The Use of Facial Recognition Technology for Policing in Delhi

An Empirical Study of Potential Religion-Based Discrimination

The use of new technology, including facial recognition technology (FRT) by police in India brings with it questions of efficiency, surveillance, and discrimination. Existing research focuses on the legal dimensions of FRT with an emphasis on privacy. In this paper, we provide an empirical basis to understand the potential discrimination that can result from the police using FRT. We mapped police station jurisdictions and found that in Delhi, Muslims are more likely to be targeted by the police if FRT is used.

Context

FRT uses machine learning or other techniques to match or identify faces. These techniques usually require large troves of images of faces compiled into what is called a training database. The software uses this training database to “learn” how to match or identify faces.

The increasing use of FRT by the police in India is set to expand further over the next few years. However, FRT is not an error-free technology. If the training database of FRT has an over-representation of certain types of faces, the technology tends to be better at identifying such faces. Even if it does not have a training bias, the technology is rarely completely accurate and can easily misidentify faces. This means that there are chances of innocent people being wrongly identified as criminals or suspects. The use of FRT may also result in the disproportionate targeting through surveillance of certain activities like loitering, which become easier for the police to monitor.

There are a few biases inherent in policing, including that policing disproportionately targets some groups of people. Such a bias creates a skewed spatial distribution of policing, which can intensify the disproportionate targeting. This bias remains when new technology is applied to such a system. The victims of the shortcomings of policing technology will more likely be these disproportionately targeted groups.

This paper shows that two factors in particular – the uneven distribution of police stations across space, and the uneven distribution of closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras across space – are likely to result in a surveillance bias against certain sections of society more than others in Delhi.

Methodology

To understand whether some areas were more policed than others, we analysed the population distribution among police station jurisdictions. We chose this metric both due to the police’s own understanding of police stations as visible markers of authority, and the availability of the relevant data.

We mapped the ward-wise population of Delhi on top of police station jurisdiction boundaries. Areas with less population-per-jurisdiction would be over-policed as they would have more police stations per resident. Areas with more population-per-jurisdiction would be relatively under-policed as they would have fewer police stations per person. We then examined every police station jurisdiction that had fewer than 46,000 people (the lowest quintile) to see the factors that distinguished it from other areas.

Secondly – to understand the distribution of CCTV cameras across the city and see if there was any bias, we acquired the CCTV placement data for a few police districts in Delhi by filing RTIs, and mapped the data on top of police station jurisdiction data.

Results

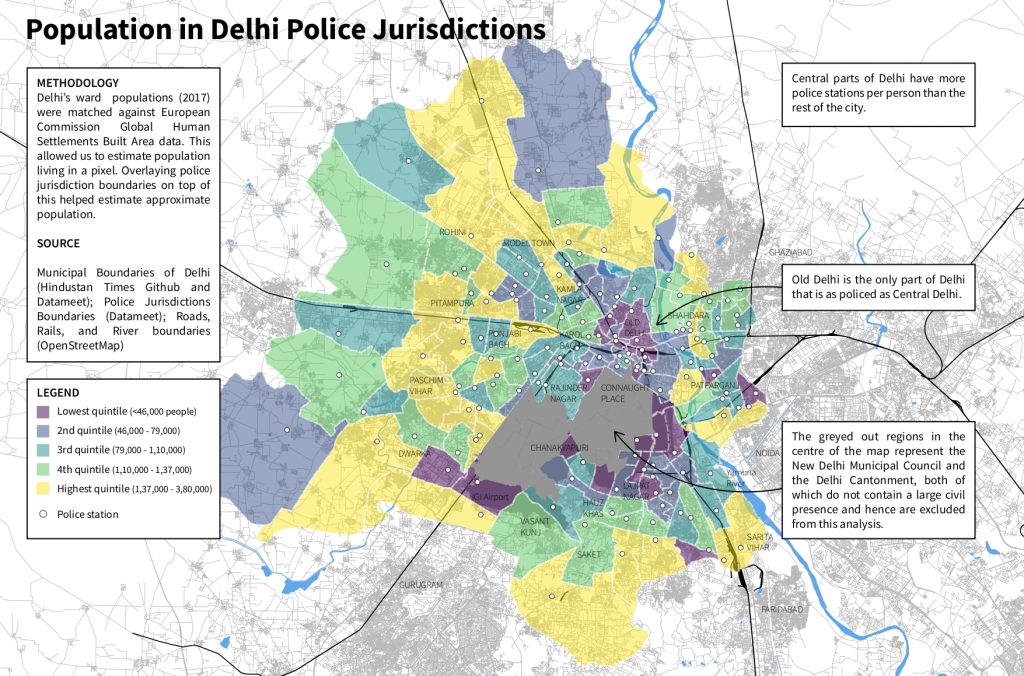

Below is the map of police station jurisdictions according to population.

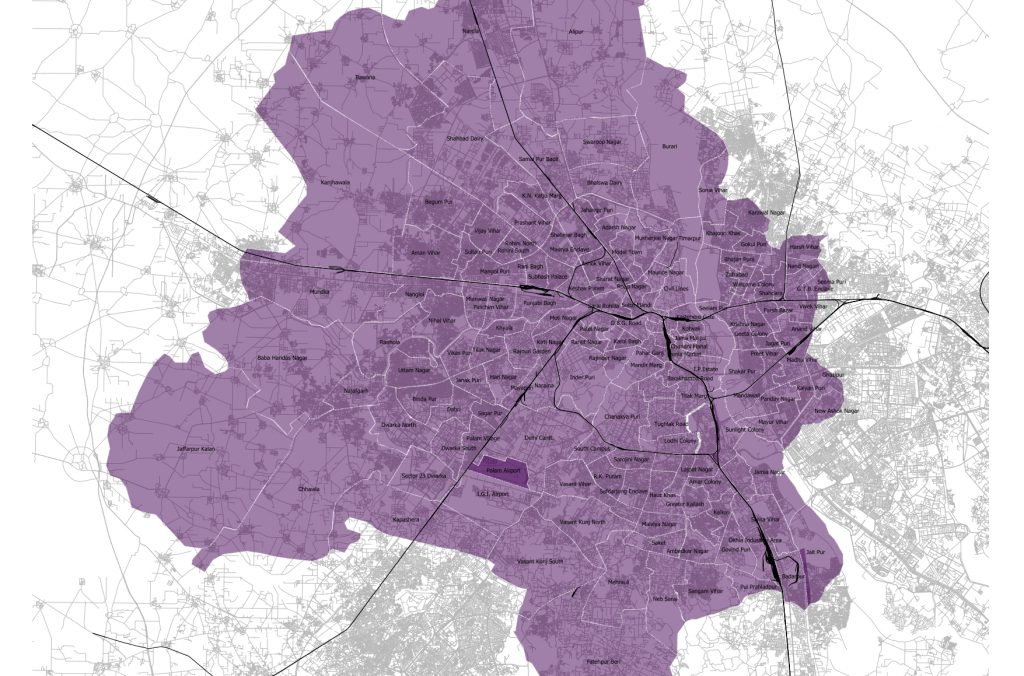

Below is the map of all labelled jurisdictions for reference.

Please note that all the greyed-out areas fall in the lowest quintile of population along with the purple areas. Visually, it is clear that:

- Police stations are spread unevenly across the city. Some police station jurisdictions are far more sparsely populated than others.

- The central areas and Old Delhi are more policed than other areas. They have relatively smaller police jurisdiction populations.

- Among the lowest quintile of police station jurisdictions (34), 14 are areas that have low civilian populations or house important government or diplomatic buildings. These include areas like Parliament Street and Connaught Place. If we disregard these areas, nearly half of the remaining over-policed areas are estimated to have a significant Muslim presence (defined as more than that of Delhi’s average share of Muslim population – 12.86%).

An important point to note here is that we are not trying to prove that the placement of police stations in Delhi is intentionally designed to over-police Muslim areas. That assertion cannot be proved with this data. However, given the fact that Muslims are represented more than the city average in the over-policed areas, and recognising historical systemic biases in policing Muslim communities in India in general and in Delhi in particular, we can reasonably state that any technological intervention that intensifies policing in Delhi will also aggravate this bias. The use of FRT in policing in Delhi will almost inevitably disproportionately affect Muslims, particularly those living in over-policed areas like Old Delhi or Nizamuddin.

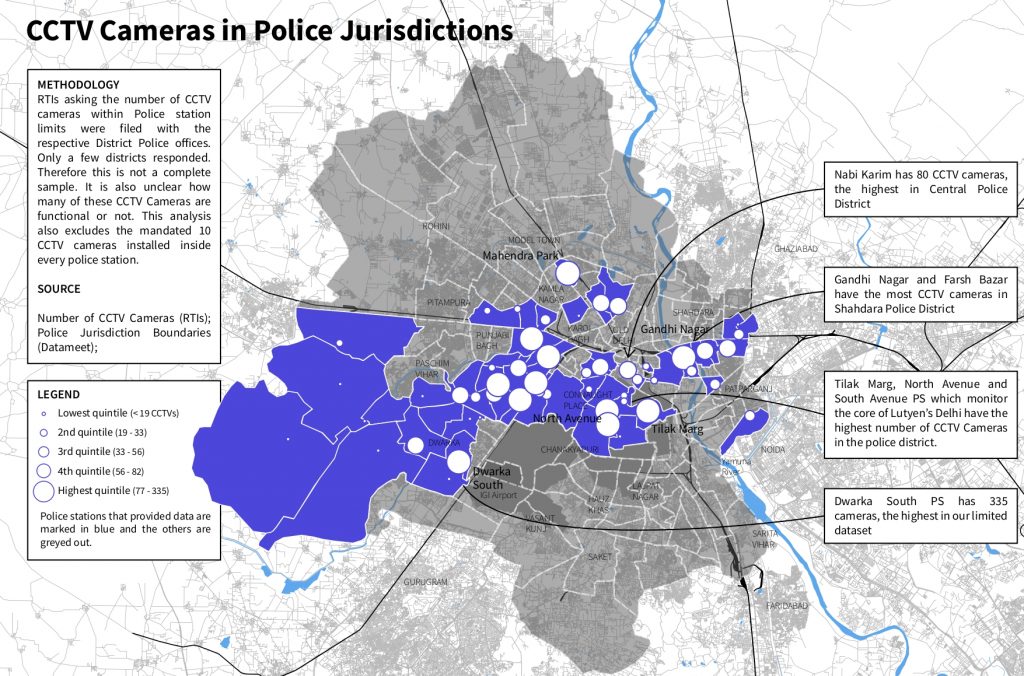

FRT in policing in Delhi is likely to employ data used from CCTV cameras across the city. This would mean that areas with relatively more CCTV cameras would be over-surveilled, over-policed and thus subject to more errors than other areas. We were able to obtain preliminary and incomplete data on the distribution of CCTV cameras across Delhi. The limited data we have obtained shows that the distribution of CCTV cameras is highly uneven across different districts.

The map of CCTV cameras by police station jurisdiction is below.

The only conclusive statement we can make based on this data is that the distribution of CCTV cameras across Delhi is not uniform. However, because of the incompleteness of the dataset, we were unable to determine whether this unevenness was due to any bias. It is difficult to discern an obvious pattern among these areas. Further, not all these CCTV cameras are functional. Due to these factors, it is not possible to comment on the nature of the unevenness of CCTV camera placement across Delhi.

Recommendations

We have shown that in Delhi, the use of FRT by the police is likely to disproportionately affect Muslims because of the over-policing of some areas with significant Muslim populations, combined with police biases. In general, the use of FRT by Delhi Police is likely to have uneven impacts on different populations due to spatial skew, CCTV placement skew, and biases.

Such disproportionate impacts would pose serious challenges to the right to equality, and we therefore recommend that the use of FRT by the police in Delhi be halted until the questions of equality and over-policing are examined by the public and public representatives.

Police biases related to caste, homelessness and sex work can also have implications on the spatial distribution of technology-enabled policing. While we have not explored these questions in this paper, the implications of FRT and other technologies on policing these groups is an important area for further analysis.

It is also not the case that an equal and unbiased deployment of FRT by the police will necessarily benefit the public. The use of FRT in policing can impact privacy and liberty of people independently of bias as well, and therefore the effects of such general deployment should also be examined.

This is the second of a series of papers. Access the first Working Paper here.