End of Life Care in India

A Model Legal Framework 2.0

The Covid-19 pandemic has compelled people to confront their mortality. The prospect of being in hospitals, isolated from friends and family, further heightened anxieties about decision-making at the end of life. Issues around end-of-life care decision-making are, however, not unique to Covid-19 alone and are confronted by doctors and patients in critical care settings on a daily basis. Lack of legal certainty and fear of prosecution often prevents doctors from taking ethically sound decisions.

To address this issue, the Vidhi and the End of Life Care in India Task Force (ELICIT) have come together to create a model legal framework 2.0 on end of life care in India which furthers both patients’ rights and ethical best practices while being alive to the realities and constraints of real-life critical care settings in India.

Context

In March 2018, the Supreme Court of India, in Common Cause v Union of India, delivered a judgment that:

- Recognised the rights of adults with decision-making capacity to refuse medical treatment, including life-sustaining treatment, such as ventilation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Recognised the right of adults with decision-making capacity to execute advance medical directives or ‘living wills’.

- Permitted the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment from persons who neither possess decision-making capacity nor have executed advance medical directives.

- Laid down guidelines for the implementation of advance medical directives and the withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

The Problem

The Supreme Court judgment has been difficult to implement in practice for the following reasons:

- Judicial Magistrates of the First Class, in the presence of whom an advance medical directive must be executed, are not aware of their duties under this judgment. Very few persons have successfully executed advance medical directives since the judgment was passed.

- The judgment lays down a three-tier process before life-sustaining treatment is permitted to be withheld or withdrawn. This requires approval by an internal hospital medical board, an external board constituted by the Collector, and a visit to the hospital by the Judicial Magistrate of the First Class. In real life critical care settings, there is simply not enough time to obtain so many approvals. In any case, the external boards required to be set up by jurisdictional Collectors have not been constituted. As a result, and to the best of our knowledge, no hospital has been able to implement the Supreme Court-mandated procedure to the letter.

In the absence of a workable procedure for the withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, healthcare professionals find themselves unsure of the appropriate course of action at the end of life. They are hesitant to act in accordance with professional medical guidelines on the withholding or withdrawal of such treatment for fear of legal action. As a result, patients are subjected to potentially non-beneficial treatment that may be against their wishes.

Developments Since the Supreme Court Judgment

The following developments have taken place since the Court’s judgment in 2018:

- Hospitals like the Manipal Group of Hospitals and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, have developed their own internal guidelines on end of life care.

- An expert group of the Indian Council of Medical Research has issued Consensus Guidelines on ‘Do Not Attempt Resuscitation’ to guide healthcare professionals on the appropriate use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and the process to be observed when a decision not to attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation is taken.

- The Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine has filed an application for clarification in the Supreme Court, requesting a modification of the Supreme Court’s guidelines in Common Cause v Union of India. The Court has directed the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare to convene a meeting of all relevant stakeholders to reach a consensus. No meeting has been convened yet.

- ELICIT and the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy have drafted a model legal framework for end of life care, as a more comprehensive and workable alternative to the Supreme Court’s guidelines. Version 1.0 of this model bill can be accessed here.

- ELICIT and Vidhi held consultations with healthcare professionals, hospital administrators, patients, lawyers and civil society organisations on Version 1.0 of the bill. The feedback received at these consultations has been incorporated into Version 2.0 of the model bill.

Key Features of the Model Legal Framework for End of Life Care 2.0:

Protection of Patient Rights

- The bill expressly recognises and protects patient rights in relation to end of life care (Chapter II).

- It imposes a positive, progressive obligation on the appropriate government to guarantee access to end of life care (Clause 3) by taking steps to integrate end of life care, including palliative care, in general healthcare services at all levels of healthcare, and by implementing appropriate training for healthcare practitioners.

- Drawing on the Patient Rights Charter, it imposes an obligation on healthcare establishments to release the body of the deceased patient (Clause 8) and to grant patients, their next friend, their surrogates and their legal heirs the right to access information and patient records (Clause 10).

- Of particular significance is the recognition of the right to a ‘dignified transfer’ (Clause 7). The implication of this is that healthcare establishments can no longer ‘discharge against medical advice’, leaving terminally-ill patients to fend for themselves once they have decided not to continue life-sustaining treatment. Instead, they must ensure that patients are discharged and subsequently transferred to another healthcare establishment or their homes or other places of choosing while ensuring continuing care to the patient, including end of life care.

- All adult patients are conferred the right to exercise healthcare decision-making capacity (Clause 11). The corresponding obligation on healthcare establishments is to provide all manner of support to patients to enable them to realise this right. This support could take the form of allowing a trusted support person or next friend to assist the patient in exercising decision-making capacity.

- The bill recognises not just relatives (through blood or marriage) as capable of acting on behalf of patients who may have lost decision-making capacity but also de facto spouses or partners with whom patients have relationships in the nature of marriage or even friends of long standing (Clause 2(q)).

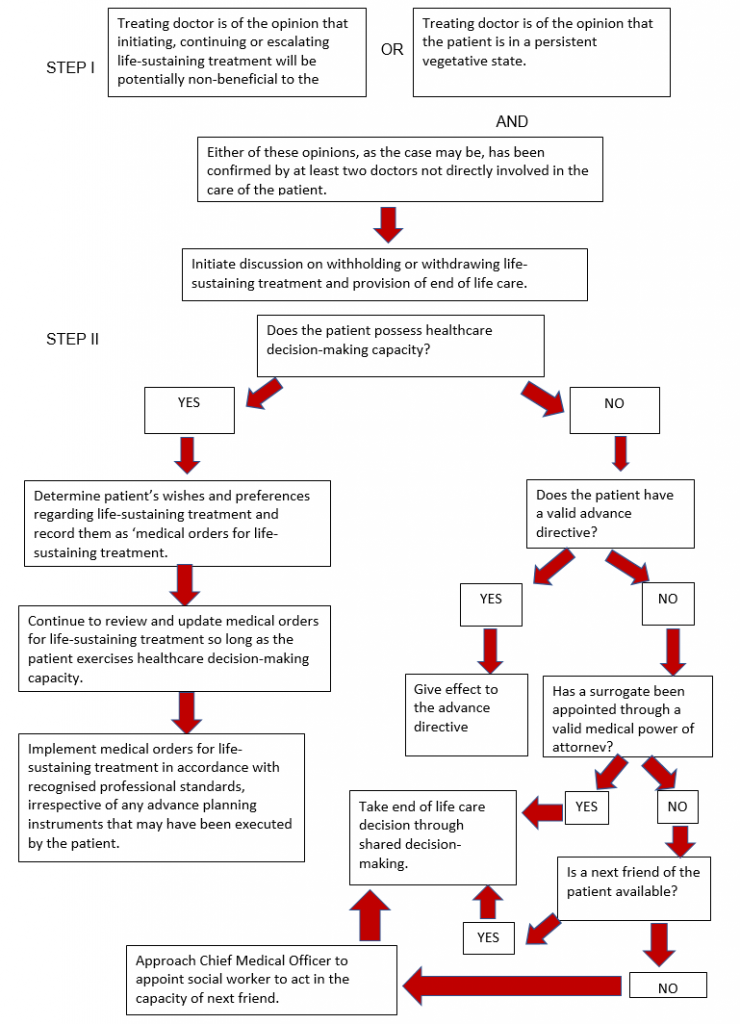

Simplified End of Life Decision-Making

- The process for end of life decision-making has been streamlined (Chapter III) and is explained in the flowchart below.

Execution and Interpretation of Advance Planning Instruments

- The process of executing advance planning instruments has been simplified, requiring the presence of only two witnesses (Clause 21).

- The bill contains a provision to recognise advance planning instruments executed in other countries (Clause 29).

- Where there are doubts regarding the validity or interpretation of advance planning instruments, healthcare establishments or surrogates or next friends of patients may approach the Mental Health Review Board set up under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (Clause 24).

Safeguards

- The bill requires healthcare establishments with more than 50 beds to set up end of life care committees that can audit end of life decisions. Other establishments may use end of life care committees that are to be set up by the Chief Medical Officer of each district (Clauses 30 and 31).

- End of life care committees are required to record the findings of their audit in an audit report, which is to form part of the patient’s record, with a copy of it also being forwarded to the District Magistrate and Chief Medical Officer of the district (Clause 19).

- The District Magistrate or Chief Medical Officer may take appropriate civil or criminal action if the end of life care committee finds that end of life decisions were carried out with demonstrated disregard for recognised professional standards (Clause 19).

Draft Living Will and Instructions

The End of Life Care Task Force in India has drafted a model Living Will/Advance Directive which can be used by people to plan for their end of life decisions in advance. The model Living Will allows the person to make a declaration regarding their wishes to decline receiving life-sustaining treatment including artificial respiration and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The Living Will also allows the person to appoint a healthcare power of attorney or surrogate decision maker to implement their wishes.