Unpacking Measures by the Indian Government to Tax the Digital Economy

Global consensus required for greater effectiveness

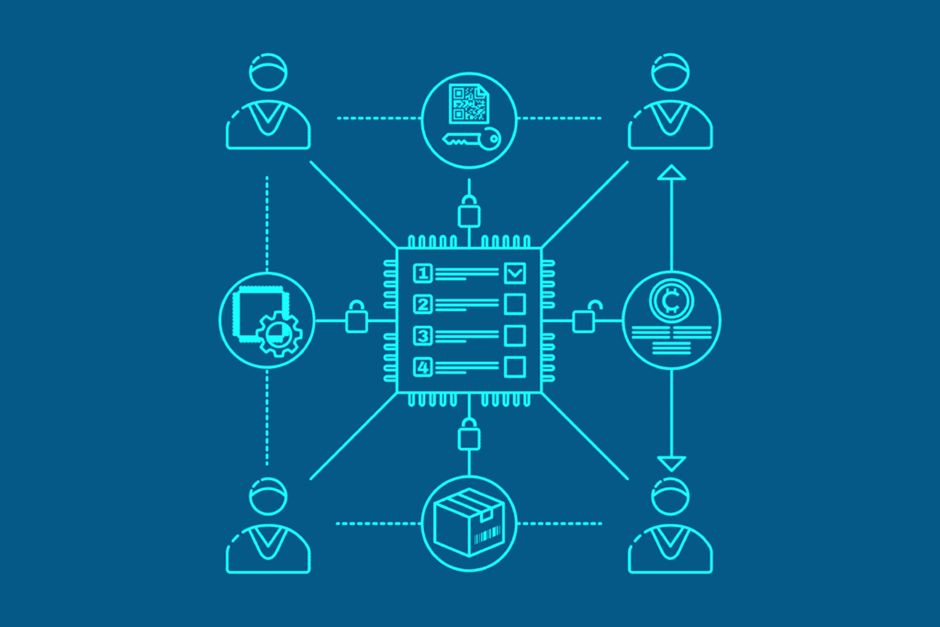

With the advent of technology, there has been a revolutionary growth in the service sector and an elimination of brick and mortar businesses. The existence of physical presence for delivering goods or rendering services is no longer a necessary requirement.

Given this rapid shift, many tax policies designed for brick and mortar businesses have now become obsolete and do not adequately cater to the digital economy. For instance, the international taxation framework taxes the business income of a company in a jurisdiction only if the company has a physical presence therein. The current global framework ignores technological developments that allow companies to cater to markets remotely.

However, the fast-paced development of India’s digital economy has led to a shift in the mindset of tax policymakers from a brick and mortar business to a digital economy. Measures taken by the Indian government recently (as explained below), as well as other schemes and policies, such as the e-commerce policy and the Data Protection Bill introduced to regulate the digital economy, show that India has been an active participant in developing a framework to tax its digital economy.

Early measures adopted by the Indian government (1976)

In 1976, the Indian government incorporated a provision to tax fee for technical, managerial and consultancy services received in India even in cases where there was no physical presence of the organisation in the country.

Around the same time, India also decided to adopt a provision of the UN Model Tax Convention that considered employees or personnel to be deemed to have a physical presence if they were engaged in furnishing services in India for more than 183 days in a 12-month period.

The tax treatment for these two cases was different. This shows that Indian policymakers had recognised early on that services, since they can be delivered remotely, must be treated differently from goods.

Need for better implementation of equalisation levy (2016)

Even though India took early steps to be at the forefront to tax the digital economy, there remains uncertainty around implementation of measures such as the equalisation levy introduced by the government in 2016.

Equalisation levy is a tax imposed at the rate of 6% on gross payments received by non-residents rendering a specified service (currently limited to online advertisement) to an Indian resident. While it was initially limited to online advertisement only, recently the scope has been widened to also include non-resident e-commerce operators involved in online sale of goods or services.

After the old indirect tax regime was changed to the Goods and Service Tax regime through a constitutional amendment in 2017, there has been lack of clarity around how the Centre imposes the equalisation levy and apportions the fund collected through the levy to the state governments.

Thus, even though equalisation levy was introduced with a sound objective, the imposition and administration of such levy functions in a constitutional grey area and can be challenged in a court of law. It has been analysed in greater detail in the report published by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

New provisions in Budget 2020

Recently, a new section 194-O was also inserted in the Income Tax Act, 1961 via the Union Budget 2020 to widen the tax base by bringing participants of e-commerce platforms within the coverage of the Act. This provision imposes a responsibility on the e-commerce operator who is facilitating the sale of goods or provision of services to deduct tax at source of an e-commerce participant who resides in India. This provision was introduced with a view to ensure better tax compliance.

Another policy decision taken by the government to tax the digital economy was to widen the scope of business connection, which is the test for establishing physical presence under domestic law, by introducing the concept of significant economic presence (threshold for which is yet to be fully defined). It had to be put on hold in light of recent developments at the international framework to develop a global consensus based approach to tax the digital economy. Currently, it has been deferred till April, 2022.

Global consensus based approach required to effectively tax the digital economy

A globally agreed upon framework to tax big tech and e-commerce systems is required to effectively tax the digital economy. All unilateral measures taken by any government, including the Indian government, will not have adequate impact in taxing such businesses, and also have the potential to be criticised globally. This was evident when the US imposed trade sanctions on France when the French government decided to impose unilateral measures by introducing Digital Service Tax.

Views are personal.