Fair and Competitive Digital Markets for India

The Report of the Committee on Digital Competition Law and the Draft Digital Competition Bill

- India’s Digital Markets and Need for Regulation

India has emerged as one of the largest and fastest-growing digital markets globally. Digitalisation has simultaneously spurred the growth of sectors such as e-commerce, and the development of innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence. Consequently, a tidal wave of new digital consumers has been brought into the fold. For instance, almost 70% of all Indian internet users have used at least one form of a social networking platform. Similarly, India’s booming e-commerce market space has about 125 million users and will see an addition of 80 million online users by 2025.

Digitalisation has been particularly driven by large digital enterprises, which have so far been regulated in a fragmented fashion in India. The business models of such enterprises have given rise to a variety of anti-competitive concerns, such as unfair business practices and unilateral discriminatory policies. The Competition Commission of India (‘CCI’) has taken cognisance of some cases of anti-competitive conduct by large digital enterprises markets, including Google, MakeMyTrip-Go and Oyo.

As part of its comprehensive review of the competition regime in India, the Competition Law Review Committee (‘CLRC’) took note of these emergent concerns in digital markets. Accordingly, the CLRC recommended certain amendments to the Competition Act, 2002 (‘Competition Act’), for instance, to include ‘data’ within the definition of ‘price’, and to include ‘network effects’ as a parameter for assessing the dominance of an enterprise. Ultimately, however, on whether a new antitrust framework would be necessitated for digital markets, the CLRC recommended a standby approach and a periodic review of global emerging trends in digital market regulation.

Cognisant of these developments and the marked differences between traditional markets and digital markets, the 53rd Parliamentary Standing Committee Report in December 2022 (‘53rd Parliamentary Report’) identified 10 anti-competitive practices (‘ACP(s)’) commonly engaged in by Big Tech companies. The 53rd Parliamentary Report acknowledged that these ACPs are enabled by dynamisms in digital markets such as robust network effects and economies of scale and scope. Large digital enterprises freely engaging in ACPs leads to a ‘winner-takes-most’ outcome, wherein the markets tip in favour of the large incumbent. Safeguarding against this ‘winner-takes-most’ outcome may not be feasible under the ex-post framework of the Competition Act, wherein enforcement proceedings are lengthy and enforcement begins after the harm has already occurred. Therefore, the 53rd Parliamentary Report recommended enacting a separate ex-ante competition law for digital markets with a view to prevent anti-competitive harm from occurring.

Against this backdrop, the Committee on Digital Competition Law (‘CDCL/ Committee’) was constituted in February 2023 to examine the need for an ex-ante competition framework to specifically regulate digital markets. The Committee was entrusted with reviewing whether the existing regulatory landscape for digital markets, including the Competition Act, was sufficient to regulate digital markets adequately. The Committee was also tasked with examining global practices on regulating digital markets. The final Report of the Committee was released on 12 March 2024.

Vidhi has closely assisted the Committee in providing drafting and research inputs for the CDCL Report throughout the duration of the Committee.

II. The CDCL Report and the Key Recommendations of the Committee

A. Intent and Working Process of Committee

The Committee studied the ex-post framework under the Competition Act and its possible limitations in addressing the peculiarities of digital markets. The Committee further examined legislative instruments that have interfaces with digital markets regulation in India such as e-commerce, data privacy, consumer protection and information technology, including the Draft E-commerce Policy 2019, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, the Consumer Protection Act 2019, and rules under the Information Technology Act, 2000 such as the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021.

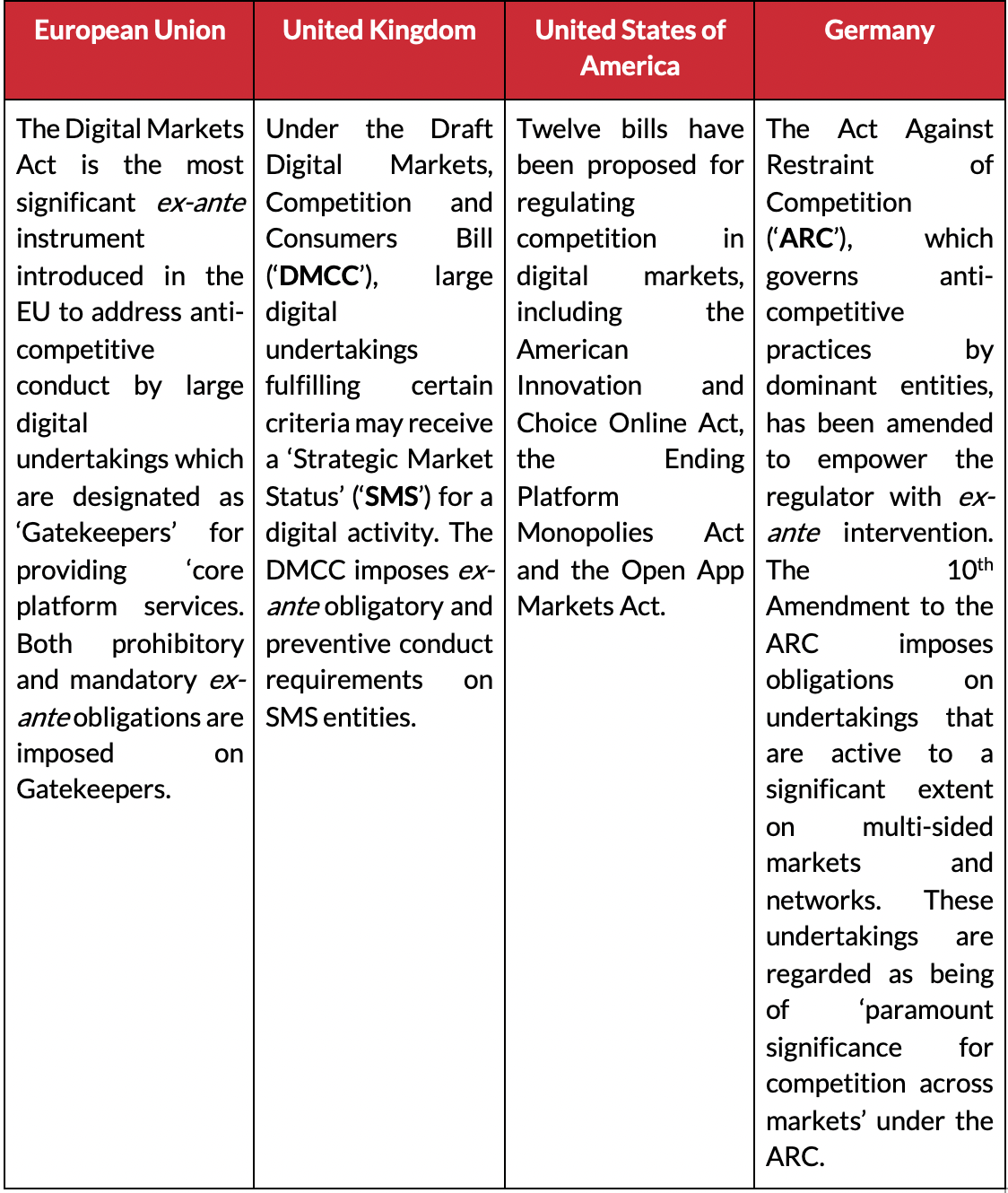

The Committee also studied ex-ante instruments pertaining to digital markets across 11 jurisdictions, notably:

The Committee also examined developments in the regulation of digital markets in jurisdictions such as China, South Korea, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, and Canada.

B. Key Findings and Recommendations of the Committee

Based on comprehensive deliberation, the Committee found that the existing domestic legislative instruments are unable to holistically address anti-competitive practices prevalent in digital markets. Further, the Competition Act, originally designed for traditional markets, entails an ex-post regulatory framework and lengthy enforcement proceedings, which may not be well-suited for fast-paced digital markets. The Committee also found that there is emerging international regulatory consensus on the need for ex-ante regulation of digital markets.The Committee has three main recommendations: (i) the need for India’s digital markets to be governed by a new ex-antecompetition law to ensure timely intervention against large digital enterprises engaging in ACPs before the anti-competitive harm occurs, and which is meant to complement the existing ex-postframework under the Competition Act; (ii) the need to strengthen technical capacity within the CCI’s Digital Markets and Data Unit (‘DMDU’) by onboarding technology experts to navigate the swiftly changing landscape of digital markets; and (iii) the need for a separate bench to be constituted within the NCLAT for speedy disposal of competition appeals, particularly those relating to digital markets.

The key features of the draft ex-ante legislation as deliberated upon extensively by the Committee, i.e. the Draft Digital Competition Bill (‘Draft DCB’), are:

1.Associate Digital Enterprises: With the intent to ensure that enterprises are not able to circumvent their obligations, the Draft DCB empowers the CCI to designate group enterprises that are directly or indirectly involved in the provision of CDS with SSDEs as Associate Digital Enterprises (‘ADE’). The Draft DCB obligates notifying enterprises to also notify their group entities directly or indirectly involved in providing CDS, such that the CCI is accorded flexibility to identify the most appropriate entities for designation.

2. Obligations: The Draft DCB provides for overarching principle-based obligations for SSDEs and ADEs. The CCI has been tasked with specifying the particulars of such obligations through regulations. Recognising that not all SSDEs and ADEs wield the same degree of market influence, the Draft DCB empowers the CCI to provide differential obligations for each CDS based on factors such as business models and size of the user base.

3. Exemptions: The CCI is empowered to exempt SSDE’s obligations under the Draft DCB on certain grounds, such as cybersecurity and the requirement of any law in force. The CCI will provide the specificities of such exemptions through regulations which are tailored to each CDS. The Draft DCB also empowers the Central Government to exempt enterprises from its applicability based on certain grounds such as public interest or interest of the security of the state.

4. Enforcement: The Draft DCB largely borrows its procedural framework from the Competition Act. The appellate authority under the Draft DCB is the NCLAT.

5. Remedies: Penalties for contravention of the obligations under the Draft DCB, harmonised with the Competition Act, are capped at a maximum of 10% of the global turnover of the SSDE. For the provision of no information or inaccurate information as required under the Draft DCB, penalties of up to 1% of the turnover of the enterprise may be levied. Notably, in cases where the SSDE is part of a group of enterprises, the ‘global turnover’ cap is calculated based on the entire group’s turnover. Penalty amounts will be determined by the CCI in accordance with the penalty guidelines under the Draft DCB.

III. Conclusion

The pivotal recommendations of the Committee as enshrined in the Draft DCB herald a new era of India’s competition law. Poised to be in line with international jurisdictions on regulating digital markets, the Draft DCB provides a principle-based framework for ex-ante obligations which will be particularised through regulations framed by the CCI. In the spirit of participatory antitrust, the Draft DCB is also possibly set for a fresh round of stakeholder consultations. The CCI’s efforts to bolster its technical capacity under the DMDU reflect a proactive attempt towards aligning India’s regulatory technical expertise with global benchmarks.

Vidhi has previously been engaged with the CLRC by participating in meetings for deliberation on legal issues, conducting legal research and providing drafting support. Subsequently, Vidhi deposed before the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on E-commerce, wherein Vidhi’s submissions as part of the deposition were included in the Parliament’s 172nd Report on Promotion and Regulation of E-commerce. Leading up from the CLRC, Vidhi assisted the MCA through research, drafting and engagement on stakeholder consultations for the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2023. Vidhi has also published independent reports contributing to the discourse on India’s competition law regime in 2017, 2021 and 2022.