The Success Story of Kaziranga’s Tigers – Unpacking the Dichotomy

Kaziranga National Park which is known for the single largest population of One-Horned Rhinoceros is also home to the single largest population of tigers in North-East India.

The tiger census of 2018 showed the total number of tigers in the entire north eastern region of India as 219, which included 190 tigers in Assam, followed by 29 in Arunachal Pradesh. Even as all other states in its vicinity including West Bengal, Mizoram and Nagaland recorded decreasing numbers to nil in tiger censuses over the years, Assam outshone them each time.The state had just 70 tigers in 2006, and has thus recorded over 250% growth.

This might look like a great conservation success story – which indeed it is – but it might be too early to celebrate the results. The Project Tiger report which recorded an increase in tiger numbers has also warned that the tiger population in the entire North East Hills remain critically vulnerable and needs immediate conservation attention.

This piece delves deeper into the dichotomy basis field work conducted by the Vidhi team as part of a study to track implementation of environmental judgements. The conservation of Kaziranga and its adjoining areas was one of the cases studied.

Tiger density map for north eastern hills and Brahmaputra floodplains. (Source- Status of Tigers in India, 2018)

Kaziranga – the tiger source

As per the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), apart from tigers dispersing from Bhutan and Myanmar, there are two major source populations of tigers in the north eastern India – the Kaziranga landscape comprising the Kaziranga National park along with several other protected areas in Brahmaputra floodplains; and the Pakke landscape which includes Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh and Nameri Tiger Reserve in Assam.

While Pakke has recorded a decline in tiger numbers in 2018, Kaziranga landscape has been successful in maintaining the pace of increase in its tiger population. The Kaziranga National Park along with the Orang National Park (mini Kaziranga National Park) is also known for the highest density of tigers in the north eastern landscape. A few studies even indicate that their density is the highest in the country.

Wild Water Buffaloes in Kaziranga (Photo: Debadityo Sinha/ Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy). Strict monitoring of the park along with good presence of prey animals like wild water buffalo, gaur, eastern swamp deer, sambar deer, hog deer has helped the tigers to thrive in Kaziranga National Park.

The Kaziranga National Park, also a UNESCO World heritage site, was declared a Tiger Reserve in the year 2007. The ecotonal (transition zone between two ecosystems) landscape of Kaziranga is very unique with a wide variety of habitats, which include the dynamic floodplains of river Brahmaputra on the northern boundary & River Diphlu, grasslands as well as hilly forests of Karbi Anglong district on the south.

Importance of maintaining connectivity of ecosystems

As per a Wildlife Institute of India (WII) study in 2014, it was pointed out that intensive agricultural activity in the north of Brahmaputra river has almost wiped out the ecological connectivity between Kaziranga NP and Pakke NP. But the report stressed that Kaziranga National Park is an important source population for the southern parts of the North East landscape, which extend till Nagaland and Myanmar via the Karbi Anglong Hills.

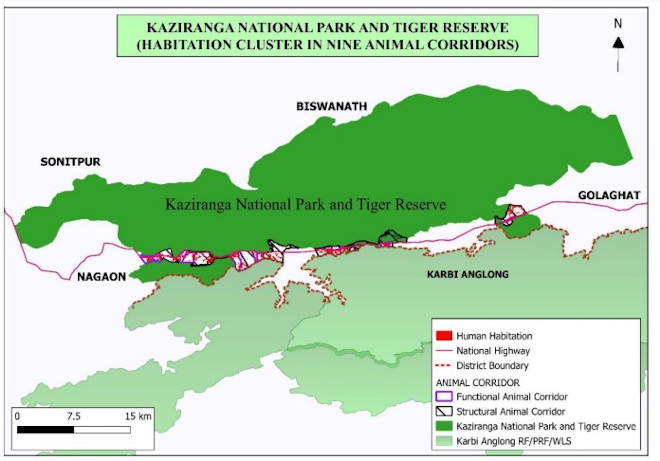

The NTCA has identified 32 landscape level tiger corridors in India, out of which 4 corridors are directly linked with Kaziranga National Park. Out of the 4 corridors linking Kaziranga, the Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong corridor is one of the most important and critical links not only for maintaining the ecosystem of Kaziranga but for providing refuge to the huge population of wildlife fauna during yearly floods. There are 9 smaller animal corridors, which are part of the larger Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong corridor (see map below).

Map showing habitat cluster in 9 animal corridors. (Source- Report on Delineation of Nine Animal Corridors Connecting Kaziranga National Park To Karbi-Anglong, May 2019)

The Karbi Anglong hills area on the southern boundary of Kaziranga acts as a watershed for the rivers flowing through the park, and is also important for providing water for agriculture and other needs of local residents. During monsoon, when the entire Kaziranga park gets inundated, the animals from the Park disperse to Karbi Anglong hills, which are on a higher elevation. This is an yearly phenomenon and this is how the entire Kaziranga ecosystem along with its wildlife has evolved over millions of years.

Originally, the Kaziranga National Park and Karbi Anglong hills were contiguous and used to function as a single ecological unit until the NH-37 (national highway) came up on the southern boundary of the Park along with human habitations, tea estates and other commercial infrastructures. These have fragmented the landscape.The NH-37 and the huge traffic volume on the highway already causes great disturbance to the movement of animals.

What is worse is that during floods, the NH-37 turns into a battle ground where Park authorities are not only tasked to keep checks on vehicle entry, but also ensure safety of animals. The mushrooming number of tourist resorts, dhabas and truck terminals have further aggravated the obstruction. Last year, 200 animals including a dozen rhinoceros died during the floods in Kaziranga as a result. However, the problem is not limited to the NH-37 alone.

A Royal Bengal Tiger took refuge inside a junk dealer’s shop during floods of 2019 (Photo- Mohammad Rafiqur Islam, owner of the shop)

Saving the Karbi Anglong for Kaziranga’s wildlife diversity

In a response to a complaint filed by a Kaziranga based activist Rohit Choudhury, on 20th April, 2018 the NTCA sent a letter to Chief Secretary, Assam, highlighting serious issues observed during a field visit undertaken by its officers in January, 2018.

The letter accompanied with a report highlighted that ‘more than 40 stone quarries have been allowed in the Karbi Anglong East and Golaghat Forest Divisions particularly in the hill slopes facing NH-37’. The report also stated that the high decibel sound and dust pollution makes it impossible for wild animals to move towards these areas. An excerpt from the conclusion from the report is presented below:

Based on the observations made in various official documents and details gathered during field visit, it is concluded that the stone mining/ quarrying and stone crushers established in the intervening area between Kaziranga and Karbi Anglong hills are responsible for destruction of wildlife corridors and vital wildlife habitat which is essential for long ranging species like Indian elephants and tigers. In addition, these stone mining/quarrying and stone crushers are also responsible for drying and siltation of several natural streams and rivulets that flow from Karbi Anglong hills towards Kaziranga. Considering the destructive impacts of quarrying/mining activity, all the stone mining/ quarrying and crusher units need to be closed down immediately. If these destructive activities are not stopped immediately then there is a high risk that Kaziranga National Park may lose its corridor and habitat connectivity with the larger Karbi Anglong landscape permanently.

The Supreme Court led Central Empowered Committee (CEC) also took cognisance of the complaint filed by Rohit Choudhury and conducted site visits in March-April 2018 and in May-June 2018. Based on site visits and meetings with concerned authorities of Kaziranga National Park (KNP) and Karbi Anglong Forest Division, the CEC submitted a report to the Supreme Court. It is important to highlight some findings below.

The barrier effect of the National Highway all along the southern boundary of KNP and disturbances caused by illegal mining/quarrying in the Karbi anglong Hills seriously impact the wildlife habitat. It is therefore imperative that the landscape connectivity with Karbi Anglong Hills and beyond in the South, and the River Brahmaputra and its islands in the North as also also connectivity with the adjoining forest areas in other territorial divisions are maintained in the interest of long term survival of the mega herbivore assemblages in the park.

However, what emerged of grave concern was that the CEC report also pointed out that the DFO (Divisional Forest Officer) of Karbi Anglong Hills Division issued permits for stone quarrying within the eco-sensitive zone of Kaziranga National Park in the Karbi Anglong Hills landscape without obtaining approval of the Standing Committee of the National Board of Wildlife. The CEC, in its report, also stated that the Karbi Anglong Autonomous Council, constituted under 6th Schedule of the Constitution of India, under which the DFO’s office falls, does not have the executive jurisdiction to decide over mining activities in its region.

Flow of this river is destroyed due to the mining activities in Karbi Anglong hills. Clicked on December 2019 (Photo: Debadityo Sinha/ Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy)

The observations by the NTCA and the CEC sufficiently exhibit the magnitude of corruption as well as the ongoing destruction of one of the most pristine and unique wildlife habitats and corridors of North East India.

Based on these findings, the Supreme Court of India on 12th April, 2019 directed a complete ban on all kinds of mining activity in the Karbi Anglong hills and the entire catchment of rivers and streams flowing into Kaziranga. A ban was also imposed on any new construction in the identified nine corridors within the Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong corridor.

Upcoming study on the current situation of the Kaziranga landscape by Vidhi

Some areas have started showing signs of natural restoration,such as this hill near Slimkhowa village in Karbi Anglong. (Photo: Debadityo Sinha/ Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy)

The implementation of the court’s directions on Kaziranga is one of the five landmark environmental cases that the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy has closely studied, the findings of which will be presented as a documentary film. The study included physical verification at the Kaziranga National Park and the mining affected areas of the Karbi Anglong district, as well as interviews with different stakeholders, including the Kaziranga National Park authorities and National Tiger Conservation Authority. The film is expected to be completed by June, 2020. The trailer of the film is available here. An introductory blog on the Kaziranga case study, written by Shyama Kuriakose can be found here.

Views are personal.