Creating Sensitised Communities and Sensory-Friendly Urban Spaces

Accounting for the Vulnerabilities of Persons with Invisible Disabilities

Context

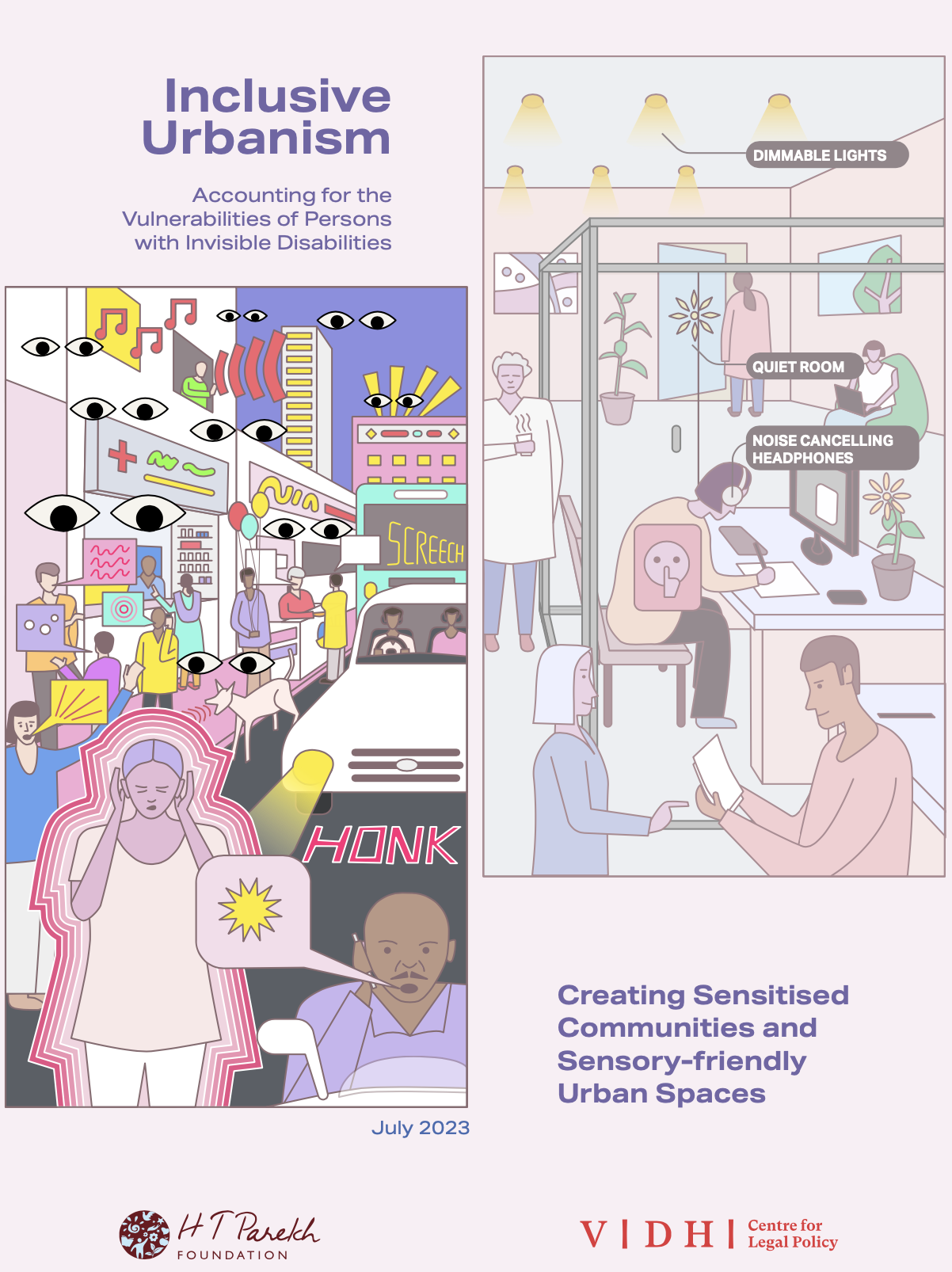

In India, an estimated 17 to 20 Lakh people live with autism, a neuro-developmental condition affecting social interaction, communication, and behaviour. Despite its growing prevalence, modern urban life poses challenges for persons with autism due to difficulties in social interaction, sensory processing, and exclusionary practices. Diagnosis gaps, ignorance, and lack of awareness exacerbate these challenges, especially in policy-making and urban planning. Access, inclusion, and requisite accommodations for persons with autism remain scarce, particularly in loud and over-stimulating cities.

The final paper in the ‘Inclusive Urbanism’ series explores accessibility and livability of cities for persons with autism. It highlights the mismatch between their needs and the overwhelming nature of exclusionary and fast-paced urban environments. Stakeholder consultations provide insights into lived experiences and efforts by parents, caregivers, and advocates to make cities more inclusive. This feeds into the overarching object of the paper, which aims to amplify the voices of persons with autism, their caregivers and advocates and inform policies for better social inclusion and access in urban areas.

Autism and Inclusivity of Urban Spaces

The paper explores the spectrum nature of autism, emphasising the diversity of experiences and rejecting the idea of ‘repairing’ differences. It advocates for respecting individual differences without trying to counteract them. This aligns with the concept of “neurodiversity,” which acknowledges diverse brain structures – particularly that no two people with autism are quite the same. The concept of ‘autism masking’ is discussed, where individuals mimic neurotypical behaviours to fit in, suppressing authentic autistic behaviours. The paper, like other papers in the working paper series, supports the social and human rights model of disability, which focuses on societal barriers rather than impairments, aiming to combat ‘othering’ and promote inclusivity.

Issues: Socio-legal Barriers to Inclusive Urban Spaces

The paper highlights how cities often neglect the needs of persons with autism, placing the burden of inclusion solely on them. It discusses barriers such as stigma, exclusion arising from limited understanding, as well as barriers in built environments like inflexible design, lack of visual signages, and inadequate green spaces, which hinder the accommodation and inclusion of persons with autism. Legal and policy gaps also exacerbate the lack of support systems available to persons with autism and their caregivers. The paper notes how autism did not find any mention amongst the 7 categories of disabilities that were recognised under the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995. It also discusses that despite recognition as a disability under the law, the categorisation of autism was done within the realm of ‘intellectual disability’ under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (‘RPWDA’). It notes further how autism certification has a validity period of certification, in complete ignorance of the lifelong nature of autism.

The paper also highlights the absence of autism-specific policies, with autism-specific measures being dated and introduced largely under the National Trust for the Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act, 1999. It discusses the limitation of ‘benchmarking’ disability based on percentage under the RPWDA, which overlooks autism as a spectrum condition. It also underscores the inadequacy of caregiver support, and highlights the limited Government measures and the unduly heavy reliance on civil society which compounds the already severely prevalent caregiver fatigue and burnout.

Way Forward

The paper offers a set of initial recommendations aimed at fostering inclusivity and support for persons with autism, their caregivers, and the broader community. It stresses the need to address societal, attitudinal, and physical barriers hindering the engagement of persons with autism in urban settings. It advocates for collaboration between stakeholders like governments, local authorities, and civil society to implement training programmes for urban planners, participatory policy planning and large-scale awareness campaigns. Specific measures include inclusive design policies through elements like controlled acoustics, sensory stimuli and visual communication aids for improved navigation, and sensory-sensitive private retreat areas or calm spaces in crowded places, like malls, and railway stations. Caregiver support through community caregiving networks, training programs, and alternative support or “respite care” is also emphasised. Additionally, employment support initiatives, like flexible work schedules, are suggested to help parents balance caregiving responsibilities with other commitments.

Completed in July 2023, this paper is an effort to enhance the sensitivity of urban communities and foster development of sensory-friendly urban spaces. The paper emphasises the lack of discourse on autism in legal and policy domains, underscoring the need for increased understanding to achieve genuine inclusion and transformation of urban spaces. By spotlighting lived experiences, it advocates for a sense of belonging in urban environments.