Realising Community Living in the City for Persons with Intellectual Disability

Context

In India, an estimated 2.6 crore people, with over 1.5 crore under the age of 10, are believed to have intellectual disabilities, though many in this category likely go undiagnosed. Traditionally marginalised and stigmatised, persons with intellectual disabilities have faced exclusion, institutionalisation, and discrimination, all of which have also particularly affected women. Efforts toward deinstitutionalization have aimed to integrate them into broader social settings. This paper advocates for social inclusion and community living of persons with intellectual disabilities, while leveraging provision for the same as found in India’s legal framework, with the aim to enhance access and quality of life for urban individuals with intellectual disabilities. In doing so, the paper outlines the understanding of intellectual disability, advocates for inclusivity through social integration, addresses challenges in realising the right to community living, and proposes recommendations for advancing these goals.

Scope of Intellectual Disability

The term ‘intellectual disability’ is generally understood to refer to deficits in cognitive abilities and adaptive functioning impacting daily life, such as communication, social participation, and independent living. In India, the legal definition places similar emphasis on social and practical skills. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (‘RPWDA’), includes a person with long-term intellectual impairment within the scope of a person with disability. It specifies intellectual disability as consisting of significant limitations in reasoning, problem-solving, and adaptive behaviour. In line with this understanding, this working paper focuses on these social and adaptive aspects to analyse gaps in including individuals with intellectual disabilities in their urban social environment.

Approaches to Foster Social Inclusion and Community Living in Cities

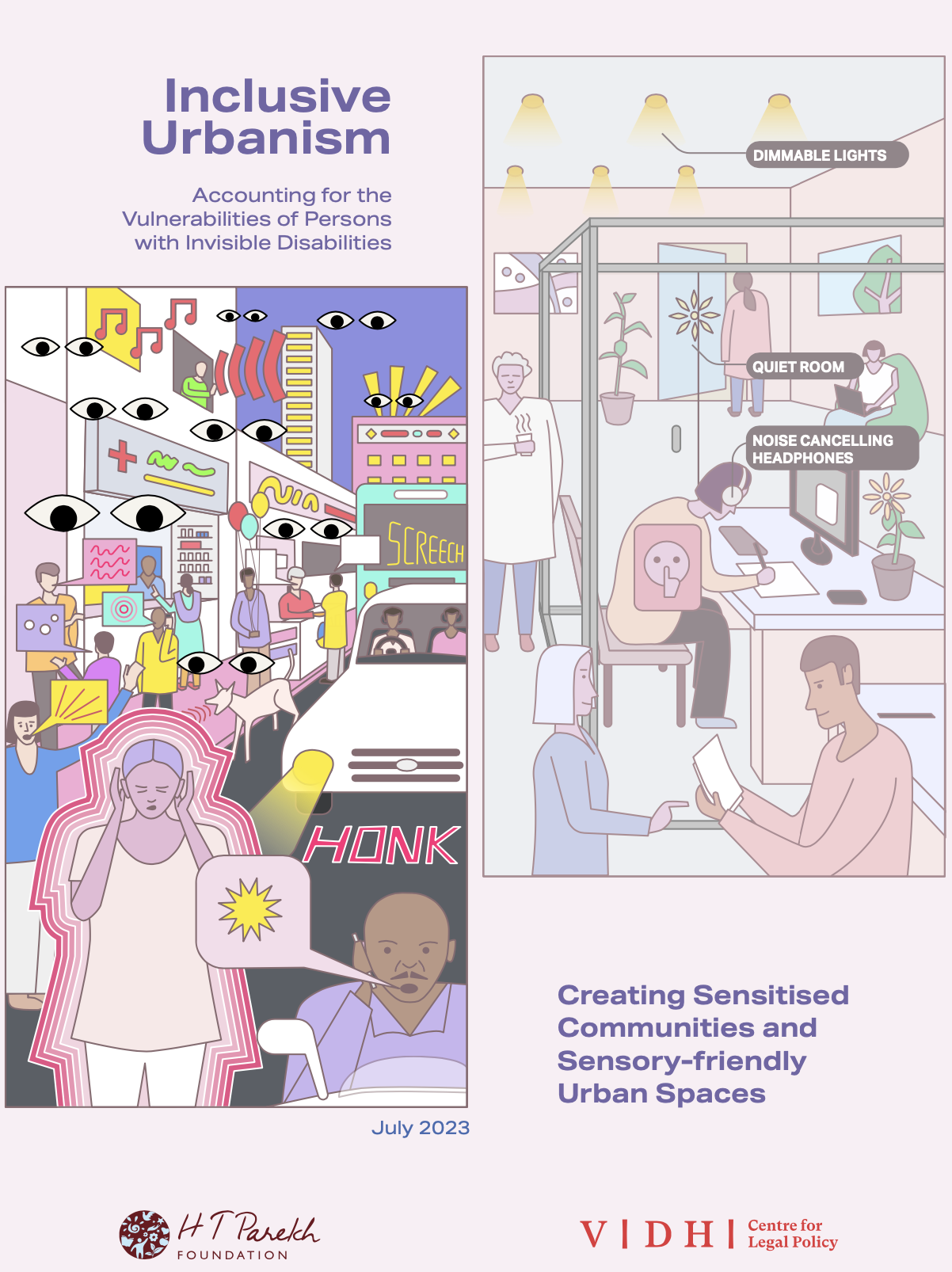

In this context, the paper highlights the need to develop a ‘social dimension’ of access that moves beyond physical dimensions, such that inclusion becomes the collective responsibility of communities at a localised level, through practices that promote daily interactions with community members. It also tries to build conversation on realising the contours of a right to ‘community living’ through which persons with disabilities are able to live in their local communities as equal citizens, with the support they need to participate in everyday life, such as living with their families, going to work, going to school and taking part in social and community activities.

Role of Law and the Current Legal Framework

The working paper initially highlights the strong emphasis on equal social participation and independent community living, as under Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (‘UNCRPD’), which urges states to facilitate the inclusion and integration of persons with disabilities into the community. It highlights this provision as being drafted in response to historical practices of segregation and institutionalisation of persons with disabilities. In India, it details how the National Trust for the Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act, 1999 (‘National Trust Act’), existing for over two decades, aims to empower individuals with disabilities to live independently and close to their communities. However, it showcases how the RPWDA further aligns with the UNCRPD’s broader social inclusion and rights-based approach and in Section 5 explicitly enshrines the right to live in a community.

Issues in realising a Right to Community Living

The working paper outlines key obstacles hindering the establishment of a substantial right to community living in India. Firstly, the provisions on fostering ‘accessibility’ under the RPWDA prioritise physical infrastructure, transportation, and technology – hence, lacking a social dimension, detailing the need for inclusive neighbourhoods, social inclusion schemes, recreation, and caregiving assistance. Secondly, the ‘right to community living’ in the RPWDA lacks implementation and detailing, resulting in a lack of measures to promote this right. For e.g.,in Karnataka, the local implementation of laws and schemes fails to address the segregation of individuals with intellectual disabilities and does not promote equality and agency or programs for community living. Additionally, relevant schemes for intellectual disabilities ((such as the Gharaunda, Samarth and Sahyogi schemes providing for group homes and community and personnel based care), often operate under the older National Trust Act, lacking data-based evaluations of family or community-based efforts under the current regime. The paper also emphasises the pervasive marginalisation and exclusion caused by stigma, urging efforts to change stigmatising terminology, especially within the NTA, which still defines and uses the term ‘mental retardation.’

Way Forward: Developing a Right to Community Living

The working paper aims to enhance the understanding of the right to community living and improve urban accessibility for individuals with intellectual disabilities. It suggests supplementing existing legal standards with measures promoting higher social inclusion in urban spaces, involving community members in various aspects like volunteer work, art, sports, and group activities. The paper advocates moving beyond institutionalisation to focus on identifying local social spaces for meaningful interaction, such as social programs for leisure and recreation. Additionally, it emphasises developing human infrastructure to provide routine assistance to individuals with disabilities, alleviating the burden on family members or caregivers. Lastly, the paper recommends investing in awareness campaigns and sensitization programs at all levels of government and in various sectors to promote acceptance and understanding of disabilities.

Completed in July 2023, this paper tries to reimagine accessibility and inclusion from this lens of a ‘right to community living’ in order to promote the inclusion of persons with intellectual disabilities – and shift their predicament from institutionalisation to community living.