Can Artificial Intelligence Improve Tax Assessment in India?

The need for defined parameters for AI to operate in tax

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and automated tools in tax administration has seen rapid growth. Right from when a taxpayer files their income-tax returns till the assessment of a taxpayer is concluded, multiple automated tools are employed by tax authorities at different stages. These automated tools are designed to perform functions that were conventionally performed by tax officials including adjudication.

The policy rationale behind the use of automated tools is to bring about consistency within the tax regime and eliminate discretion that can creep in with human intervention.

This gives rise to some novel legal questions: Are these tools capable of replacing tax officials? If yes, to what extent? This pieces looks at the creases that need ironing in the AI tax assessment system.

Where do automated tools fit in the process of tax administration?

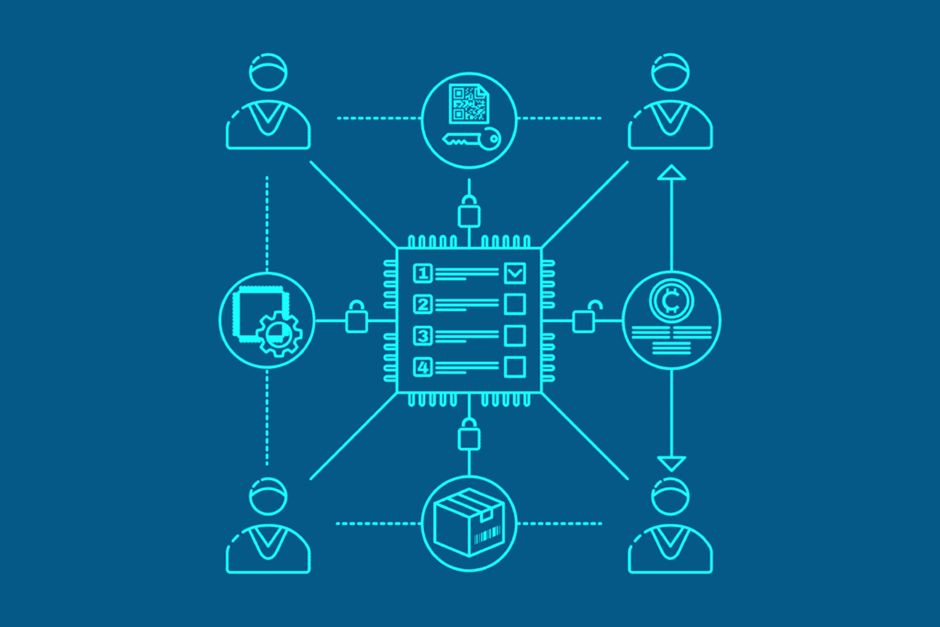

Stage 1: The returns filed by taxpayers are processed using a software which acts as the first filter to weed out incorrect claims in the returns furnished by taxpayers.

Stage 2: Doubtful income-tax returns are selected for assessment. This exercise is either done manually or by way of an automated tool known as CASS (computer-assisted scrutiny selection) which selects cases after conducting a 360-degree risk profiling of a taxpayer.

Stage 3: An automated allocation tool is used to assign the cases selected for scrutiny to the assessment unit.

Stage 4: When a draft order has been finalised by the assessment unit, an automated examination tool is employed which decides if the draft order will be finalised or will undergo review, or if the taxpayer’s perspective will be heard – based on a risk management strategy adopted by the department – before the order is finally communicated to the taxpayer.

Challenges imposed by the use of technology

• Certain steps need human intervention: Technology alone cannot perform the task of administration or adjudication without any human intervention. This recent case is an example:

A tax official had relied on the conclusion arrived at by automated tools under stage 1 to pass a final assessment order which was erroneous. The Madras High Court explicitly recognised that while the Income Tax Department’s move to pave way for an objective faceless assessment without human interaction by employing technology was laudable, such proceedings can lead to erroneous assessment. Hence, they must bear corroborative value only after affording taxpayers a personal hearing to explain their case.

• Lack of defined parameters for technology to operate: While the use of automated tools is likely to cater to achieving consistency in tax administration, a lack of defined parameters in the public domain for automated tools to produce an output opens up the use of technology to future legal challenges on the grounds of arbitrariness.

For instance, what constitutes a ‘360 degree profiling’ (stage 2) before a case is selected for scrutiny is known only to the tax department. The algorithm used for assigning cases to assessment centres is also not known. What constitutes a risk management strategy based on which the fate of draft orders is decided is not known to a taxpayer either. The algorithms themselves are open to challenge on the grounds of arbitrariness if they are based on incorrect parameters or are ignorant of certain nuances.

An example from the US

Multiple cases in the US have questioned the sanctity of the use of automated tools for administrative and judicial functions. Several courts in the US have upheld the validity of employing such automated tools in discharge of administrative/judicial functions. However, their decision is based on the fact that such tools have defined algorithms/parameters that are available in the public domain, and that the outcome of the employment of such tools holds only corroborative value which may be disregarded by humans while rendering a final decision.

Thus, in the US, defined parameters and necessary human intervention at a subsequent stage act as pre-requisites for any automated tool employed for administration and adjudication to pass judicial scrutiny.

The US Supreme Court has identified the issue as a contentious one, but has chosen not to intervene at this stage. In choosing to do so, it considered the argument of the Solicitor General’s Office that no division of authority yet existed on the validity of the use of these algorithms and that the issues raised in the petition would benefit from further percolation amongst the lower courts.

Way forward

The Income Tax Department can start by making the parameters publicly available. Especially given that the availability of guidelines in the public domain has been the basis for upholding the use of algorithms in administration and adjudication in other jurisdictions like the US. This move will bolster public confidence in the use of technology to perform administrative and adjudicatory functions.

Views are personal.