A Survey of Advocates Practicing Before the High Courts

The first ever detailed survey of advocates practising before High Courts

Summary: The report presents the results of a survey of 2800 advocates practicing at the High Courts at Allahabad, Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi, Gujarat, Kerala, Madras and Patna.

Background

Historically, the legal profession in India has been paid little attention to in the public discourse on judicial reforms. Despite being one of the oldest professions in India, it also happens to be one of the most understudied, so much so that there is no authentic source to even verify the number of advocates in India. Ironically, one of the main sources of empirical studies on the Indian legal profession are the papers published by American scholars from the law and society movement, which studied the formal legal system created by the British. Much has changed since then, and there has been no systematic attempt at studying Indian lawyers, especially those practicing before various courts in the country.

To plug this gap, JALDI (Justice, Access and Lowering Delays in India) project at Vidhi commissioned a survey of 2800 advocates practicing before eight High Courts in the country. The survey, the first of its kind in India, throws light on the practicing advocate’s perception about the institution of judiciary, their relationship with the Bar Councils, and informs us about their professional standing in terms of income levels and career prospects.

Methodology

For the survey, eight High Courts were chosen which account for approximately 57% of the total High Court judges in the country. These High Courts were chosen on the basis of the following considerations:

1. The High Courts at Bombay, Calcutta, Madras and Allahabad are amongst the oldest and largest High Courts in the country whose traditions and practices date back to the 19th century;

2. The High Courts at Delhi, Gujarat, Patna and Kerala are located in the same geographical zones as the previous four. This ensures that the survey covered two High Courts in the north, south, east and west of the country making the survey as geographically representative as possible.

Additionally, a pilot survey was carried out at the Delhi High Court to assess the feasibility of the questionnaire. After the pilot was conducted, a feedback session with the enumerators was organised and the questionnaire was revised to accommodate the suggestions. However, only four questions were revised for the final questionnaire. To indicate that the Delhi High Court was the site for the pilot survey, the results from Delhi are distinguished from the rest of the High Courts.

| High Court covered under the survey | Number of advocates surveyed |

| Delhi | 356 |

| Allahabad | 351 |

| Bombay | 358 |

| Calcutta | 356 |

| Gujarat | 355 |

| Kerala | 350 |

| Madras | 400 |

| Patna | 354 |

Key findings

1. Perception of the Higher Judiciary: Advocates interact with judges on a daily basis – this allows them to observe the behaviour and diligence of judges. In this context, we included questions to measure the perceptions of advocates on different aspects of judicial functioning such as probity, competence, impartiality and independence from the government. Additionally, we also asked the advocates about their perception of the collegium system of judicial appointments.

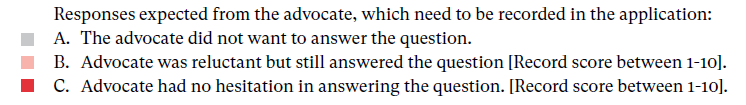

Corruption – The advocates were asked to score their perception of corruption in the higher judiciary between 1 -10, where a score of ten indicated that corruption is well entrenched in the higher judiciary.We found that 107 advocates who chose to answer the question from the Bombay High Court gave it a score of 10; on the other hand, in Gujarat High Court, 115 advocates who chose to answer the question gave it a score of 2-3.

It is also pertinent to note that 266 and 254 advocates at the High Courts of Calcutta and Madras respectively chose to not answer the question at all. In stark contrast, 249 advocates from the Patna High Court had no hesitation in answering the question.(see page 13)

Key for the graph:

Fair hearing – On the issue of getting a fair hearing before judges, we found that 97.19%, 82.87% and 93.22 % of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Calcutta, Delhi and Patna respectively felt that their chance of getting a fair hearing depends on the bench. (see Page 15)

Collegium system – When asked whether the collegium system of appointments should be continued with or replaced with some other mechanism such as the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC),

● 53.63% of surveyed advocates from the Bombay High Court felt that the judiciary should continue with the collegium system in its current form;

● 90.4%,80.34%, 62.82% and 37.04% of surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Patna, Calcutta, Gujarat and Allahabad respectively felt that the collegium system should continue but with greater transparency;

● Pertinently, 64%, 34.25% and 32.58% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Kerala, Madras and Delhi felt that the collegium system should be replaced with NJAC. (see Page 19)

2. Perception of the Bar Council: Under this theme we explored the relationship between advocates and the Bar Council of India (BCI), which is the apex regulatory body of the legal profession. In addition to this, we looked at the effectiveness of the welfare fund, the perception of advocates on the restrictions imposed against advertising, the popularity of the prescribed dress code and the inclination to continue legal education amongst practicing advocates.

With regard to the effectiveness of the Advocates Welfare Fund, 92.4%, 65.7% and 75.4% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Delhi, Madras and Gujarat respectively were not aware of anyone having received financial assistance under the fund. (see page 23)

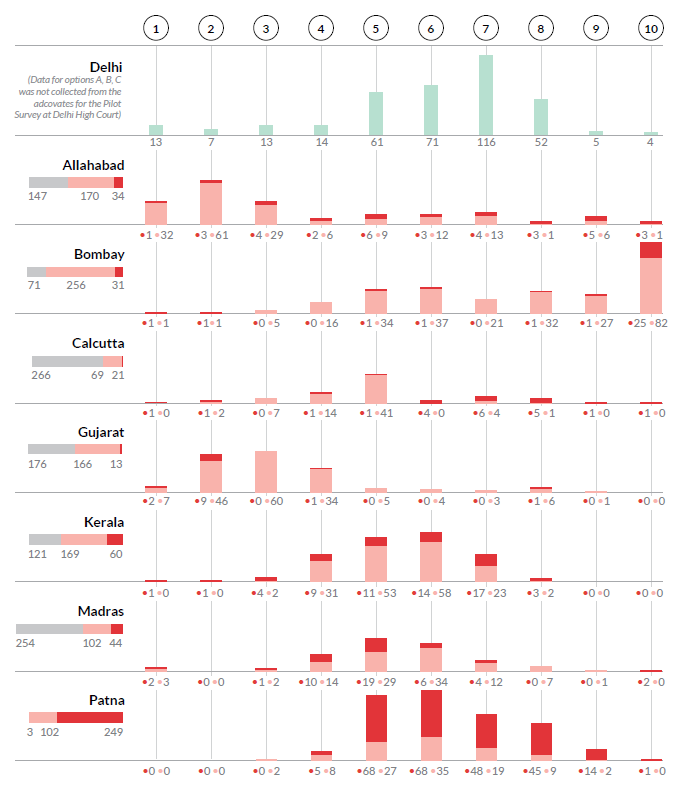

Have you or any other lawyer whom you know, received assistance from the Advocates Welfare Fund that was established by a law in 2001 [The Advocates Welfare Fund, 2001]? [Y/N]

Among other questions on this theme, advocates were asked for their views on the restrictions imposed by the Bar Council of India with regard to advertising their services to potential clients. At present, there is a general prohibition against solicitation of work by advocates with a minor relaxation to create websites that provide basic information including contact details, qualifications and area of practice. The responses reveal that 65.5%, 87.4%, 81.4%, 60.5%, 64.8%, 94.6% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Allahabad, Bombay, Calcutta, Gujarat, Kerala and Patna respectively, were in favour of amending the rules which imposed restrictions on advertising. (see page 24)

3. Perception about the earnings and the practice: The third theme explored perceptions of the earnings of advocates at different stages of their careers, the affordability of law reporters and online legal databases, the effect that caste/religion of the advocates has on their professional life and languages used by High Courts to conduct their proceedings.

As many as 80% of the surveyed advocates from the Delhi High Court believed that lawyers in their first two years of practice earn between Rs. 5000 and Rs. 20000 per month. A lower scale of Rs 2000-Rs 5000 per month was included in the options given to respondents based on the feedback received from the enumerators who conducted the pilot survey at the Delhi High Court.

Consequently, 40% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Allahabad, Bombay, Kerala, Madras and Patna were of the opinion that young lawyers earned between Rs. 2000 and Rs. 5000 per month, during their first two years of practice. (see Page 28)

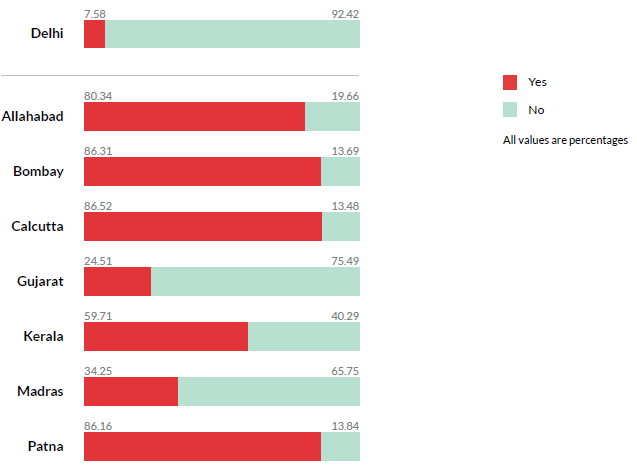

Majority of the advocates surveyed stated that they subscribed to print or online databases of law reports. More than 50% of the surveyed advocates across all High Courts found the subscription fees to these law reports to be affordable.

Additionally, 47%, 67%, 66% and 72% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Bombay, Calcutta, Gujarat and Madras respectively were of the view that English should continue as the language in which the High Court conducts its proceedings. On the other hand, 78%, 54% and 81% of the surveyed advocates at the High Courts of Allahabad, Kerala and Patna respectively thought that they should have the liberty to argue either in English or in their local language. (See Page 34)