The Decriminalisation Conversation Needs to go Beyond Ease of Doing Business

Summary decriminalisation efforts no cure to make Indian laws more responsible.

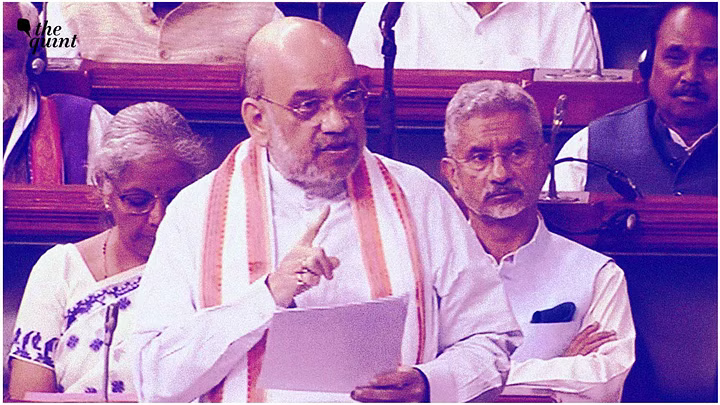

The Union Minister of Industry and Commerce recently introduced the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of Provisions) Bill, 2022 (‘Bill’). Aiming to enhance ‘trust based governance for ease of living and doing business’, the Bill proposes to decriminalise minor offences and rationalise punishments under 42 central laws. Covering a total of 183 provisions, the Bill is the Government of India’s big push towards making India investor and business friendly.

The Bill is a step in the right direction to achieve its stated objective of shedding ‘the baggage of antiquated laws’ affecting India’s developmental trajectory. It may also be successful in convincing businesses and investors to invest in India. However, it does not have the potential to ‘unshackle the bygone mindset’ in this purported Amrit Kaal of independent India.

A narrow view of overcriminalisation

Firstly, because of the focus on ease of doing business, the Bill barely makes a dent in the landscape of laws that use criminal provisions for compliance. It also leads to a narrow understanding of the issue of arbitrary and over criminalisation, confronting India’s criminal justice system.

There are approximately 400 central laws that have criminal provisions. Many of these laws criminalise and provide jail terms for mere non-compliance of procedures or trivial acts/omissions. Many laws, however, do not define the criminalised acts clearly, a necessary prerequisite for a criminal law. For instance, Under the Police Act, 1861, committing cowardice is punishable by up to 3 months of imprisonment. The law, however, does not define what ‘cowardice’ is.

Some of these laws also provide disproportionate punishments. For example, under the Indian Tolls Act, 1851, demanding a higher toll than lawfully authorised can attract up to 6 months imprisonment. Causing hurt by an act which endangers human life also attracts the same punishment under the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Similarly, in many laws punishments are arbitrary and bear no clear nexus with the object of these laws. For instance, failure to facilitate inspection of vessels under the Inland Vessels Act, 2021 can attract up to 3 years of imprisonment. On the other hand, under the IPC, adulterating medical preparations can attract only up to 6 months of imprisonment.

In the way of rationalising penalties

Secondly, even though the Bill claims to rationalise penalties, it fails in doing so. For example, in the Rubber Act, 1947, the Bill proposes to decriminalise furnishing a false report; obstructing any officer; or failing to produce records before an authorised officer. Similar violations can be found in many other laws, such as the Central Silk Board Act, 1948, the Inland Vessels Act, 2021 and the Code on Social Security, 2020. These, however, have escaped the government’s attention and continue to provide for jail terms ranging from 6 months to 3 years.

Further, under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, the Bill proposes to remove imprisonment for the subsequent offence of ‘using a government analyst’s report for advertising’. It also proposes to make the offences of manufacturing, selling or distributing drugs in contravention of the law, compoundable. A rather serious act, which may at times endanger human lives.

In the same law, ‘failure to maintain records and registers’, can attract a jail term of up to 1 year. Manufacture or sale of otherwise unadulterated drugs, in violation of the law, may attract a mandatory minimum sentence of 1 year, the same as one can get for a more serious offence of manufacturing or selling spurious ayurvedic, siddha or unani drugs. This arbitrariness in the prescription of punishment, has again escaped the government’s attention.

Can a summary decriminalisation exercise really help?

The Bill is a bold attempt at saving state resources. But some of these violations may still have to be reported to the police and tried by criminal courts, some will require administrative procedures to take over. Whether they save time, energy and resources, only time will tell.

The Bill could also be an attempt towards reducing incarceration – the only catch is that hardly anyone goes to prison under provisions that the Bill touches. Data from the National Crime Record Bureau shows that most people in prisons, whether undertrial or convicts, are for offences of murder, attempt to murder, rape, theft etc.

As we continue to rely on a criminal justice response to social and regulatory issues, and use criminal law to shape public behaviour, freeing ourselves from the colonial mindset seems to be a distant dream. More so with the decriminalisation conversation being undermined by the ease of doing business push. Independent India’s Amrit Kaal will not arrive unless the government’s outlook towards its citizens changes. Changing India’s criminal law making practices is critical to this. A summary decriminalisation exercise must not replace a sustained effort to make India’s criminal law making practices more responsible, informed and principled.