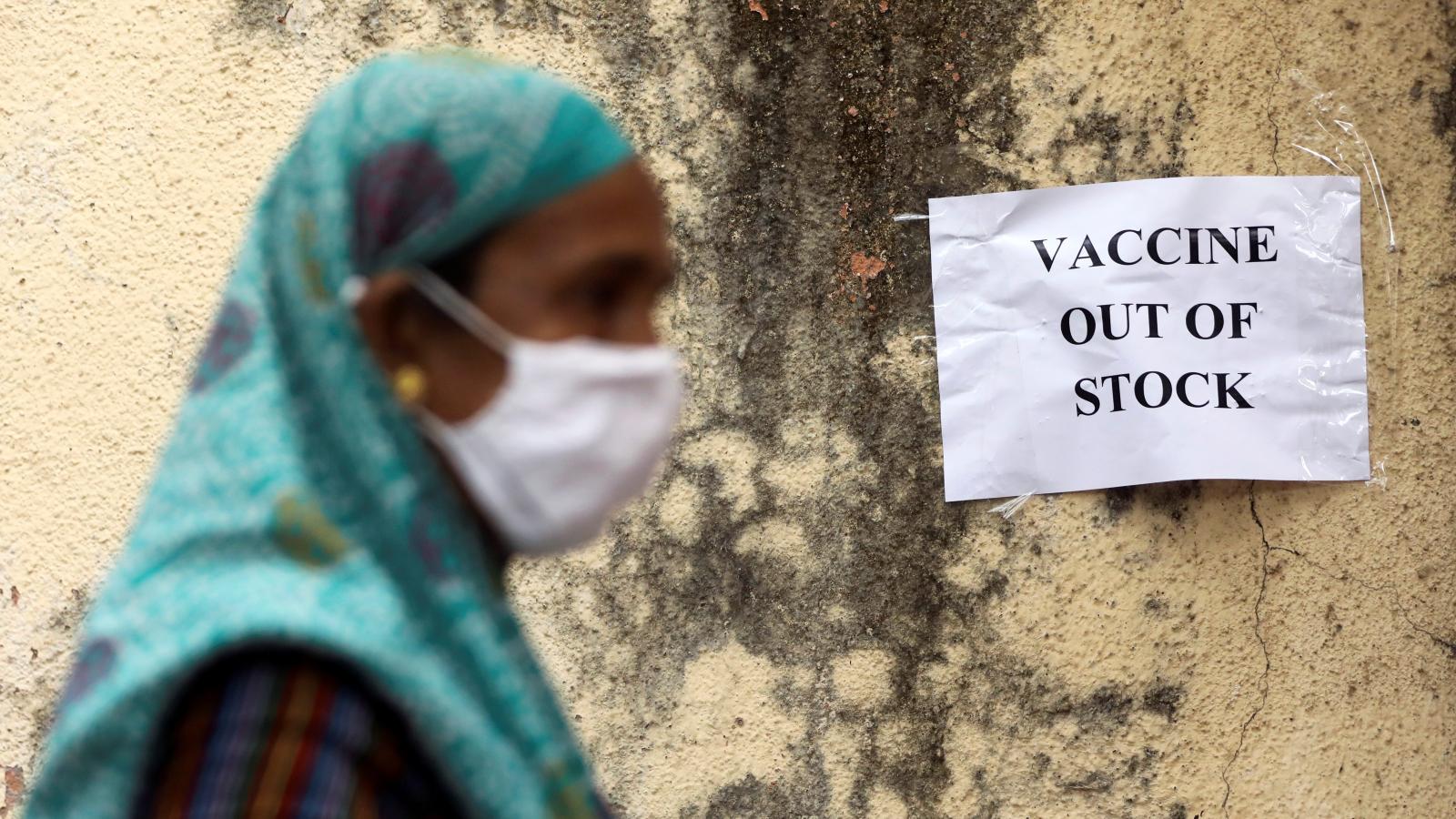

India is facing a critical shortage of key medical drugs and equipment as an ongoing second wave of COVID-19 shows no signs of abating. India’s vaccination drive is in shambles with less than 3% of the population fully vaccinated and most states reporting a shortage of stock.

Last week, the Supreme Court of India took cognizance of the matter and provided suggestions to the Central Government regarding the distribution and pricing of vaccines, supply of oxygen to hospitals and production of medicines used to treat COVID-19 symptoms such as Remdesivir, Favipiravir and Tolicizumab.

While the Supreme Court laid emphasis on removing domestic obstacles to the supply and production of such medical supplies, undercurrents of global diplomacy regarding vaccine distribution and access to medicines have also played a role in India’s current health crisis. This blog explains the point further.

What is the TRIPS Agreement?

In international trade law, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement) grants patent protection to all member countries of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Patents are documents issued by countries to inventors of novel and commercially valuable goods such as pharmaceutical drugs, which give them the right to produce their inventions exclusively.

Regardless of the place of invention, inventors are required to seek patents from all countries in which they sell their inventions. Each country has their own legislation to regulate patents. In India, foreign and domestic inventors must apply for an Indian patent under The Patents Act, 1970 (Patents Act).

When foreign inventors of medical supplies such as vaccines and other pharmaceutical drugs receive their patents from India, they can stop other companies in India from manufacturing these supplies without obtaining a licence. These individuals or companies that own the inventions may charge exorbitant licence fees or refuse to license their innovations, preventing affordable and equitable access to health.

Individual countries too are required to protect the rights of these foreign inventors. The TRIPS Agreement is a binding document that provides minimum standards of protection that each country has to provide to patented inventions within their legislations. A violation of the TRIPS Agreement can result in proceedings as per the WTO dispute settlement mechanism.

Why has India asked for a waiver of the TRIPS Agreement?

In October 2020, India and South Africa had submitted a joint communication titled “Waiver from certain provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the prevention, containment and treatment of COVID-19” to the TRIPS Council at the WTO. This waiver of the TRIPS Agreement requested halting of enforcement of patent rights which would allow companies to domestically produce supplies for COVID-19. While it has not been specified whether the waiver will provide compensation to the patent owners, it is a temporary measure that will not result in any one losing their patent and has been requested in the face of a raging pandemic.

Despite receiving considerable support from many developing and under-developed countries, the United States, European Union and other developed countries had initially opposed the waiver. Many pharmaceutical and technological giants hail from these countries, and their patents form a part of their country’s investment and resources. The waiver thus reached a deadlock at the WTO.

Countries that opposed the waiver also stated their intention to aid the distribution of vaccines to developing and under-developed countries through the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access facility (COVAX) or through voluntary licensing agreements at a not-for-profit basis to other companies. They asserted that curbing the pandemic would not need a waiver of the TRIPS Agreement in light of these alternatives. However, this position failed to consider that India had requested a waiver of patent rights on treatment methods and equipment for COVID-19 and not just vaccines. Drugs such as Remdesivir and Tocilizumab are patented or in the process of being patented in many countries and their production is therefore limited to the owner of the patent or select licensed companies. While around seven companies in India have the licence to manufacture Remdesivir, their production is not able to meet the current demand at an affordable cost.

Presently, many countries that had opposed the waiver have stepped in to aid India by sending emergency medical supplies. However, these shipments cannot provide all the items required and will only temporarily ameliorate the situation. The present health crisis or a future one can be wholly addressed only by ensuring that companies within India can manufacture all materials and diagnostic equipment needed.

While, in a significant recent development, the United States has finally agreed to the TRIPS waiver for vaccines, the negotiation for the waiver and the resultant terms and conditions remain to be seen.

Compulsory licensing can ensure access to treatment

Although an international consensus on the temporary waiver of the TRIPS Agreement would have been ideal, India can still consider other beneficial provisions from domestic laws and other international agreements to address its current needs. In several countries, patent laws allow governments to issue compulsory licences. When a country does not have access to a patented invention at affordable rates or the production is insufficient to meet the demand reasonably, the government can compel the owners of patents to license their invention to other companies. This licensing is done for a certain amount of compensation or fixed small royalty as opposed to owners usually licensing the inventions at their preferred rates.

Under international law, the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health in 2001 (Doha Declaration), which supplemented the TRIPS Agreement, mentioned that WTO countries are allowed to determine circumstances and terms for issuing compulsory licences. In India, the Patents Act provides compulsory licensing as one of the powers vested with the Controller General of Patents in India (Controller). The Patents Act states that the Controller must ordinarily wait three years from the grant of a patent before issuing a compulsory license but national health emergencies, like the present pandemic, are an exception to the waiting period. As per section 92 of the Patents Act, the Central Government is required to issue a notification stating that on account of a national health emergency, specific patents can be compulsorily licensed, and subsequently the Controller can issue licences to all applicants that wish to manufacture the product. No such notification has been issued by the Central Government yet.

Additionally, for determining whether production of a patented drug is adequate to meet the public’s demand, an earlier decision by the Bombay High Court had held that in case of medicines, a public’s demand is only met when the drug is available to all the people who require it. To ensure that all people have access to the medicine, the Court had at that time held that the Controller could issue compulsory licences.

Therefore, international agreements and Indian laws, through the Doha Declaration and the Patents Act respectively, provide a scope for compulsory licensing of patented inventions in certain circumstances. An example of compulsory licences requested for COVID-19 related pharmaceutical drugs is Natco Pharma Limited filing an application for waiver of the patent on the rheumatoid arthritis drug Baricitinib before the Controller. In India, this drug is used to prevent an excessive immune response in COVID-19 patients and is patented by a foreign company. Without Natco producing a generic version of the drug, it is too expensive and is only available for approximately 600 patients across the country. Natco has agreed to pay a seven percent royalty from net profits to the patent owner but the Controller and the Government have not yet responded to this application.

Conclusion

Compulsory licensing requires a government to forcibly deprive the patent’s owner of its ability to exercise its legal rights. Due to the extremity of such a measure, India has rarely considered issuing compulsory licences. Moreover, countries such as the United States have often expressed displeasure at the threat of compulsory licensing that their companies face in developing countries which has created some diplomatic and trade pressure not to enact such measures.

This week, the United States has considered a waiver of the TRIPS Agreement only for vaccines. The Central Government must ensure that this includes a waiver on patents for drugs and equipment that are required to combat the pandemic in India. It is anticipated that the waiver will take a few months to negotiate and so, in the interim, the Government can still consider issuing compulsory licences. Russia can serve as an example as it published an ordinance issuing compulsory licences for Remdesivir and all inventions related to its production.

To conclude, the present circumstances are dire enough for India to consider all legislative provisions that can improve supply of items required. In the same Supreme Court hearing last week, Justice Chandrachud passed an Order asking why the Government hadn’t invoked section 92 of the Patents Act for Remdesivir, Tolicizumab and other such drugs. He requested the government to consider issuing compulsory licences to hasten the process of meeting the requirements of the public.

With compulsory licensing now being discussed widely as an alternative to the TRIPS Agreement waiver, the Central Government and the Controller must seriously consider them as an option to address the problem of access to medicines and treatment of COVID-19 in India.