App Stores and Cracks in the ‘Walled Garden’ Approach

Regulating app stores requires a nuanced, experimental & precise approach

The past few months have seen app stores being propelled to the forefront of public imagination – for instance, the Congressional antitrust hearings of the ‘big four’ tech companies in the United States, which discussed app stores in detail, were a global event. The Fortnite-Apple dispute over the ‘apple tax’ charged by Apple for in-app purchases made on apps available on its App Store also played out in the public eye.

Closer home, around 56 founders in the Indian startup ecosystem, collectively made a representation to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) in relation to changes that Google was considering to its Play Store which would require all apps to route their revenues through the Google Play Store and pay a 30% fee to Google. While Google deferred its decision to enforce these changes in India, the debate about the role of app stores remains relevant for the future of internet governance.

Conceptualising app stores

Concept of the ‘walled garden’ approach: The proposed changes to the Google Play Store would have brought its model of operation closer to Apple’s App Store, its main competitor. Apple has set up a much more tightly controlled mobile environment.

The Apple App Store requires apps to be individually reviewed for content and security, and like the proposed Play Store changes, requires all in-app purchases to be routed through the App Store where it charges a 30% fee. The convergence between two mobile environments (Android & iOS) with arguably opposing philosophies points to a greater recasting of the role of app stores.

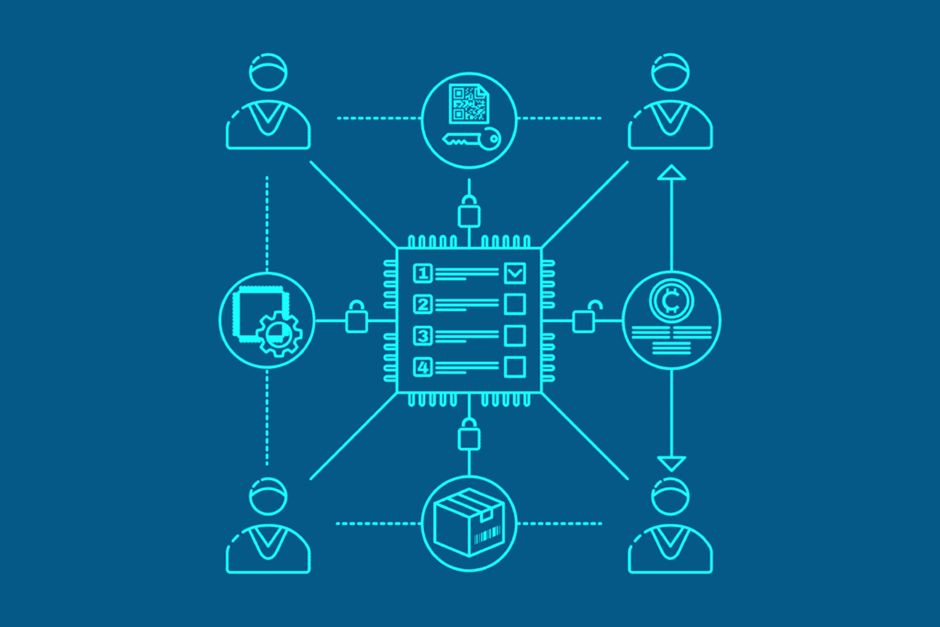

The need to develop trustworthy mobile app environments is perhaps the driving force behind this convergence. This approach – famously cast as the ‘walled garden’ approach – requires third-party developers to adhere to guidelines related to content, security and review of apps before they can be listed on the app store. The idea is to create a trusted marketplace where users can freely navigate and explore high quality apps and make payments without fear of malware.

Potential impact of ‘walled garden’ approach on third party developers: Some commentators note that the idea of creating a trusted environment will prevail despite opposition from third-party developers to the recently proposed changes, who complain that the ‘fees’ would be a crippling blow for their industry. This is premised on the idea that benefits of the Google Play Store would offer incentives for developers to not abandon it in favour of other less popular app stores available in the Android ecosystem. This view rests also on the near-duopoly status enjoyed by the App Store and the Play Store in their mobile environments, where the number of users who rely on these stores makes them an inevitable partner for a third-party developer who wants to reach a meaningful audience.

Competition law measures may be necessary to ensure that third-party developers do not face a market which has crumbled from market failure and the opt-in to the ‘walled garden’ is the only way to access the market for their apps.

App stores as ‘platforms’: While app stores deliberate policies about the extent of control they will exercise, they essentially operate as ‘platforms’ – their stated function is to connect a third-party app developer to a user. Legally, the ‘platform’ or ‘intermediary’ status of app stores has provided them with an exemption from liability for third-party content in several jurisdictions, including in India where they may be classified as ‘intermediaries’ under the Information Technology Act, 2000. Therefore, at the core of the ‘walled garden’ of digital platforms is still a stage – where the app store is just a middleman between the app developer and the user, and where it only accepts the responsibility of an intermediary.

App stores as ‘utility’: A third conceptualisation would cast app stores in the overarching role of an ‘utility’ or an ‘infrastructure’ . This is based on the idea that app stores effectively perform what may be termed a ‘public function’, and therefore, should be imposed with duties that prevent discrimination, require ‘app neutrality’ and require procedural and substantive due process for decisions taken by the app store. This view is perhaps further strengthened by the evident duopoly in mobile environments, and the fact that the App Store and the Play Store both occupy a critical position in letting users navigate these environments, therefore de facto being the only means through which third-party apps are made available to users.

Reconciling the ‘walled garden’, the ‘stage’ and the ‘utility’

This brief discussion points to the following implications: first, app stores are platforms which offer a ‘stage’ for users to connect with third-party developers; second, they are also ‘walled gardens’ which require adherence to guidelines and rules related to content, security and reviewing to build trust in the mobile environment; finally, they are also utilities which are critical to letting users navigate their mobile environments.

This complexity is particularly relevant since it would determine the legal approach adopted to regulate app stores. As witnessed in the ban on various Chinese applications in India as well as the TikTok ban in the United States, app stores occupy a critical position in the enforcement of laws online. The central role of a few app stores in enabling access to applications has also rendered them a single-point-of-failure in internet governance, where the app stores’ policies on content takedowns and compliance with law enforcement requests can be determinative of access to an application. An approach of regulating app stores must consider these dimensions before it can offer a viable solution for promotion of the public good.

Most importantly, any regulatory approach must consider the fact that platforms – such as app stores, as well as other platforms like e-commerce platforms – are very different from each other. Further, the precise means through which an app store develops from a ‘stage’ to a ‘walled garden’ may be very different as well. For example, while the Apple App Store has a pre-approval mechanism for apps, the Google Play Store uses an automated threat protection service to safeguard its store. The legal responsibilities which should flow from adopting these varied mechanisms may be very different, and a sophisticated regulatory framework should be able to identify and impose these responsibilities in light of what the platform actually does. This is true at a more general level for all platforms as well.

This discussion points to the need for developing a functional approach which can effectively help the law navigate and apply to digital contexts, including specialised contexts such as app stores. Adopting such an approach may require regulation to rely less on broad descriptors or categorisations of entities in digital contexts and focus more precisely on the design of an app store or a platform and the functions that it actually performs.

Way forward

- Google’s decision to defer the enforcement of changes to its Play Store rules in India points to a resistance to the ‘walled garden’ approach of conceptualising app stores. The way in which this issue plays out may be determinative of whether a ‘walled garden’ approach sustains in the future, or whether pressure from third-party developers will engender a move towards more open mobile environments. Competition law analysis and measures may be essential to ensure that this interaction can play out in a way which is free from market failures.

- The different roles of app stores – as ‘walled gardens’, ‘stages’ and ‘utilities’ – must collectively be considered in any regulatory approach adopted towards regulating app stores. Especially for digital platforms whose role as a ‘stage’ has to be reconciled with the means through which they maintain their ‘walled gardens’, any such approach should be capable of identifying the responsibilities of a platform considering the functions that it actually performs. This may require the adoption of more experimental methods of categorising app stores and digital platforms – which is outlined in further detail in this report by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

Views are personal.