Access to Do Digital Business in BRICS Countries

Digital Economy Blog Series: Part 3

This post is the third in our series of blogs on access to the digital economy in BRICS countries. The series tries to study “access” in broad terms, including unevenness in the quality of access. The first two posts studied various dimensions of access to the internet and access to decent work respectively. This post examines the different levels of access to conduct and thrive in digital business in BRICS countries. We have taken a wide view of digital business, including both businesses that primarily run digitally (such as sellers on online platforms), and businesses that provide digital goods and services (such as fintech companies or enterprise software offerings).

Introduction

The digital economy is characterised by an unusually high level of market concentration, where trends seem to indicate monopolies or oligopolies at the sectoral level. A significant part of this market concentration is driven by network effects in multi-sided markets, as well as data enclosures that limit competition. Network effects can occur when a platform connects multiple sides of a market, such as buyers, sellers, advertisers, researchers, and so on. The value of a platform for each side of the market increases when the other sides increase their numbers; and the more entities join, the more valuable the market gets. This creates an advantage for the market leader(s), and decreases the scope for competition by increasing the costs of switching platforms for users.

The general lack of competition in the digital economy means that there may not be enough incentive for innovation under private capital. It also means that there is an extraordinary level of concentrated control over the directions technological development can take. While the digital economy has provided greater access to opportunities for businesses through the use of the internet, the nature of digital economy entities also has resulted in the stratification of digital business. Entrants into the market when the digital economy was at a nascent stage have now established practices and dominate the digital business space, and are at a position to dictate terms to smaller, newer business entities.

Any index that measures the “ease of doing business” (EodB) in the digital economy will thus be strengthened by accounting for the presence and degree of competitive markets. Our analysis is designed to be complementary to indices that measure EodB, such as this one published in the Harvard Business Review. We also differ from many of these indices in certain aspects, finding that they over-attribute importance to removing labour rights or undoing data flow restrictions, and also that they focus primarily on the ease of international businesses to carry out operations in a given country.

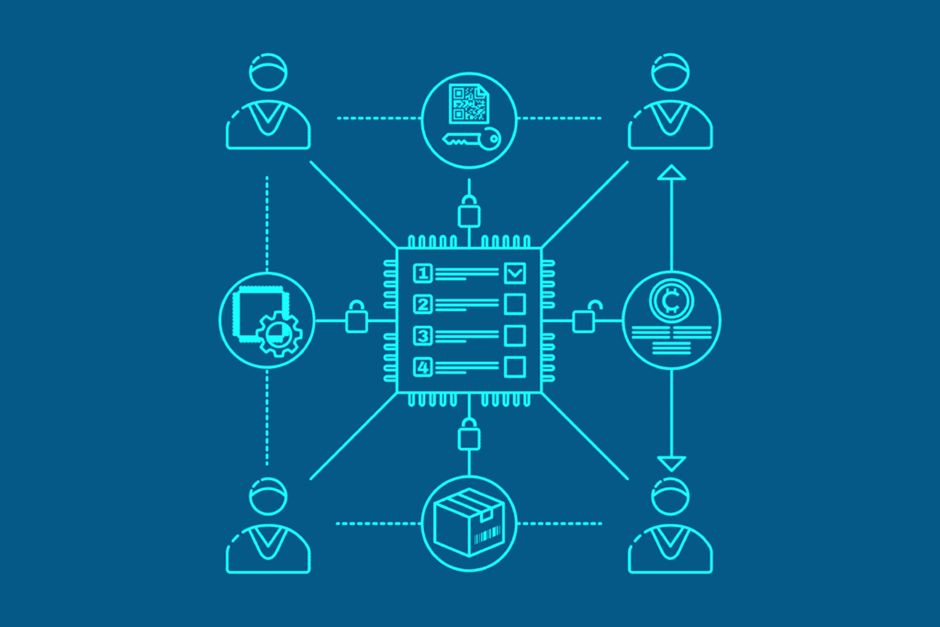

We have chosen to shift focus on the access to do digital business in the presence of market leaders that may unfairly increase barriers to entry in digital markets. Measuring access in this context therefore means measuring the regulation of existing markets (broadly categorised below as platform regulations) and the creation or reshaping of new markets (broadly categorised below as digital public infrastructure).

Platform regulation

E-commerce entities tend to platformise, i.e., adopt several tendencies of a platform over the course of their operations. They often operate both as regulators and participants in the digital marketplace that they create. In other words, they often aggregate products or services supplied by vendors on their platforms, and parallelly sell their own products or services on the same platform.

Further, e-commerce entities that bundle logistical services such as delivery and returns offer greater access to, and reduce costs for, businesses online. However, this logistical benefit can be abused by e-commerce entities by differential treatment in algorithmic rankings for those sellers who do not opt into the platform’s logistics. This has sometimes led to regulatory action. In 2021, Italy’s competition regulator imposed a $1.3 billion fine on Amazon for using its dominance in the logistics space by treating poorly businesses that did not sign up for the ‘Fulfilled by Amazon’ program that bundles logistics services with platform access.

Thus the current model of platform based e-commerce has given rise to concerns of excessive power wielded by platforms. The unregulated space between platforms and sellers allows platforms to control seller behaviour through contractual obligations, and to control seller performance through sequencing, ranking and product display design on its interface. It also allows platforms to access and profit from data generated in the interactions between the consumer and the seller. While well-established consumer protection frameworks govern buyer-seller interaction, the platform-business space is largely unregulated in several countries.

When platforms are regulated, it is usually in an ex post manner, i.e., by levying penalties and orders after an incident occurs and is investigated. In certain jurisdictions discussed below, this is being complemented with ex ante regulation of platforms, i.e., setting out a regulatory framework that deals with potential concerns and future behaviour of platforms. We also notice a global trend of regulating platforms through the lens of competition law. This can be attributed in part to the fact that competition laws are enacted to protect retail entities from abuse of dominant position by a market leader, cartelisation, or anti-competitive gatekeeping that undermines the ability of sellers to freely exert their presence in the market.

Following is a list of the kind of regulations that are required to improve access to do digital business.

Platform neutrality and transparency

The power to opaquely and unduly influence a buyer or bury a seller through algorithmic sequencing (such as displaying search results in a manipulated order) detracts from the role of the platform of bringing sellers and buyers together. In this vein, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) has highlighted concerns regarding platform neutrality in a study on e-commerce entities in India. Proposed solutions to the lack of neutrality include requiring transparency in how platforms rank sellers and undertake algorithmic sequencing of listings, thereby allowing market forces to work as intended in the absence of opaque tampering.

Limits on access to aggregated third-party seller data

The interaction between consumers and sellers generates massive amounts of data that reflects consumer preferences and other valuable insights. This data is collected and used by platforms, which allows them disproportionate levels of market influence. For example, access to non-public business data allows e-commerce platforms to record the number of views and clicks received by a product, replicate popular metrics at cheaper costs, and promote such products through ranking and banner ads.

E-commerce platforms gain subsidised market information in this way. This information would otherwise involve copious amounts of expenditure in market research and product testing. Access to third-party seller data thus provides platforms a competitive advantage in the e-commerce marketplace. Meaningful access to doing digital business includes regulating the use of this information. This may be achieved through restrictions on platform access to third-party seller data, requiring sellers to be provided with complete access to the data generated by consumers regarding their products, and creating mechanisms for sellers to use this data collectively, including by porting it to a competitor.

Economic leverage over listed sellers

The access to consumers provided to sellers by platforms allows for a serious asymmetry from an economic perspective. Platforms routinely engage in leveraging this asymmetry through exclusivity agreements, requiring businesses to offer the lowest prices on their platform (known as price parity clauses) and offering deep discounts in addition to discounts offered by the sellers. Further, e-commerce platforms may reserve the right to unilaterally change the terms of contracts with listed sellers. This position does not contemplate negotiations with sellers, and presents sellers with a binary choice of having to accept the new terms or to terminate the agreement at their end, incurring costs and losing access to a wider market. Examples can be seen in clause 15 of Amazon’s developer services agreement or clause 9 of Apple’s developer agreement.

In response, the European Parliament has adopted the Digital Markets Act (DMA), targeting significant platform entities working in core platform-based services. Article 6 of the DMA restricts platforms from using seller-generated data, aggregating data collected through its network applications, or from requiring businesses to adopt bundled services offered by platform entities. It further requires platforms to provide business users with access rankings, clicks and views data on search engines, so that businesses offering the services are able to optimise their services and effectively contest in the market.

Similar proposals to recognise and regulate certain platform entities have been mooted internationally in recent years in the UK, Germany and Japan. This form of ex ante regulation may allow for reducing barriers to access for businesses in the digital economy.

Platform regulation in BRICS countries

The following paragraphs examine the regulation of platforms in BRICS countries insofar as it is intended to improve the access to do digital business.

Brazil

Currently, Brazil does not regulate platform behaviour through ex ante laws. However, the Brazilian competition regulator Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica (CADE) has reviewed platform behaviour from an antitrust lens in recent years. In 2021, the Administrative Tribunal of the CADE advised a prominent fuel distribution company on the proposed use of algorithms to negotiate fuel prices with retail sellers. The tribunal advised that the algorithmic price recommendations must be set below the retailers’ resale price, must be tailored to each specific retailer based on their unique considerations, and that the algorithm and database must be exclusively used by the distribution company. In another instance, the use of ‘wide’ price parity clauses by e-travel agencies such as Booking.com, Expedia and Decolar.com in contracts with hotels was deemed anti-competitive by the CADE. In this instance, wide price parity clauses referred to clauses where the hotel was not permitted to offer better prices than that offered to the e-travel agencies in question, to any third party reservation sites. Additionally, the CADE held that narrow parity clauses requiring hotels to offer terms similar to their own website was permissible, to prevent the free rider effect, i.e., to prevent sellers and consumers from connecting on the platform but finalising their transaction separately.

Russia

Currently, Russia does not regulate platform behaviour through ex ante laws. However, the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS), Russia’s competition regulator, has recently provided ex post relief on two major cases involving anti-competitive behaviour by platform entities. In 2017, Kaspersky Lab approached the FAS regarding Microsoft’s insufficient timelines given to developers for creating anti-virus packages and switching users automatically to Windows Defender upon upgrading operating system software. FAS issued a warning to Microsoft about its anti-competitive behaviour. The FAS has similarly ruled against Apple for unfair terms imposed on developers in its app store, against Booking.com for wide price parity clauses and against Yandex for manipulating search results to lead users to Yandex-affiliated services. The Fifth Antimonopoly Package has been introduced by the FAS reportedly proposes to amend Russia’s competition law to regulate abuse by digital giants and to recognise network effects.

India

India’s Foreign Direct Policy, 2020 (FDI Policy) states that e-commerce entities that operate as ‘marketplaces’ must not exercise ownership or control over the inventory being sold. In effect, the FDI Policy discourages platforms with foreign investment to sell their own inventory on their own platforms. Nevertheless, in a recent case involving Amazon India in the Karnataka High Court, the Court accepted the CCI’s submission that popular e-commerce platforms have found ways to circumvent these restrictions by partnering or affiliating with preferred sellers who are ranked higher. Additionally, the obligation to separate marketplace and inventory models of e-commerce is not applicable to domestic e-commerce entities, exposing a lacunae in the regulatory set-up.

Currently, India does not in general regulate platform behaviour through ex ante laws. However, the CCI has provided ex post relief to businesses against price parity clauses by platforms. The CCI’s e-commerce market study in India notes notes that the presence of a few major e-commerce platforms and a fragmented, disunited group of sellers creates a situation with asymmetrical bargaining power. Similarly, the food delivery e-marketplace in India has seen evidence of exclusivity clauses. Another example is when MakeMyTrip India entered into an exclusivity agreement with Treebo, wherein Treebo was prohibited from listing certain rooms on competitor e-travel agency platforms three days prior to check-in dates. This was prima facie viewed by the CCI as anti-competitive. CCI has also commenced investigations where platform price parity clauses have been set by e-travel agencies on hotel chains to discourage them from offering better prices than those listed on its website.

China

The E-Commerce Law, 2018 states that e-commerce platforms cannot take advantage of third-party sellers operating on their platform through the use of service agreements, transaction rules, technologies or any unreasonable fees, conditions or restrictions (Article 35). Additionally, any e-commerce platform that is also providing its own products or services on its platform along with third-party business listings must notify the same to consumers (Article 37). In February 2021, China’s State Administration of Market Regulation (SAMR) issued the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines for the Platform Economy Industries, 2021 (AM Platform Guidelines), under the Anti-Monopoly Law of the People’s Republic of China, 2008. Chapter II of the AM Platform Guidelines prohibits platform entities from entering into or implementing vertical or horizontal monopoly agreements, including through the use of algorithms, price setting via platform rules, or the use of platforms to collect commercially sensitive data. Chapter III further prohibits abuse of dominant positions through deep discounting, exclusivity agreements, mandated bundling of services or differential treatments. In 2021, the SAMR imposed a $2.75 billion fine on e-commerce giant Alibaba for tying sellers exclusively to its platform since 2015. A fine of $527.4 million was imposed on food delivery platform Meituan for similarly tying sellers exclusively to its platform. SAMR has further imposed a fine of $464,000 on online discount retailer platform Vipshop. In this case, Vipshop had developed a system to collect data on brands to give itself a competitive advantage, and had further used its system to influence transactions and block sales of particular brands.

South Africa

Section 5 of the Competition Amendment Act, 2018 contemplates the influence of dominant entities not just in terms of anti-competitive behaviour directly affecting end-consumers, but also that which affects intermediate customers of services offered by that dominant entity. This would include predatory pricing by the larger entity, forcing customers to buy bundled products or services along with their desired purchases, or squeezing margins for retail vendors. These obligations, particularly regarding unfair pricing and unfair trading conditions, are applicable for notified sectors which includes the e-commerce and online services sector. These protections are vital in context of the dominance enjoyed by larger platform entities and the foregoing examples of bundled services (Amazon) and anti-competitive price parity clauses (MakeMyTrip India and Booking.com Russia). The Competition Commission, South Africa’s competition regulator, has ordered a penalty on Meta for enforcing exclusionary terms of access for its WhatsApp business API to GovChat, a South African government reporting platform. The Competition Commission further has published a study on its digital economy and has commenced a market inquiry on intermediary platforms which analyse the market asymmetry between platform entities and small and medium businesses evidenced by price parity clauses, exclusivity contracts, predation, unauthorised use of seller data etc. The market inquiry is expected to result in recommendations on platform governance.

We can therefore see that ex-post regulation is standing in for ex-ante regulation of platforms in BRICS countries except China, and that all these countries seem to be preparing the ground for ex-ante regulations. The next section explores the role of digital public infrastructure in improving access to do digital business in BRICS countries.

Digital public infrastructure

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) is a term commonly used to refer to digital products and services that “enable basic functions essential for public and private service delivery, i.e. collaboration, commerce, and governance.”

The first significant use of DPI in current times is improving provision of non-digital services through digital means. This includes financial inclusion through digital identity verification, agricultural trading using public digital platforms, etc. These interventions seek to broaden access to physical goods and services with the use of public investment in digital infrastructure.

The second significant use of DPI in current times is ensuring that infrastructural or infrastructure-like parts of the digital ecosystem remain under public control, oriented towards the public good. This includes public platforms that enable digital payments among different banks, financial companies and the public. It also includes public open data platforms that make digital data available for a wide variety of commercial and/or non-commercial uses. The rationale for the second use includes creating a level playing field for all market players in the digital economy, under the well-supported assumption that public provision of the “marketplace” is more likely to create such a level playing field.

Across the world, DPI is being seen as one of many solutions to societal and economic problems in the digital age. The UN Secretary General has spoken about the role of DPI in battling the pandemic and potentially helping solve the issues of climate change and inequality. Various philanthropic and investment organisations have called for global funding for DPI.

In the UK, an example of DPI is Gov.uk Notify, a platform that allows various government departments to notify the public. Another example is Sri Lanka’s Covid-19 tracking system, which was built on top of an open-source health information management platform. Digital identity systems too can be a part of DPI. The following paragraphs elaborate on DPI and plans for DPI in BRICS countries. We have focused on the manner in which DPI can improve the access to do digital business.

Brazil

While there is no overarching government framework for DPI in Brazil, there are instances of DPI being implemented and conceptualised. In particular, the health sector has seen the development of DPI in the backdrop of Covid-19. This DPI architecture is built around the “Conecte SUS” program. SUS or Unified Health System is the acronym for Brazil’s public health system. Conecte SUS is a health architecture that aims to provide interoperability and consent management for health information. Already, data solutions are being built on top of the platform, including for healthcare forecasting through the Integrated Platform for Evaluation and Forecasting (IPEF), created by a university using datasets from the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Social Development and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

One challenge that has been experienced in the digital health system of Brazil is that primary health data requires uniform standards for computerisation. The pandemic fuelled an increase in computerisation, but gaps in uniformity remain, generating duplicate records and affecting usability of data.

Brazil also has an advanced open banking system, another instance of DPI. Open banking in Brazil was pioneered by its central bank, which issued data sharing standards and other regulations. The central bank has also developed and maintains a public instant payment platform called Pix, which even allows people without bank accounts to instantly transfer money (through a digital wallet, for example). Pix transactions were equivalent to reportedly 80 percent of card transactions in volume, and 17 percent of Pix transactions have been from individuals to businesses. The entire gamut of open banking services in Brazil includes the sharing of data on financial transactions, insurance and investment.

Russia

The Russia-Ukraine war and the response of Russia’s adversaries has created the conditions for the testing of much of Russia’s DPI. Visa, MasterCard and American Express suspended some of their services in Russia following US sanctions on Russia. However, Russia had already created a domestic payments alternative called the National Card Payment System and a card called Mir in response to prior sanctions. Russia has also required data localisation for payments, ensuring minimal disruption in local payments for the general population despite sanctions. Partly due to government mandates on use, Mir cards control 30 percent of the market share in Russia now.

Russia has also created a publicly owned platform called TechNet as part of its National Technology Initiative. TechNet is a platform that provides solutions for the digitalisation of the industrial sector. It is expected to assist in the digitalisation of automotives, ship construction, and nuclear power. One of the stated goals of TechNet is to create 40 “Factories of the Future” by 2035, i.e., factories that have integrated digital technological processes for production.

As noted by the World Bank, Russia has in general been able to build strong domestic digital infrastructure and platforms that can support the development and use of new technologies. The World Bank has also recommended the “launch of open government-driven digital platforms to enable a variety of interactions between public and private sector players” as a way to enable the digital transformation of Russia’s economy. This description essentially refers to DPI.

India

In recent years, India has been making an explicit push for DPI. Its 2022 Union Budget lists DPI as a priority area, and the country is keen to build on the (relative, qualified) success of its DPI projects such as the United Payments Interface (UPI) or other parts of India Stack. For example, the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) is an effort at infrastructuralising the platform layer of e-commerce, or in other words, providing a public platform for e-commerce operations to level the playing field between different platforms as well as between platforms and third-party sellers.

Future development of DPI in India is expected to be sectoral, such as DPI for health, skilling, logistics and mobility. Policy analysts have cautioned, however, that data protection, community engagement and effective governance are critical to the success of these initiatives. Government plans including the India Digital Ecosystem Architecture (IndEA) 2.0 also indicate a move towards more decentralisation in DPI, or a shift “from systems to ecosystems and from platforms to protocols.” A similar approach was taken in the National Open Digital Ecosystem (NODE) whitepaper released by the government, which provides a framework for creating public platforms on top of which solutions can be built by different stakeholders.

It remains to be seen how effectively India’s DPI ambitions are achieved. The “UPI model” may not be replicable in all contexts, particularly where there are strong vested interests such as in e-commerce. India’s ability to build and maintain DPI will depend on its ability to push back against both domestic and foreign monopolies that will be displaced with the introduction of DPI. The real possibility of DPI merely serving as surveillance architecture also needs to be tackled by the government through the adoption of a data protection law and other trust-building legal measures.

China

As part of the country’s Digital China policy, the government of China has focused on New-type Infrastructure (NTI) to give impetus to the creation of a digital ecosystem with cutting-edge technologies. Scholars have described NTI as “combining the characteristics of public products and emerging industries.” It has also been described as infrastructure “providing the foundation for services such as digital transformation, intelligent upgrades, and integrated innovation facilities systems.”

Importantly, the kinds of infrastructure being promoted under NTI seem to be one layer below the platform layer; for instance, 5G, advanced data centres, artificial intelligence innovations, etc. NTI also involves the digitalisation of traditional infrastructure, for instance, smart parking. In this sense, China’s approach to the DPI solution is geared more towards overall economic development rather than making publicly owned versions of existing platform models to encourage businesses. The growth of businesses is expected to be an ancillary benefit. China shares its goal of building a minimum level of digital independence with other BRICS countries, which is seen as being particularly significant in a world ridden by sanctions and political intervention in business decisions.

The global counterpart of China’s digitalisation strategy is the Digital Silk Road, a plan to improve digital infrastructure and connectivity along the Belt and Road Initiative stretch. Digital Silk Road includes both hard infrastructure (telecom networks and satellite navigation systems) and soft infrastructure (platforms and apps) provided by both public and private entities.

South Africa

South Africa’s national digital ID system has seen a high level of uptake. Digital ID systems can serve as the base for other DPI, which means that South Africa has the potential to build DPI on top of its ID architecture. Indeed, it is already emulating parts of India’s UPI model. A new National ID System (NIS) too is in the offing, one that makes it easier for public and private providers to leverage the system for identity verification. However, even the World Bank, a resolute advocate of digital ID systems, has recommended that South Africa consider a federated model of NIS rather than a centralised model.

There are sparse examples of DPI in South Africa. For instance, to make cross-border transactions easier in the Southern African region, the Southern African Development Community Real-Time Gross Settlement (SADC-RTGS) system was set up. SADC-RTGS has allowed for the smooth integration of fintech providers and banks in the region. One of the goals of SADC-RTGS is creating interoperability among market participants. Such initiatives are important because the lack of regional integration is considered to be a key reason for the stagnation of digital entrepreneurship in South Africa.

Scholars have recommended that given South Africa’s state capacity, it should focus on creating a level playing field and support local businesses to be able to pursue its own model of digital development. Another recommendation that has been made for South Africa is the drafting of a comprehensive digital industrialisation policy, one that takes into account the increasing gap between large and small firms in the digital ecosystem. Both recommendations are compatible with an approach that focuses on building DPI in South Africa.

Conclusion

Despite the forward-looking nature of platform regulations and DPI, the access to do digital business in BRICS countries hinges on a few unanswered questions. One question is that of basic infrastructure. For digital infrastructure to function smoothly, basic infrastructure needs to be built to a given minimum level, and in this sense, BRICS countries cannot leapfrog into digital infrastructure without solving for the lack of basic infrastructure. For instance, while DPI in Brazil tried to create interoperability between different types of health systems, it ran into issues due to poor internet connectivity, power fluctuation, and a shortage of personnel. The lack of digital skills is also an important impediment to the success of DPI or inclusive platforms. For businesses in particular – for instance, in the handloom sector in India, which deals in very small producers – there is evidence to show that onboarding support and skill development is critical for successful digitalisation.

The second question is one of striking a balance between reclaiming public functions through DPI or platform regulations, and avoiding technological solutionism. BRICS countries need to respond to the dismantling of public functions through private digital platforms, with its attendant market concentration. However, this response often tends to be hasty, oriented towards using technology as a crude solution for socio-economic problems, and lacks consideration of human rights. BRICS governments must take care to avoid these pitfalls.

The third question is that of funding. Stable funding has been recognised as a critical requirement for effective DPIs, leading to calls for more government investment, horizontal investment rather than isolated solutions, and more investment in replicable solutions or solutions with multiple uses. One proposed solution in the context of the European Union is that of a Public Technology Fund, proposed to be established by the European Commission, to maintain existing DPI and fund new DPI. Another proposal is for governments to fund DPI through a tax on surveillance advertising. Such a mechanism can tie together the twin levers of platform regulation (including a tax on platforms) and DPI to improve the access to do digital business.

Overall, platform regulations and DPI can function together with other, more fundamental interventions in BRICS countries to create thriving, more competitive markets with lower barriers to entry for all.