The Promise of Financial Inclusion

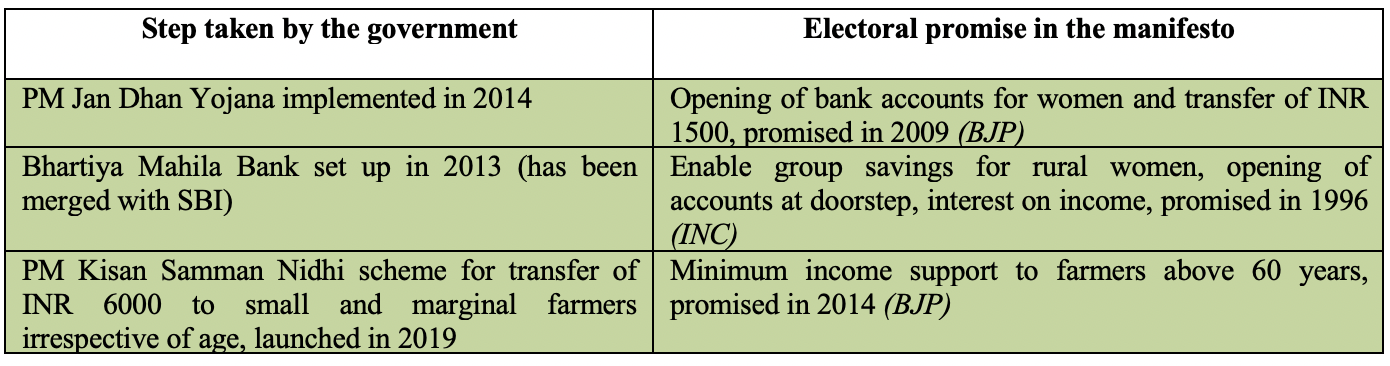

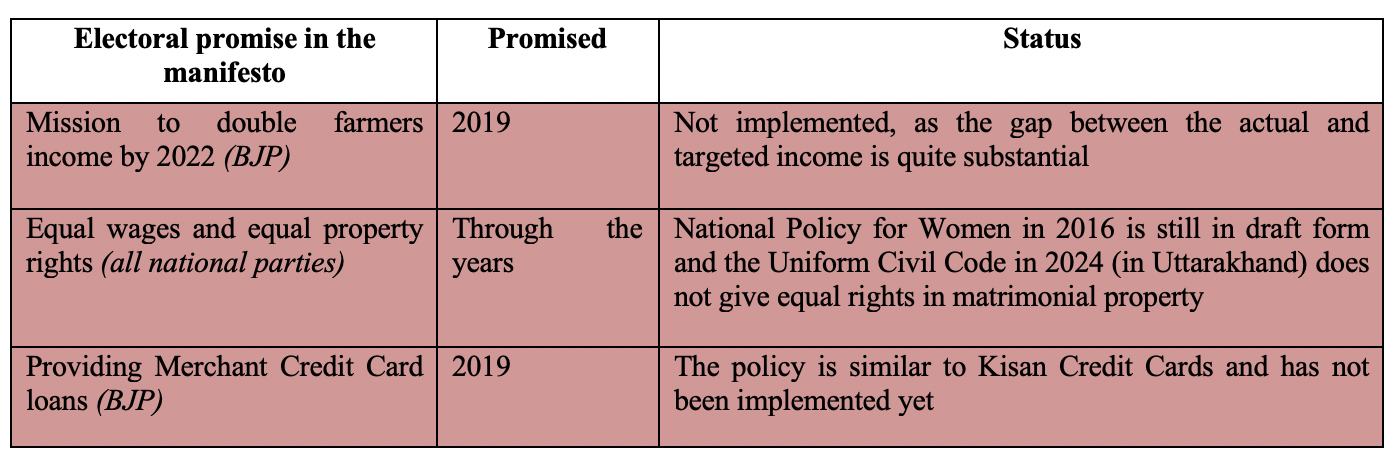

How many of us take the pain of reading a political party’s manifesto? Modi ki Guarantee and Nyaya Patra are more than just manifesto titles as they reveal the vision that politicial parties have for the future, and how they have fared on their past promises. Financial inclusion is fundamental to lead a dignified life and party manifestos contain a wealth of information on the overarching direction being taken by parties in this regard. With the election results round the corner, the manifestos may be the guiding star for the trajectory of financial inclusion measures for the next five years. As time passes, parties tend to re-adjust their goals, so while many commitments are fulfilled, some are left behind. Here are some major financial inclusion steps taken by politicial parties that can be traced back to manifestos of politicial parties:

How 2024 manifestos fare on financial inclusion?

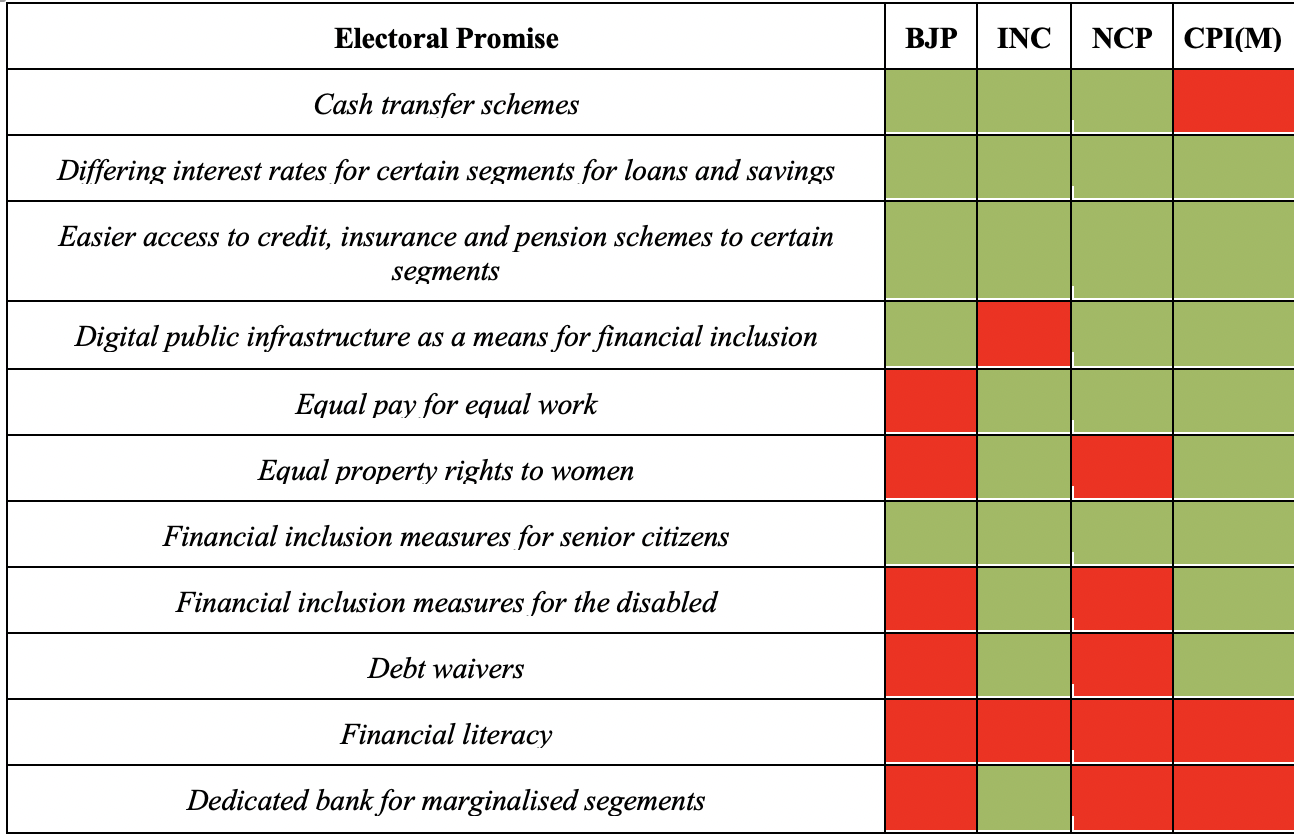

Historically, the measures promised by BJP touched upon debt waivers (1989, 2009), implementation of equal pay for equal work and subjecting all national policies to a gender analysis (1996). The promise to give equal rights to women in matrimonial property and wealth dates back to 1984, and was subsumed within the Uniform Civil Code in 1996. BJP also promised setting up an All Women Mobile Bank and creating women-MSME clusters to streamline benefits (2014). In 2024, these promises, which remain unfulfilled to a large extent, took a backseat to focus more on the usual promises of easier credit, cash transfers and insurance and on using technology for financial inclusion. For the latter, it promises digital rollout of social security schemes relating to insurance, increasing use of UPI by senior citizens and strengthening digital public infrastructure in agriculture. It appears that over the years, as the government establishes itself more firmly, the promises gear more towards digitialisation and guaranteeing handouts, rather than implementation of rights. Further, promises for certain segments such as disabled persons have been diluted.

In contrast, the INC manifesto focuses on rights based measures of equal pay for equal work, equal rights for women in family law matters including property, and making a law for social security measures for gig workers and unorganised workers. At the same time, it also promises cash transfer of INR 1 Lakh to the oldest woman in the family, and a one-time debt waiver for education loans, other than making them interest free. However, it lets go of its 2019 promise for karz maafi for farmers as well as a kisan budget, and instead promises a legal backing to MSP. INC’s promises for financial inclusion traverse a broader range focusing on bringing about justice or nyaaya, while focus on technology or digital infrastructure which are crucial for inclusion is missing.

The NCP and CPI(M) manifestos make a decent attempt to go beyond the bouquet of conventional promises. For instance, NCP promises measures such as mandating gender budgeting for all ministries, use of gender-disaggregated data for gender equality, empowering farmers with green credits for them to participate in the carbon credit economy, and combating pink tax i.e. gender based pricing disparity. CPI(M) promises enacting a law for equal rights in marital and inherited property, disability budgeting in line with gender budgeting, and drastic promises of religion based priority sector lending by banks. While some of these promises are noteworthy, such as use of gender-disaggregated data and use of green credits for farmers’ financial inclusion, their implementation seems far from reality given the current political scenario.

What more can be done

Some measures for financial inclusion are so fundamental, that they should ideally find place in the manifesto of all parties. Some examples are:

Early financial literacy

Financial literacy is a fundamental life skill. While ‘adult literacy’ as a concept finds place in a manifesto or two, ‘financial literacy’, and that too as a part of early years education is missing. Early formal financial education equips individuals to navigate diverse financial landscapes, attach importance to financial habits of saving and building assets and ultimately becoming financially independent. This is especially important for girls, from a young age, to disrupt the never ending cycle of financial dependence.

Grievance redressal mechanisms

The proliferation of digital financial services in contemporary India has led to an escalation of financial frauds, from rudimentary UPI scams to intricate phishing scams, identity theft, amongst others. Despite existing mechanisms to address such frauds, the policy on digital financial frauds in India is struggling to keep up with the rapidly changing landscape of scams, leaving consumers unsure of how to seek help. While promising digital financial inclusion, what is equally important is promising and implementing grievance redressal mechanisms for financial frauds, which are accessable, user-friendly and effective.

Designing suitable financial products

Saving and investing are financial habits, which go a long way in deepening financial inclusion. A one-size-fits-all approach in designing financial products and services is flawed, as the financial needs of different segments of the society differ. Here, the role of financial service providers and the use of gender-disaggregated data in designing financial products gains prominence. Unfortunately, this is sparsely reflected in the manifestos. As men and women save, invest, and spend differently, government’s nudge towards designing suitable financial products and services is imperative for more meaningful financial inclusion.

*The authors of this piece would like to thank Gurmehar Singh Bedi, National Law University, Jodhpur.