No Force to Enforce: Story of Consumer Commissions and Their Orders

Consumer Commissions need structural reforms to ensure justice

Consumer Disputes Redressal Commissions (Consumer Commissions), a quasi-judicial body, was established in 1988 under the Consumer Protection Act of 1986, to provide speedy and accessible justice to consumers against malpractices, and to reduce the burden on traditional court systems. However, even as its establishment has expedited the process of delivering judgments and disposal of cases, roadblocks remain in the execution of these judgments. As a result, even after years of litigation in the fight for a favourable order, justice remains elusive for consumers. Even applications filed by consumers to speed up the execution of orders (Execution Applications) remain undisposed by these bodies.

Vidhi’s ongoing research to study the efficiency of the District Consumer Disputes Commissions in Bengaluru and the Karnataka State Consumer Disputes Commission finds that as of July 2018, three out of five District Consumer Commissions in the Bengaluru Urban District were unable to dispose even 50 percent of the Execution Applications filed in 2013.

On the other hand, between 2013 and 2017, the number of Execution Applications filed in both Bengaluru and Karnataka Commissions increased by 287 percent – from 310 in 2013 to 891 in 2017.

This piece explains the reasons for the inefficient execution of judgments by Consumer Commissions, and gives recommendations.

Current structure fails to check if Commissions’ orders are obeyed

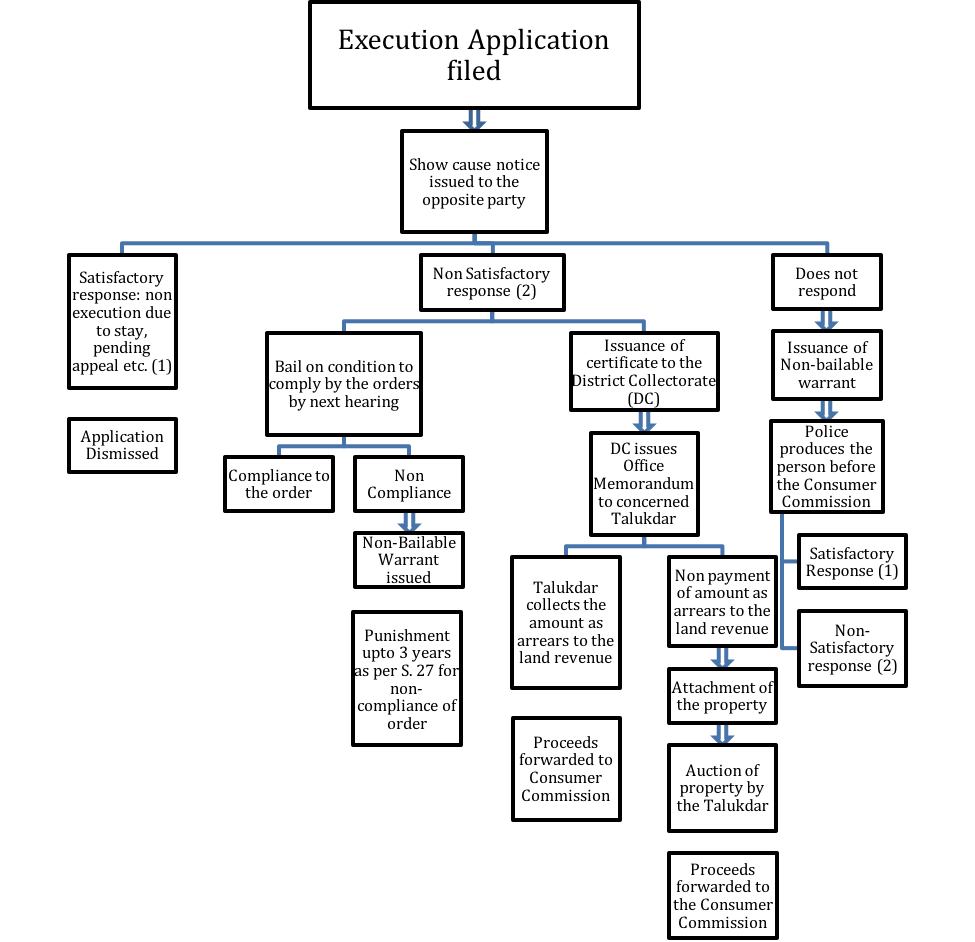

Section 25 of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 empowers the Consumer Commissions to enforce their orders by attaching and auctioning the property of the person not complying with the order. Commissions can recover the amount from the auction to execute their order and make the payment to the aggrieved party. Commissions can also issue a certificate to District Collector to recover the amount due in the same manner as arrears of land revenue. The chart below explains the procedure of execution of orders by Consumer Commissions, as applicable in Karnataka.

However, as the chart details, the current structure requires Commissions to involve the District Collectorate to collect the amount that go as proceeds to the Commission. This is because there is no provision under the 1986 Act and the rules formulated under the Act for an officer to exercise executions powers, unlike in civil courts where a bailiff is empowered to make sure decisions of the court are obeyed.

However, as the chart details, the current structure requires Commissions to involve the District Collectorate to collect the amount that go as proceeds to the Commission. This is because there is no provision under the 1986 Act and the rules formulated under the Act for an officer to exercise executions powers, unlike in civil courts where a bailiff is empowered to make sure decisions of the court are obeyed.

The Commissions’ dependency on the District Administration for execution leads to a complex and opaque procedure. Further, the District Administration, already burdened by other functions, often neglects this job which results in the delays.

New Act marks no change

The Consumer Protection Act, 2019, which repeals the 1986 Act, aims to expand the scope of grievances consumers can complain against and ease the process of filing complaints. However, it fails to achieve better execution of orders by Consumer Commissions. Here’s how:

• The Act, which hasn’t come into force yet, does not specify rules for appointment of staff for execution of orders, hence, marks no change from the 1986 Act. Consumer Commissions will still likely have to depend on the District Administration for execution.

• The 2019 Act allows Consumer Commissions to detain those not complying with orders in civil prisons, attach their immovable property, agricultural crops, etc. In doing so, it increases the powers of Consumer Commissions to match with those of civil courts. However, without any change in the Commissions’ structure, this will go on to only increase the burden on the District Administration.

Additionally, complexities for consumers could also increase if more procedures similar to that of a civil court are introduced. As a result, it could reduce accessibility of Consumer Commissions, defeating the whole purpose for which they were set up.

Changes required

A three-pronged solution to combat the problem of execution is required, as explained below:

1. A simplified procedure to execute orders with lesser interaction with external authorities should be adopted by the Consumer Commission. Specific rules should be framed to this end.

2. The Union and State Governments should provide for the appointment of execution officers or bailiffs in every Consumer Commission. The execution officer should be provided with the function and powers to carry the enforcement of orders.

3. Specific guidelines for the functioning of such officers should be issued to ensure transparency of process.

Increasing the capacity of the Consumer Commissions, simplifying the execution procedure, and increasing transparency will go a long way in ensuring efficient enforcement of orders, thus truly giving power to ordinary people seeking justice against business wrongdoings.

Views are personal.