Higher Administration in India and the Woes of Central Deputation

The All-India Services (AIS) received some attention in 2021 when a tussle ensued between the centre and the West Bengal government over the deputation of Alapan Bandopadhyay, an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer from the 1987 batch. In 2022, owing to proposed amendments concerning the rules regulating the central deputation of officers, the AIS have come into sharper focus. The proposed amendments, the states assert, seek to take away the power of states to veto the centre’s request seeking officers for deputation, and run against the spirit of cooperative federalism.

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), through a letter dated 20th December 2021, wrote to the states seeking their opinion on the proposed amendment to Rule 6(1) of the IAS (Cadre) Rules, 1954. Rule 6(1) concerns the central deputation of IAS officers. States’ opinions have also been sought on similar amendments to the Indian Police Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954 and the Indian Forest Service (Cadre) Rules, 1966, by the respective cadre controlling authorities. By way of these amendments, the centre proposes to gain greater control over the deputation of officers, primarily because of the shortage of AIS personnel at the centre owing to the alleged disregard by states of their obligations towards the Central Deputation Reserve (CDR).

This post explains the rules of the game concerning the deputation of AIS personnel. Keeping in view the implications of this tussle for Indian federalism, it asserts that only a consultative approach in deputing officers at the centre from state cadres is consistent with India’s federal set-up.

What are the All-India Services?

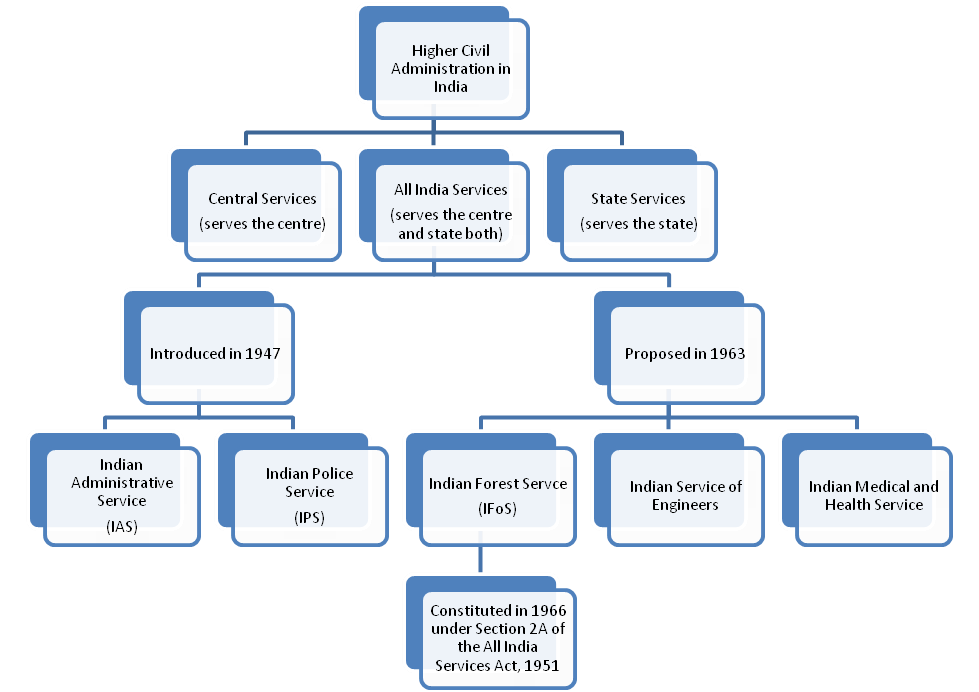

Administrative services in India can be grouped into three categories – the Central Civil Services serving the centre (for example, the Indian Foreign Services, Indian Postal Service, etc), the State Civil Services dealing with state related issues, including services of personnel like Sub-Divisional Magistrates, Block Development Officer, Land Acquisition Collector, etc, and the AIS which serve both the centre and the states.

At the cusp of Independence, India retained two civil services: the Central Service and the AIS. The AIS is a unique cadre of administrative officers common to the centre and the states, recruited and controlled by the Government of India. Vallabhbhai Patel, as the Home Minister of the interim government, advanced the central government’s decision to build a unified AIS as a bridge between the centre and the states. He convened a Conference of Provincial Premiersin October 1946 wherein the question concerning the control over AIS was discussed at length. Despite initial opposition from provincial governments, the creation of the AIS was approved. As a result, in independent India, the AIS comprised the IAS and the Indian Police Service (IPS).

In 1950, the AIS gained constitutional recognition under Article 312 and became the subject of the centre’s exclusive jurisdiction under List I Entry 70 of the Seventh Schedule. In 1963, through an amendment to the All-India Services Act, 1951(1951 Act),provisions were made under Section 2A for three more AIS: the Indian Forest Service (IFoS), Indian Service of Engineers, and the Indian Medical and Health Service. The IFoS was constituted in July 1966, whereas the two other proposed services were shelved owing to sustained state resistance for want of greater control (over these services).

Structure of Higher Administration in India

The AIS was envisaged to create a shared pool of centrally recruited administrative personnel for the centre and the states to strengthen the unitary character of the Indian federation. The officers of the AIS are governed by the 1951 Act, which regulates their recruitment and conditions of service. Section 3 of the Act authorises the centre to make rules in consultation with the state governments. Each time the centre proposes to introduce a new rule or amends an existing rule, the State governments are to be consulted for their opinion. Given that the centre is expected to only consult and not obtain states’ concurrence, it may appear that the Centre is free to frame rules even with states’ opposition or omission to reply. However, convention warrants a cooperative and collaborative approach between the centre and states when framing rules concerning the AIS.

Recruitment and Allotment of Cadre

Recruitment to the AIS is through a centralised and independent Civil Service Examination conducted by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC). The centre, in consultation with the states, carries out a “cadre review” wherein the state-specific requirement of new officers in each service is assessed. Based on this assessment,recruitment is done by the UPSC. Finally, the officers are appointed by the President, thus making the central government the appointing authority.

Immediately after appointment, the cadre allotment procedure is carried out. AIS cadre allotment is managed by the centre through three cadre-controlling authorities – DoPT for the IAS, Ministry of Home Affairs for the IPS, and Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change for the IFoS. As per the cadre allocation policy (2017), allocation is done on the basis of officers’ merit, preference, and vacancies in the state cadre.

To maintain the all-India character of the services and to instil in them a national vision, AIS personnel undergo centralised training. Initially, joint training is conducted at the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA), Mussoorie. While the IAS are trained fully at the LBSNAA, the IPS and IFoS are trained further at the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Police Academy (Hyderabad) and the Indira Gandhi National Forest Academy (Dehradun), respectively.

Post-training, AIS officers are allocated to respective state governments with an occasional deputation to the centre. At this point, states enjoy exclusive power over the posting, promotion, and transfer of officers from one district to another within the state.

How does deputation work?

Central or State deputation of AIS officers from state cadres is regulated by Rule 6 of the IAS (Cadre) Rules, the IPS (Cadre) Rules, and the IFoS (Cadre) Rules. The central government fixes the share of officers that can be made available to the Government of India out of the state cadres – this is known as the Central Deputation Reserve. In practice, officers who have served the state government for a minimum of nine years may offer themselves for central deputation through the state government. Every year an ‘offer list’ of officers willing to go on central deputation is prepared, from which the centre hand-picks. On selection, the state relieves such officer(s) for deputation. Thus, an AIS officer is available for central/state deputation through a tripartite consultative process involving the centre, the state, and the officer. In the case of disagreement between the centre and the concerned state, the decision made by the centre prevails.

Most of the administrative officers appointed by the centre (as part of the AIS) are allocated to state cadres. Whenever the centre needs senior-level personnel in planning, policy formulation, and implementation of programmes, officers from the AIS are called for central deputation. These personnel return to their respective cadres at the end of their deputation tenure. Deputation of AIS officers at crucial positions in central administration is preferred due to the localised field experience they bring to the centre. Also, this practice ensures that each level of government gets an insight into others’ constraints and concerns, thereby ensuring healthy equilibrium in a federal system.

Proposed amendments and the controversy

The central government has proposed four amendments to Rule 6(1), by insertion of certain provisos and modification of existing ones. Essentially, the amendments:

- Require every state government to offer for central deputation a fixed number of officers every year. It empowers the centre to decide the actual number of officers to be deputed to the central government, in consultation with the states concerned;

- However, in case of any disagreement on deputation of cadre officers between the centre and the state, the state government concerned shall be obliged to give effect to the decision of central government “within a specified time”;

- Require the State government to release such officers whose services may be sought by the Central Government in certain “specific situations”;

- Necessitate that an officer approved for central deputation shall be relieved from the state cadre on the date decided by the centre. The requirement of a no-objection certificate from the state government in this regard has been dispensed with.

While proposing these amendments, the centre has cited the non-availability of officers (at the central level) which has been affecting the functioning of the government. Data suggests a trend of fewer officers coming to the centre on deputation, in an indication of states not adhering to their CDR obligations. The number of officers forming part of the CDR has reduced, and so has utilisation of the CDR.

States have opposed these amendments over apprehensions regarding loss of further autonomy on the issue of deputation, when the rules presently are anyway tilted in favour of the centre. Utilisation of the AIS deputation reserve by both the centre and states presupposes “consultation” between the two. It is this aspect of consultation that the top-down imposition of rules seems to be doing away with. Allusions to the notification of these rules in the Official Gazette in case of failure of the states to respond does nothing to allay the states’ apprehensions.

A top-down imposition of these proposed changes by the centre will run contrary to both the conventions as well as the scheme of the 1951 Act which presupposes centre-state consultation for matters concerning the recruitment and conditions of service of AIS officers. States have an independent constitutional existence and they are not agents of the centre. Any haste on the part of the centre to bring these rules into effect will create distrust between the two tiers of government besides raising concerns about the independence of the AIS officers themselves.

Views are personal.