Data Stewardship for Non-Personal Data in India

A position paper on data trusts

Summary: Proposing data trusts as ideal stewardship-based governance models for non-personal data.

Background

Data lies at the heart of the modern information society. As we build smart cities, smart homes, and online marketplaces, and digitise public service delivery, otherwise dispersed communities are brought together, and a wealth of information is generated. This information is part of the digital intelligence generated about the systems and the communities, and holds immense potential in improving policy-making and service delivery. Communities are crucial to the process of creating this information, and are the recipients of the impact caused by the data collected. Thus, it is important that governance frameworks reflect community interests in enabling access to this data and safeguarding their interests at the same time.

‘Data Stewardship for Non-Personal Data in India: A Position Paper on Data Trusts’ evaluates this need for community-centric data governance models and proposes data trusts as ideal stewardship-based governance models for non-personal data, i.e. data that does not directly or indirectly identify an individual. A data trust draws on the idea of a legal trust, whereby an asset is held by appointed trustees, and managed by them, for the benefit of individuals or a class of individuals. In the context of data, a data trust serves as a structure for managing non-personal data in the interests of public beneficiaries.

To this end, the paper evaluates the current legal and policy hurdles in operationalising a data trust as a legal trust. It further undertakes a comparative assessment of alternative legal structuring options of registered societies and section 8 or not-for-profit companies, along with public trusts, to highlight the specific concerns associated with each model, and proposes regulatory and policy recommendations to address these concerns. It also proposes a model framework and legislative interventions required to operationalise an ideal data trust.

Objective

The recommendations of the paper intend to provide a regulatory and policy roadmap to set up a stewardship framework for non-personal data for:

- Enabling wider access to such data for the benefit of the community

- Safeguarding the privacy interests of the community

Findings

The assessments undertaken in this paper reveal the following observations:

- Why a stewardship model is ideal: Stewardship of non-personal data can achieve the twin objectives identified above better than current open-data sharing and direct data sharing frameworks which tend to focus on ownership of data. Specifically, stewardship focuses on providing governance schemes for data where it is used and shared, and allows the representation of diverse stakeholders in the governance schemes. On the other hand, ownership-based data governance runs the risk of cordoning off important data sets needed by the community, while open-data sharing does not adequately address group privacy interests.

- Types of stewardship frameworks: An assessment of the variety of data stewardship frameworks geared towards pooling and sharing data – including data exchanges and marketplaces, data cooperatives and data trusts – reveals that data trusts are best-suited for community-centric non-personal data governance. Data exchanges do not provide sufficient opportunities for data users, data providers and the community to participate in the management of data sharing, whereas cooperatives are likely to only partially satisfy the needs of a community-centric data governance framework. On the other hand, data trusts are most likely to activate trust-based and participative data sharing, owing to enforceable fiduciary duties, a charter document that can precisely specify how a data trust will function, and the ability to include stakeholders beyond its members or data providers within its governance decisions.

- Legal framework for a data trust: Upon assessing the legal structures of a section 8 company, a registered society and a public trust, it appears that no single structure currently appears to fulfil each design requirement of a community-focused data trust. This is attributable to the following:

- Data trusts are nascent concepts, which require flexibility within the governing statutes and the associated jurisprudence to accommodate the design choices necessary for a participatory, responsive and accountable data trust.

- The laws governing registered society and public trusts are dated and have not sufficiently evolved to accommodate a data trust. While the structure of registered societies can give rise to competition concerns, the jurisprudence surrounding public trusts does not clearly accommodate data as a subject matter of a trust.

- Section 8 or not-for-profit companies under the Companies Act, 2013 do not provide sufficient mechanisms to allow direct public participation or create enforceable duties owed directly to the public.

- Operationalising a data trust: Operationalising a data trust under the Indian legal set-up, is likely to require some policy and regulatory interventions specifically designed to enable an optimal data trust. This must necessarily be supported by the insights derived from data trust pilots initiated in India in the contexts of data generated by smart cities, educational institutions, hospitals and medical research organisations, etc. These pilots, involving varying combinations of publicly and privately held data, are further necessary for providing insights on the nature of incentives provided by the market, and the scope of regulatory interventions required.

Recommendations for data trusts and government intervention

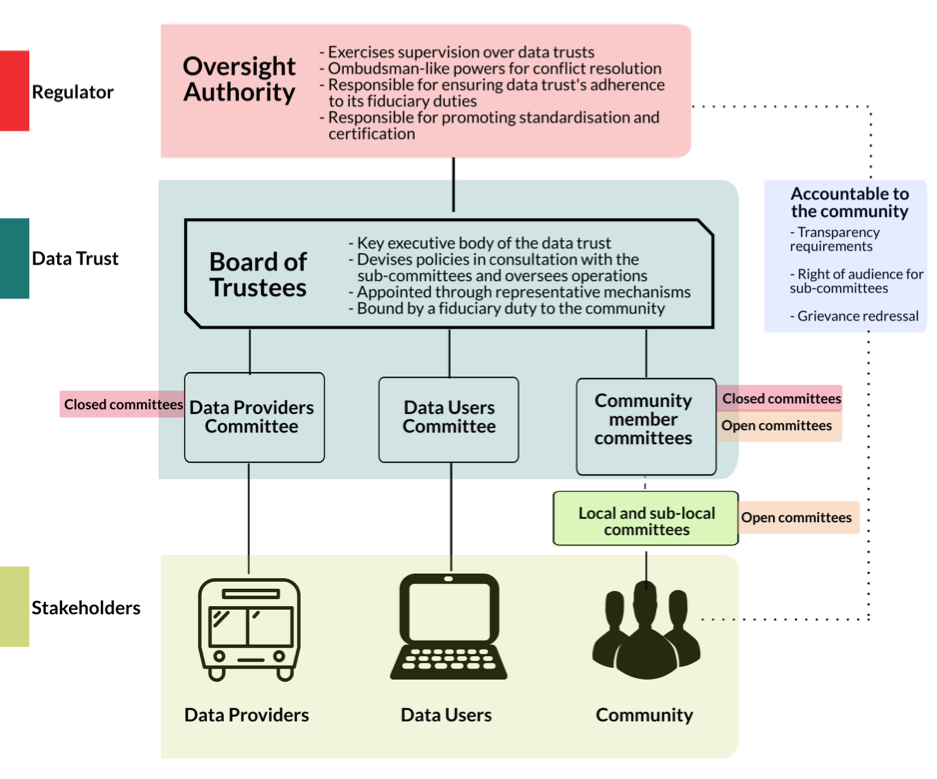

The paper proposes a general structure for a data trust (Figure 1) and outlines specific recommendations. Based on the assessments of various legal structures and associated legal challenges towards operationalising a data trust, as well as existing data stewardship frameworks, a data trust comprising the following is proposed:

- The data trust is managed by a Board of Trustees, which will serve as the executive body of the trust, responsible for devising the overarching policies for data management, access and use, of the trust. The appointment of the Board should be based on a defined eligibility criteria, and may further include nomination by representative sub-committees.

- Sub-committees composed of distinct stakeholder representatives – data providers, data users and community members – are set up to support the Board in formulating policies of the data trust. At the same time, committees with membership open to all community members can enable direct public participation within the management of the trust. These committees may be further federated based on geographic and other divisions.

- The data trust has fiduciary responsibilities at the level of the entity as well as the Board of Trustees, enforceable by general community members, sub-committees, and an oversight body set up for supervising data trusts (further outlined below).

- The data trust is bound by specific transparency and accountability requirements such as public disclosures of policies, annual reports, decision-making, and involves public consultations through local level community-based consultations.

- Resolution of conflicts and grievances is managed at the level of the data trust through online dispute resolution systems, and other accessible systems of reporting and resolving complaints.

- A registration mechanism and a bespoke policy framework, to recognise data trusts as legal entities can validate their legal status based on minimum eligibility criteria. This can help dispel complications associated with amending established legal frameworks for trusts, societies and section 8 companies separately, which extend to highly diverse sectors unrelated to data and information assets.

- An oversight body must therefore be appointed for registering and supervising data trusts. This body should be set up as an independent authority, with its powers and functions clearly outlined. At the same time, the body should be driven by evidence-based decision making and iterative policymaking based on periodic reviews. The body should be responsible, inter alia, for:

- Ensuring that the data trust is performing as per its stated objectives,

- Prescribing transparency requirements such as public disclosures of policies, annual reports etc. of the data trust,

- Enforcing fiduciary duties and other requirements prescribed under any relevant law,

- Promoting standardisation and certification of best practices to be adopted by data trusts through incentive frameworks and certification requirements, and

- Serving as a specialised and transparent avenue for redress of grievances and resolution of conflicts.

- Apart from direct intervention through oversight and registration, the state must also undertake capacity building efforts to ensure informed participation of communities in the data management framework under a data trust and promote the adoption of new technologies that can support data trusts in community-based data governance.

The graph below illustrates a Model Data Trust Framework.

The need for data trust pilots

The following issues are likely to primarily necessitate a study through pilots before arriving at the most appropriate solutions:

- Financial sustainability of the data trust: A data trust may be financed through several avenues, including through stakeholder contributions, state and private grants, revenue generation through its activities, etc. However, accompanying risks of monopolisation of resources, biased decision making and limits to scaling up need to be evaluated for each data trust that is set to be piloted, based on the stakeholders involved, the type of data being stewarded, the available government or private resources, etc.

- Sustainability of the data repository: The nature of the incentives that can ensure a continuous supply of data to the data trust are likely to be better understood through pilots. While a public sector entity may be mandated to share data, private entities and organisations are likely to require specific incentives in the form of tax deductions, waiver of specific conditions in obtaining state licenses and registrations for their respective activities and other such incentives.

- Sector-specific issues: Pilots for specific sectors – such as urban mobility data – can provide experiential insights into the viability and success of data trusts, especially where sector specific challenges are likely to impact their success. For instance, public transit agencies may not be keen on sharing data under data trusts where such sharing requires several levels of government approval, and which is likely to entail a loss in commercial revenues derived from these datasets. At the same time, private entities collecting mobility data may continue to only share their data with public transit agencies on commercial terms. This would also involve negotiating practical rules, conditions and complex relationships between different stakeholders including the city level government departments and central urban development and transportation ministries, along with city level commuters, transit agencies, etc.

An Urban Mobility Data Trust for Delhi

With the objective of studying the practical implications of the proposed data trust framework, Vidhi, in collaboration with IIIT Delhi and Omidyar Network India, will pilot a data trust for urban mobility data. The Urban Mobility Data Trust specifically aims to democratise access to UMD for use by public and private sector entities in developing services in the interest of the public. The Pilot is expected to cover real-time and static data sets comprising scheduling information and real-time location data of buses, and may also expand to include location data for auto-rickshaws. The Pilot is expected to comprise the following main components:

- A Charter laying down the specific objective and duties of the data trust.

- A governance structure consisting of a Board of Trustees and representative sub-committees of stakeholders that can guide the development of internal policies for the governance of the data.

- A technological platform, developed by IIIT Delhi, which hosts the data sets, catalogues them, and enables their secure sharing according to stipulated terms.

- Clear and binding contractual terms to set out the scope of the data licenses, and other obligations to ensure the secure and rights-respecting use of the data.

While the Pilot is currently focused on Delhi, it is expected to expand to other cities within India and provide insights at a pan-India level. These insights will thus be used to fine-tune the recommendations provided within the position paper and propose actionable policy interventions.