Inaccessibility Plagues Digital Education

Inaccessible education follows Students With Disabilities from the classrooms to their homes

A study conducted by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy in December 2020 in four Southern Indian states, found that the various modes of delivering digital education being used since the start of the pandemic were largely inaccessible for students with physical disabilities. For example, the government’s TV channels hosting educational content were inaccessible for students with hearing disabilities, as classes broadcast did not have subtitles or sign language interpreters. In another recent study, we systematically assessed a sample of e-textbooks and other educational materials on the Digital Infrastructure for School Education(DIKSHA) platform for accessibility using a screen-reader. We found that 68.2% of sampled links to learning resources on the website were unusable with a screen-reader software. Further, 64% of National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) textbooks and 95% of State Council for Educational Research and Training(SCERT) textbooks for states of Tamil Nadu and Telangana that were sampled were inaccessible to students with visual disabilities.

This inaccessibility can have immediate and long-term impacts on enrolment and retention of SWDs in schooling. As per a 2019 UNESCO report, 28% of children with disabilities in India are out-of-school, and dropout rates increase with each successive level of schooling. A study conducted by Swabhiman found 43% of SWDs planned to drop out due to inaccessibility of online education during COVID-19.

An Important Step in the Right Direction

Given that there is no clarity on reopening physical schools anytime soon, the Ministry of Education’s Guidelines for e-content for Children with Disabilities, is timely. It recognizes that while, “… the digital version of NCERT textbooks can be accessed from EPathshala and other portals… these digital books do not have all the features that are required for these books to be classified as accessible books.”

The document broadly calls for 1) ensuring technical accessibility as per national and international accessibility standards, and 2) undertaking pedagogical adaptation towards the goal of inclusivity.

The former is arguably easier to fix. Pedagogical adaptation on the other hand- with much of its success relying on multiple stakeholders with a necessary and in-depth understanding of how to create inclusive classrooms – is harder.

The Need for Pedagogical Adaptation is Pressing

It is clear that pedagogical adaptation is key to ensuring inclusive classrooms. Inaccessibility of education for SWDs goes far beyond just technical inaccessibility of educational materials.

In the same study on the accessibility of the DIKSHA platform, we also assessed accessibility of ‘learning activities’ within sampled chapters of NCERT e-textbooks (such as questions, activities, word problems, etc.). Of more than 900 learning activities identified in sampled NCERT e-textbooks, 52.6% were inaccessible, varying across grades and subjects. Mathematics had the most inaccessible learning activities (80%) across subjects, and Grade 1 textbooks had the most inaccessible learning activities (94.2%) across Grades.

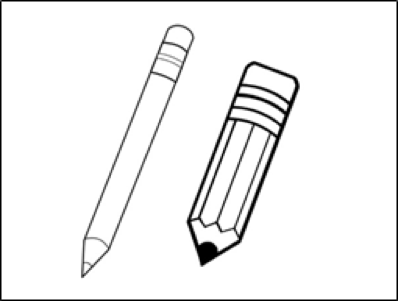

Take the example of this pre-numeracy activity from a 1st grade Mathematics textbook, where students are asked to circle the pencil that is thicker of the two pencils shown in the image. For a student with visual disability, this activity is inaccessible.

Students with visual disabilities are often asked to skip such inaccessible activities, and then topics in the curriculum. Pre-numeracy concepts like the one in the example above, form the foundation for later learning in mathematics. So, while comparing the thickness of two pencils seems like a small activity to skip, if 94% of foundational concepts learnt in Grade 1 textbooks are inaccessible, the problem is much graver.

Lack of learning despite attending a school, and especially in the early years can accumulate to an inability to keep up in later grades and ultimately lead to dropouts. Both, inaccessible curriculum and lack of knowledge among teachers on how to teach students with disabilities in their classrooms, results in such lack of learning. Reflective of this trend, students with visual disabilities are underrepresented in STEM courses in higher education, as these subjects are usually heavily reliant on visual abilities of students.

A Way Forward in UDL, Still Wrought with Hurdles

To address this, Section 3.4.4 of the guidelines describes “Pedagogical Adaptation as … adjusting assessments, materials, curriculum, or classroom environment to a student’s needs so that he/she can participate in and achieve the teaching learning goals.”

The concept of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is espoused as the underlying principle to guide this mammoth task through its 3 principles of providing multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement for diverse learners.

Re-examining the pre-numeracy example above, in its current form it relies on visual abilities of a student almost exclusively. If we allow an alternative, where the child can instead hold two pencils and compare their thickness through touch, and orally announce which pencil is thicker, we introduce multiple means of representation, action, expression and engagement for the child by providing tactile learning and understanding opportunities in addition to visual ones. The practice of UDL, in its simplest form, does this. It considers what concept the child needs to learn, and presents opportunities for learning and assessment through a multi-sensorial approach.

Systematizing pedagogical adaptation guided by UDL is not as simplistic. It would necessitate developing a cadre of professionals having an appropriate and in-depth understanding of UDL and a common goal of making education truly inclusive. As of now, we are nowhere close to this reality. Even special educators trained specifically to teach SWDs reported feeling out of depth if students with different disabilities were present in their classrooms. This is reflective of a system designed on the tenets of segregated, rather than inclusive schooling.

While we laud the importance of this document for highlighting the need for accessibility for SWDs, true inclusion requires a deeper movement toward development of an inclusive curriculum that works for all students, and a system that does not treat SWDs as an afterthought.

All views are personal.