Is a Central Examination Process a Silver Bullet for Filling Judicial Vacancies?

An All India Judicial Services (AIJS) examination likely to add to judiciary’s troubles

The All India Judicial Services (AIJS) is an idea which has been around since 1954 to centralise the examination process for district level judiciary only, much like the Indian Administrative Service. While it has been opposed by High Courts and state governments over the years, the union government has recently rolled out its latest plan to implement this by March 2022.

A key rationale behind introducing the AIJS is to fill up judicial vacancies through opening it up via a central examination, and making it more attractive for potential applicants. It is also argued that pendency in cases is due to the vacancy of judges in the system. If this were to go through, it would be a substantial change to the judicial system, and would centralise power in the union government’s hands to appoint district level judges, who are currently recruited by high courts along with state governments. Given that the district judiciary is right below the high courts, it wields considerable power in the adjudicatory process.

This piece argues that the core rationale mentioned above, and other reasons argued in favour of AIJS, are erroneous, and for this Vidhi has relied on details in newspaper reports since the proposal is not in the public domain as yet, although an RTI has been filed with the law ministry. Further, Vidhi’s December 2019 report ‘A primer on the All India Judicial Service – A solution in search of a problem?’ examines this issue in detail.

Arguments against the creation of an AIJS

Judicial vacancies are unique to each state: Vacancies have erroneously been hailed as the only cause behind massive pendency and delays in Indian judiciary. An AIJS may not only fail to address the issue of vacancies adequately, but may create more problems for the judiciary. Here is why.

According to the Supreme Court’s 2018-19 annual report, vacancies across states are not uniform. Uttar Pradesh has the highest vacancy in the country contributing to 27.58% of overall vacancy, followed by Bihar at 13.05%. Thirteen states contribute to less than 1.5% of the overall vacancy. Based on our previous studies, the reasons for these vacancies could be varied and could range from complicated recruitment processes to the lack of adequate court rooms.

In fact, in a case before the Supreme Court on the issue of vacancies, the Allahabad High Court has filed an affidavit stating that they lacked courtrooms to house additional judges. Therefore, judicial vacancy is not an issue that can be immediately addressed via a central examination but is a problem unique to each state.

Importantly, the AIJS excludes the range of subordinate judiciary (below the district judiciary) – often the first point of contact for most litigants in the country – which is a potential site for delay and vacancies. Hence the argument of an AIJS reducing vacancy stands on weak ground per se, given it’s only applicable to district judges.

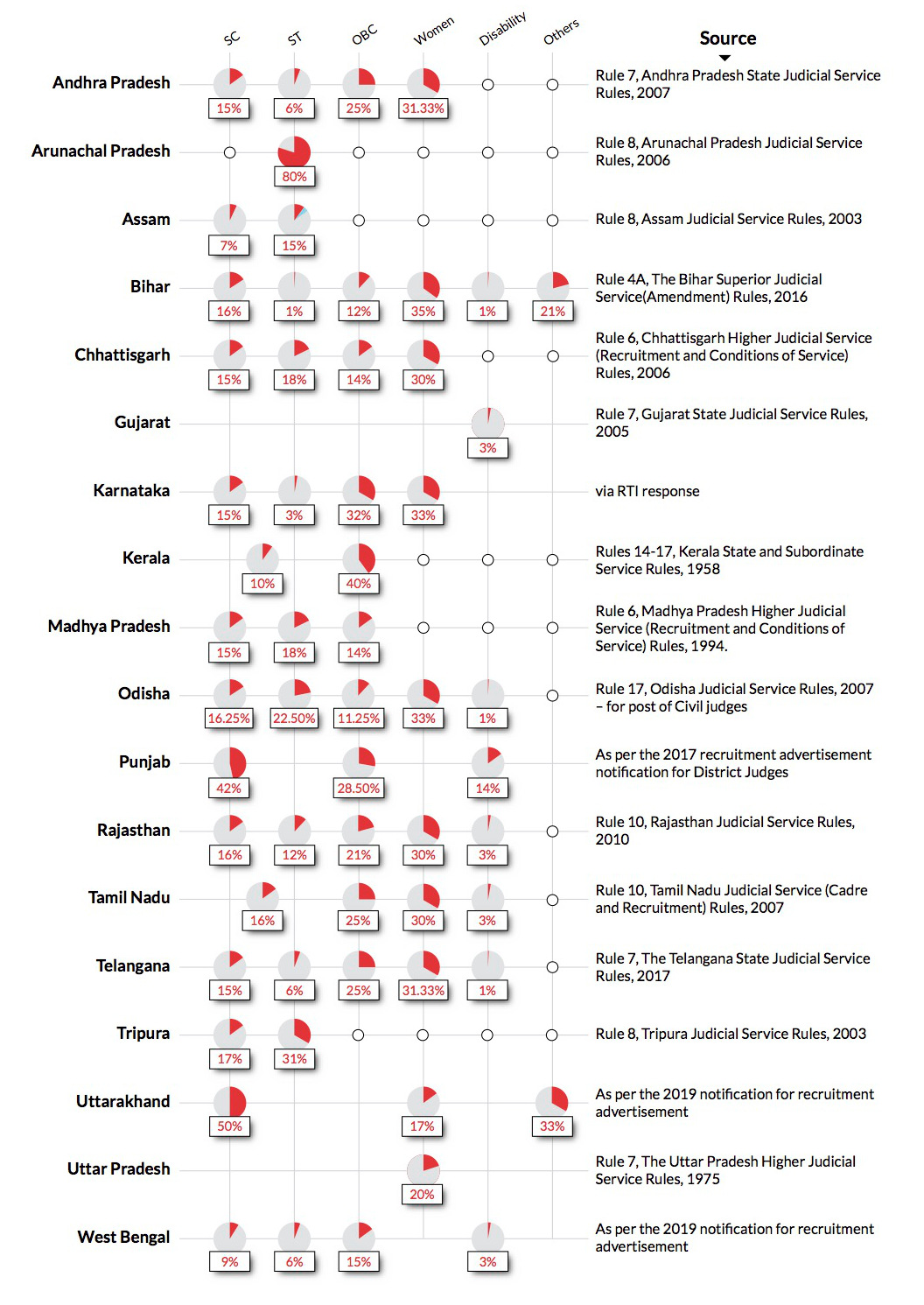

No solution for equal representation: The latest plan for an AIJS provides for 25% reservation for Other Backward Classes (OBC), Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). The AIJS was presented by the law minister as a solution to address “social inclusion by enabling suitable representation to marginalised and deprived sections of society”. However, most, if not all, states already provide for reservations for people from OBC, SC and ST, but also for women (who are not covered for reservations in any centralised examination) and persons with disabilities.

The infographic below shows the extent of reservation currently being given by different states to different sections of marginalised communities.

Hence, claims that an AIJS will remedy the lack of representation for marginalised communities are inaccurate. In fact, many communities may oppose the creation of an AIJS because the communities recognised as OBC by state governments may or may not be similarly classified by the central government.

Hence, claims that an AIJS will remedy the lack of representation for marginalised communities are inaccurate. In fact, many communities may oppose the creation of an AIJS because the communities recognised as OBC by state governments may or may not be similarly classified by the central government.

An AIJS may threaten the independence of the judiciary: The proposed AIJS provides for an oversight committee headed by a Supreme Court judge to set the examination and syllabus. High court judges, legal academicians and a representative of the UPSC (Union Public Service Commission) will also be part of it. However, there is no clarity on whether this committee will transform into a body determining terms and conditions of service, including transfer and removal, or will that continue to be as per state rules. The questions that arise here are:

If state rules are to govern the terms and conditions, is taking away the power to recruit and appoint against the principle of federalism and basic structure doctrine?

On the other hand, if a central body is to determine the service conditions, will that stand the test of constitutionality?

These questions strike at the root of independence of the judiciary. They also create uncertainty around the process which might deter potential candidates from applying to the district judiciary.

Judges recruited through an AIJS will not know the local languages of the states: The knowledge of local language and customs is important for district judges to read evidence, understand arguments, and to make accurate interpretations before making decisions that affect life, liberty and property of people. Judges recruited through an AIJS may not know the local languages of the state and training given for the same is insufficient.

A holistic approach is required

The additional funds required to implement an AIJS and for the two-year training for judges thereafter can instead be utilised towards implementing other solutions that can significantly reduce delay such as improving poor court infrastructure, adopting technological interventions, or appointing court managers.

Attempts to create an AIJS have failed due to lack of clarity and nuance in proposals. This time around, confusions around the idea of an AIJS need to be addressed better so that states can evaluate whether the process will help unburden the judiciary or add to its troubles.

Views are personal.